The ‘broken windows’ theory has dominated policy debates over how to deal with crime and disorder for more than three decades, but few have examined how disorder influences political engagement. Using data from Chicago, Jamila Michener finds that people’s perceptions of disorder are a powerful influence on their likelihood to engage politically, such as speaking to a politician or attending a community meeting. She argues that the way people interpret the ‘broken windows’ of their neighborhoods can be a critical determinant of how grassroots politics develop.

The ‘broken windows’ theory has dominated policy debates over how to deal with crime and disorder for more than three decades, but few have examined how disorder influences political engagement. Using data from Chicago, Jamila Michener finds that people’s perceptions of disorder are a powerful influence on their likelihood to engage politically, such as speaking to a politician or attending a community meeting. She argues that the way people interpret the ‘broken windows’ of their neighborhoods can be a critical determinant of how grassroots politics develop.

This article was originally published on LSE’s USApp blog.

Graffiti, litter, abandoned and boarded up buildings: many of us know a “bad” neighborhood when we see it. According to the popular theory of “broken windows,” these directly observable material conditions have an influence on the ways people respond to their local environment. Proponents of this theory argue that minor but visible signs of neighborhood disorder lead to more serious criminal infractions. This controversial claim has motivated policy and sparked enduring debates over whether and how neighborhood disorder affects crime. Social scientists have drawn on the core intuition of broken windows theory (that salient physical and social neighborhood conditions impact behavior) to consider the economic and even psychological consequences of disorder. Yet, scholars and policymakers have remained silent about its political ramifications. This is especially problematic because the possibility of transforming blighted neighborhoods is at least partially rooted in local political engagement. Without knowing how such engagement is impacted by disorder, we cannot adequately map the participatory pathways that might reinvigorate “bad” neighborhoods.

To assess the role that neighborhood disorder plays in shaping local participation we need to understand at least two things: 1) the concrete conditions of neighborhoods and 2) how people interpret those conditions. The first involves the material realities that residents confront when they walk out of the door everyday. These experiences can make a profound impression. Anyone who has driven through, walked by or lived amidst urban decay understands why. Some neighborhoods inspire comfort while others rouse fear and even loathing. Much of this has to do with the objective physical setting. Yet, there is more to it than that. People have unique outlooks on “objective” circumstances and divergent perceptions of one’s environment can mean that the same “reality” has variable effects across and within neighborhoods.

Keeping this in mind, I designed a study to evaluate the relationship between neighborhood disorder and political participation, taking care to account for both tangible markers of disorder and subjective perceptions of it. Utilizing exceptionally rich data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, I found that while objective conditions are politically consequential, these perceptions are a more powerful and consistent mechanism through which neighborhood disorder affects citizen engagement.

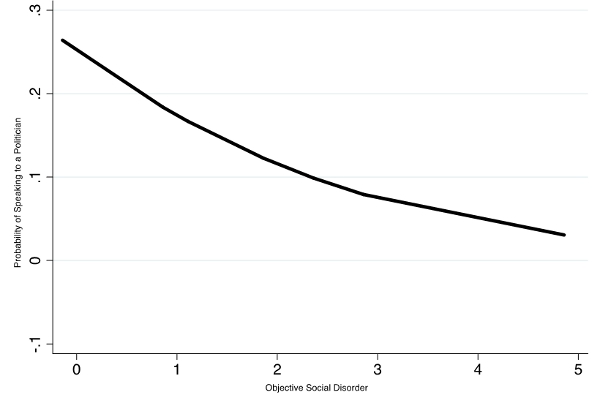

As shown in Figure 1, increasing levels of objective social disorder (this includes things like adults loitering in the streets, drugs being sold openly, prostitution and public alcohol consumption-all of which were measured through systematic observation techniques) are associated with decreased likelihood of local residents reaching out to political officials (this effect was as high as 23 percentage points).

Figure 1 – Probability of Speaking to a politician by objective social disorder

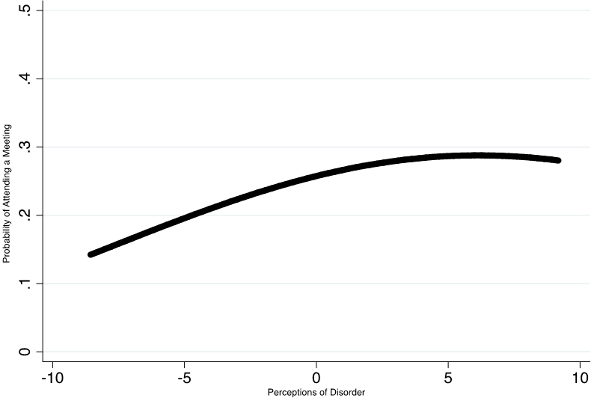

While strong, the relationship between participation and objective disorder is just the tip of the iceberg. Subjective interpretations of the conditions connected to disorder are also critical and extend to even more forms of participatory behavior. For example, as conveyed in Figure 2, neighborhood residents who report perceiving the least disorder in their neighborhoods are 14 percentage points less likely to attend a meeting to discuss neighborhood problems than those who report perceiving the most disorder (even after controlling for the concrete material context and a host of other factors).

Figure 2 – Probability of attending a meeting by perceptions of disorder

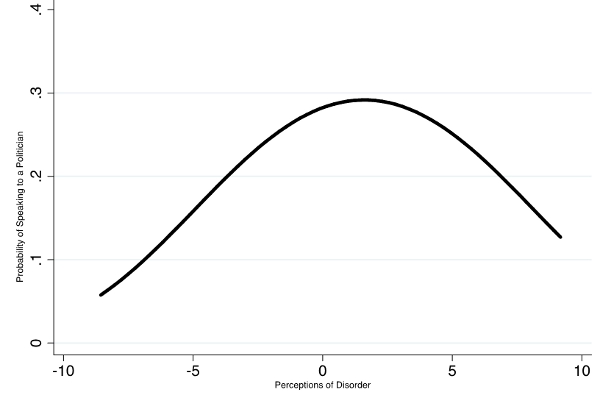

Further still, the role of perceptions grows more complex as we consider different modes of participation. As shown in figure 3, the impact of perceptions is not always linear. Neighborhood residents with average perceptions of disorder are 22 percentage points more likely to speak to a politician than those with the most negative perceptions and 15 percentage points more likely than those with the most positive perceptions. Substantively, this means that community members on the extremes- those with a very bad or very good perspective towards their environment- are less likely to participate via formal contact with an elected official than those who fall in the middle. Since contact with politicians is a relatively high cost and often solitary mode of participation, it makes sense that the proclivity for engaging in this way is more susceptible to being swayed.

Figure 3 – Probability of speaking to a politician by perceptions of disorder

Ultimately, even holding constant objective contextual features, the lenses through which community residents interpret things like “broken windows” are critical determinants of grassroots politics. This is not just a nifty scholarly finding, it bears directly upon the factors that policymakers must consider as they determine the best practices for promoting strong neighborhoods and urban renewal. Turning to perceptions when evaluating policy responses to disorder requires that we reflect on the participatory consequences of things like aggressive policing, gentrification and demolition projects – deliberating not only about the tangible results of such policies but also about the ways they shape residents’ interpretations of their environments.

A recent study by political scientists Vesla Weaver and Amy Lerman offers a timely and significant example of how public policy is implicated in shaping the democratic life of disadvantaged communities. Lerman and Weaver find that the concentration and nature of police stops in New York City impacts levels of citizen engagement (i.e. the frequency with which citizens make 311 calls). Most notably, they show that police stops involving invasive searches or the use of force have a “chilling effect on neighborhood level outreach to local government.” One reason for this is that antagonistic relations with the police taint citizens’ views of government and law enforcement. In this way, stop-and-frisk tactics highlight the perceptions-to-participation link and demonstrate why policy must be evaluated with an eye toward repercussions for community participation. This means that the attitudes and ideas of ordinary neighborhood residents are too vital to be neglected- particularly in the most disadvantaged areas. It is these blighted places that need the most renewal and if they are to be regenerated from the bottom up, political elites can no longer afford to sanction policies that unwittingly stifle a democratically driven public life.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Neighborhood Disorder and Local Participation: Examining the Political Relevance of ‘‘Broken Windows’’’ which appears in the December 2013 issue of Political Behavior.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the British Politics and Policy blog or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Jamila Michener – Cornell University

Jamila Michener – Cornell University

Jamila Michener is an Assistant professor in the department of Government at Cornell University. Her research focuses on poverty and racial inequality in American politics. Her current work explores the conditions under which disadvantaged groups engage in the political process, and the role of the state in shaping the political and economic trajectories of marginalized communities.