Ben Goodair and Aaron Reeves empirically evaluate the impact of outsourced spending to private providers, following the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, on treatable mortality rates and the quality of health-care services in England. They find that in areas with increases in outsourcing there are more deaths of people with treatable conditions.

Ben Goodair and Aaron Reeves empirically evaluate the impact of outsourced spending to private providers, following the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, on treatable mortality rates and the quality of health-care services in England. They find that in areas with increases in outsourcing there are more deaths of people with treatable conditions.

NHS patients in England receive care which is free at the point of need but, increasingly, that care is delivered by private companies rather than the NHS itself: by the beginning of the pandemic, companies like Spire, Virgin, and Circle were providing over 10% of the treatments delivered to NHS patients. And between 2013 and 2020, NHS commissioners spent over £11.5bn on services provided by for-profit companies. Research we have conducted details the increases in privatisation and finds that it corresponds with a worse quality of healthcare.

Is the NHS being privatised?

The outsourcing of services to independent providers has long been a major issue for policymakers, health workers, unions, and patients. Fears exist that the principles of equity which are integral to a National Health Service are not mirrored in the private sector, meaning that inviting the profit motive into service provision will result in inequitable outcomes and worse care for patients.

But others have rejected these fears, suggesting that any tangible form of NHS privatisation is a construct of the imagination and used as a political football. In the House of Commons this year, the Health Secretary at the time, Sajid Javid commented: ‘Whenever the NHS is subject to change, it is tempting for some, who should actually know better, to claim that it is the beginning of the end of public provision. We know that that is complete nonsense, and they know it is nonsense, but they say it anyway’.

A variation of this argument is that significant privatisation has not been observed with the data which is available, and that granular analysis of individual contracts has not been possible. Indeed, procurement of health services is fragmented between regional commissioners and individual providers making analysis difficult, and the reported accounts data contains almost no information on the recipients of NHS expenditure.

This issue has now been resolved by research which has published data of all available expenditure files (which are in a usable format) posted online by NHS organisations in one clean and accessible place. This means we can now see how much money suppliers receive and therefore measure how much NHS organisations have been outsourcing to for-profit companies.

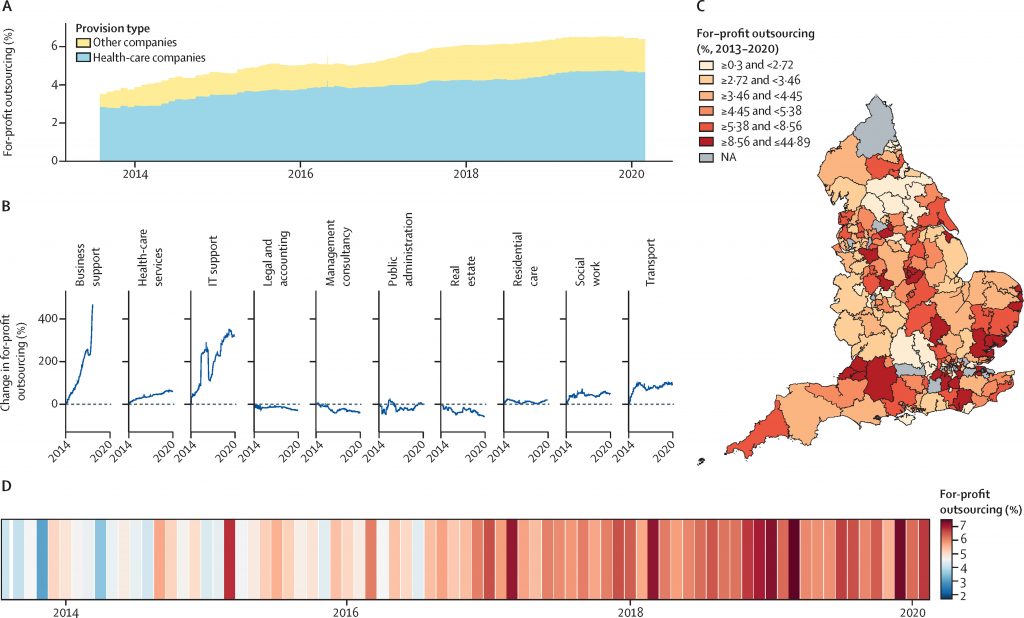

Figure 1 shows results from our recently published research that NHS privatisation, through outsourcing of services to for-profit companies, has been consistently increasing since 2013, but that this varies tremendously between different regional commissioners.

Figure 1: Levels of clinical commissioning groups outsourcing to for-profit organisations from 2013 to 2020.

NHS privatisation has been incremental but substantial – the observed increases representing additional billions of pounds spent on for-profit provision of services. Most of this expenditure is spent on healthcare companies and this type of outsourcing is also increasing steadily.

However, despite the data now being publicly available and the trends clear to see, it appears the debate might not end. In a statement responding to our findings the Department of Health and Social Care claim ‘there has been essentially no proportional increase in NHS spending with non-NHS providers over the last decade’. We arrive at a different conclusion, this new data can help resolve the debate as to whether the NHS is being privatised – and it evidences a tangible ‘creeping privatisation’ of NHS services.

Impacts on Quality of Care

But what does this mean for the quality of care? Analysis we conducted uses this new data and finds that in regions where there are rising levels privatisation, patients overall are getting poorer care. In fact, we find that what gets worse is treatable mortality – that is, conditions ranging from diseases of the digestive system to some types of cancer, where death can be avoided by giving the patient the right treatment at the right time.

Our research shows that in areas with increases in outsourcing of healthcare there are more deaths of people with these kinds of treatable conditions. These are deaths aggregated across all health providers – NHS and for-profit companies so we cannot conclude that one type of provider offers better or worse care than the other. Previous research has demonstrated how hard it is to compare treatment outcomes in different providers because the types of patients cared for by the two types of provider are different with the outsourced companies tending to take the least complex cases.

We run many sensitivity checks to make sure our finding is robust, and our interpretations are sensible. For example, we run all our models again but only including expenditure which goes to healthcare companies (removing any spending on facilities management, IT support etc.). We find the same results. We also control for the total expenditure of Clinical Commissioning Groups to ensure that our result is not confounded by some financial strain resulting in higher outsourcers simply spending less in the public sector and having worse outcomes in this way.

The outsourcing of services to for-profit companies is corresponding with worse healthcare. Our research has not aimed to find the ‘hows’ and ‘whys’, just whether outsourcing is, on aggregate, improving or worsening healthcare quality.

The consequence for policy reform

A key justification for our research looking at the aggregate impacts of outsourcing – rather than performance of a particular service or provider – is that the policy context of NHS marketisation has encouraged outsourcing to the private sector, blind to these kinds of nuance.

Opening NHS contracts to an external market has been a conscious policy decision, one which was furthered in 2012 with the introduction of the Health and Social Care Act. These reforms aimed to stimulate competition between for-profit and public providers in the belief that this has an aggregate beneficial impact on public service provision. However, these reforms enable the gradual outsourcing of services to the private sector, which we find are associated with an aggregate decline in quality of care.

Our research gives the first insight into the consequences of outsourcing since the controversial 2012 Health and Social Care Act. Overall levels of outsourcing in England increased consistently from 2013 when the act was introduced, rising from less than 4% to more than 6% of total regional health board spend by 2020. This was something that campaigners warned would happen at the time.

Recently, another major reform has been introduced to the NHS commissioning landscape. Once again, campaigners are worried about the lack of protection for NHS providers in the healthcare market. Our evidence suggests that, without a change in direction, the levels of for-profit provision commissioned by the new bodies will continue to rise, and that this may continue to correspond with an average deterioration in the quality of care.

_____________________

Ben Goodair Doctoral researcher in the Department of Social Policy and Intervention at the University of Oxford.

Ben Goodair Doctoral researcher in the Department of Social Policy and Intervention at the University of Oxford.

Aaron Reeves is Associate Professor in the Department of Social Policy and Intervention at the University of Oxford.

Aaron Reeves is Associate Professor in the Department of Social Policy and Intervention at the University of Oxford.

Photo by jesse orrico on Unsplash.