Profound changes are occurring on high streets throughout the country. In order for policies aimed at their planning and stewardship to succeed, a greater understanding of how high streets adapt to changing economic conditions and serve their neighbourhoods is needed. Suzanne Hall argues for a multidisciplinary approach in understanding the social and economic particularities of high streets.

Profound changes are occurring on high streets throughout the country. In order for policies aimed at their planning and stewardship to succeed, a greater understanding of how high streets adapt to changing economic conditions and serve their neighbourhoods is needed. Suzanne Hall argues for a multidisciplinary approach in understanding the social and economic particularities of high streets.

Since late 2008, economic crises and legislated cuts have reverberated across Britain, impressing on a daily basis that we live and work in an austere and volatile present. To what extent are small urban entrepreneurs and micro socio-economic networks able to adapt to global economic change? In the context of the high street, I argue for a greater understanding of the social and economic particularities of local worlds if policies aimed at their planning and stewardship are to succeed.

The High Street London report (2010) commissioned by the Mayor’s Office emphasises ‘the local’ role of London’s high streets for a ‘local’ populous, and is representative of recent policy shifts towards recognising small shops and high streets in London within the larger national policy emphasis on Localism. At a national scale, the Mary Portas review on The Future of the High Street points to a public concern regarding the general economic demise of high streets across the UK. However, this legitimate public debate has been served by broad, quantitative analysis, and planning policy would be well served by more detailed understandings of urban high streets and their particular retail practices.

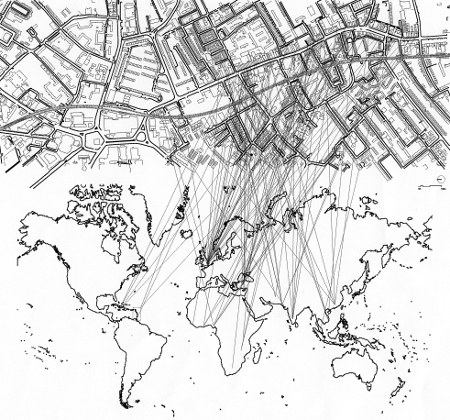

As a street located within the urban margins of London, Walworth Road offers us a particular frame through with which to view adaptation. It has a substantial portion of independent retailers (56 per cent of the total street occupancy) who deliver a range of goods and services. Further, over twenty different countries of origin are represented amongst these independent proprietors, as indicated in mapping of the Walworth Road juxtaposed with a map of the world (see figure 1).

Within the dense accumulation of small shops along the Walworth Road, stories from the independent retailers range from adaptive strategies to ensure business continuity, to the precarious reality of change as associated with higher rents and rates and increasing competition from the large-scale, affiliated retailers. The small independent retailers develop mercantile and social strategies to adapt to large-scale economic change and, amongst the 44 per cent of the independent shops who had been on the Walworth Road for more than 10 years, the proprietor-customer relationship or the notion of ‘personal service’ was strongly emphasised.

However, larger changes in the broader Walworth neighbourhood are imminent. A mixture of new private and social housing developments are being built in the area as part of the Elephant and Castle, Heygate Estate and Aylesbury Estate regeneration processes. Although the pace of regeneration has been held in check by the economic crisis, new, potentially more affluent residents, coupled with the dramatic growth in demand for retail space across London, is likely to challenge the Walworth Road’s historic capacity for small-scale adaptation. Does this matter? Should high street adaptation respond in an unfettered manner, as it historically has, to market forces? Or is there room for less affluent, more diverse patterns of life and livelihoods on the street within the prospects of economic and urban change?

Planning protection could take the form of the overarching coordination of centres or streets as a whole, through a guiding framework and/or operational stewardship mechanism. The purpose of coordination is to understand the role of the town centre/ high street in its local area context and to protect and enhance the combined socio-economic space of the street as a whole. But unless this coordination is mindful of the cultural role of the street, it is likely that dominant economic measures of value will prevail over social and local ones. More predictable store formats and brands may well be regarded as more viable than independent or ethnic shops, as highlighted by the New Economics Foundation in their Clone Town Britain report (2004).

The idea of the coordination of the economic and cultural interrelationship of the street is increasingly well developed in affluent or upmarket streets through a privatised stewardship mechanism of property estate managers that seek to generate high profit yields, but also to promote the unique cultural space of the street closely tied to retail mix. The revitalisation of the Marleybone High Street, as articulated by Simon Baynham, is a good example of this.

In principle, public stewardship is the coordination of expertise together with a view of the whole. It is potentially a vehicle for transmitting local knowledge alongside adherence to national policy, and if, like registered social housing landlords, it is associated with the local authority it is legitimately local and accountable. Unlike a private model, it is not resourced through profit, and the use and allocation of scare public resources would need to focus on the collective investment of managing the street as a whole.

It is debateable whether the planning legislation in Britain has served the independent retailer well, let alone the ethnic minority retailer. Small independent shops often operate with a far more localised knowledge base, and their political representation at the scales of national and local scale is limited. This brings into question the potential impact of the Localism Bill on high street locales.

If ‘Localism’ is to have political and economic significance for the diverse citizens who occupy and use London’s diverse high streets, then a focus on its cultural, social and economic interrelationships, as a key way of comprehending ‘the local’ is necessary. We need to recognise how varied high streets and town centres are used and occupied differently. This will require getting down on to the street to conduct both quantitative and qualitative studies of how small shops do or don’t adapt to large-scale impacts of change.

What is further needed is more interdisciplinary research in understanding the economic life of local worlds in the context of global change. Alternative measures of value such as ethnic and cultural diversity and retail longevity or duration are intricacies that require political recognition and policy articulation in terms of the high street as a cultural and particular condition. A greater integration of spatial, social and economic understandings of urban high streets would further serve the evaluation, planning and day-to-day stewardship of high streets.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the author

Suzanne Hall – LSE Sociology

Suzanne Hall is an urban ethnographer, and has practised as an architect and urban designer in South Africa. She teaches primarily in the MSc City Design and Social Science programme and is a Research Fellow in Urban Culture and Design at LSE Cities. Her research and teaching interests are foregrounded in local expressions of global urbanisation, particularly social and spatial forms of inclusion and exclusion, urban multiculture, the design of the city, and ethnography and visual methods. She is a recipient of the LSE’s Robert McKenzie Prize for outstanding Ph.D. research (2010).