Does trust in politics and politicians matter? Using a meta-analysis of 58 published studies, Daniel Devine shows that trust is related to a diverse range of political outcomes such as whom people vote for, whether they vote at all, their support for government spending, and preferred levels of immigration.

Does trust in politics and politicians matter? Using a meta-analysis of 58 published studies, Daniel Devine shows that trust is related to a diverse range of political outcomes such as whom people vote for, whether they vote at all, their support for government spending, and preferred levels of immigration.

The British public think a lack of trust in politicians and government is one of the top five issues facing the country. Politicians have responded. At the start of 2022, Labour leader Keir Starmer promised to restore trust in government – just as Boris Johnson did after winning the 2019 General Election. Academics, such as TrustGov, and think tanks, such as IPPR and Demos, have projects to understand trust. And this concern is not just in the UK: the United Nations Secretary-General bemoaned the ‘trust deficit’ around the world, and the OECD have a large agenda to improve trust in government.

These concerns aren’t new. Trust in government has been written about since at least the 1960s with the widespread use of public polling; a book titled ‘Crisis of Democracy’, published in 1975, blamed trust in part for this apparent crisis. This implies people think trust is important. And there are definitely normative reasons why: trust has long been seen as a condition for legitimate government. That the public think their government can be trusted with their money and security, to be left to develop and implement policy, feels intuitively fundamental; perhaps even more so that the extension of the state, such as local councils and law enforcement, can be trusted. But the concern with trust extends further than that. Lack of trust is touted as one of the (many) causes of populism; for polarisation and incapacitation of the United States; and much else, from the decision to vote at all or instead protest, preferences over policy such as immigration and redistribution, and vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is surprising in all of this is that the evidence that trust matters for these outcomes is not clear at all. It is sparse relative to the evidence on the trends and determinants of trust, for instance; there is also no consensus on either its direction (whether trust increases or decreases voter turnout) or magnitude (how much it increases or decreases it by).

To see whether these important outcomes really are related to trust, I conducted a meta-analysis of existing research. A meta-analysis systematically brings together all research within a specified search, and then quantitatively summarises it to produce an estimate of just how much specific outcomes are related to trust. This means it is not just relying on one study, which can be unreliable, but all relevant studies returned by the search.

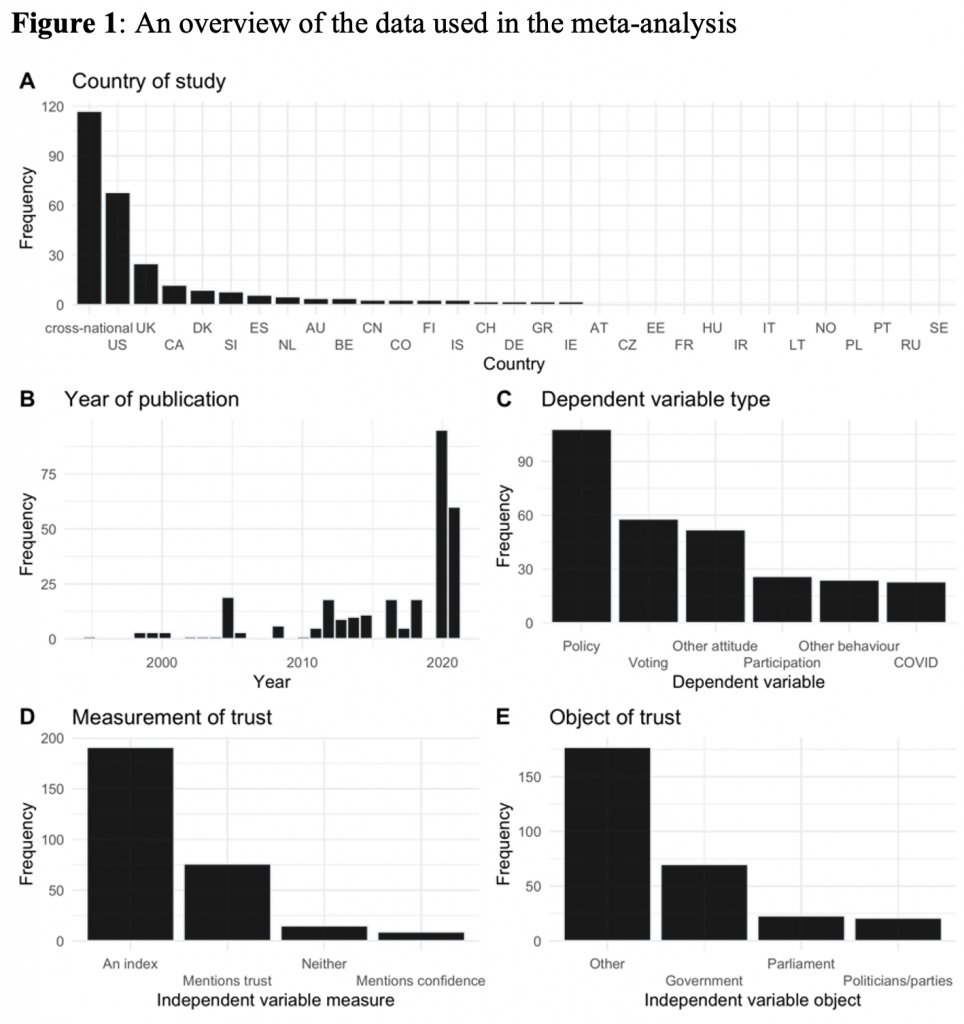

Starting with 9,135 initial texts returned by searching academic databases and ten political science journals, I screened them down based on specified criteria to 58 texts that were included in the final analysis. I coded all these texts, taking information such as the country of study, types of questions used to measure trust, and statistical data. Some of the papers were also coded by another researcher to ensure my decisions were correct. This led to 291 different estimates for how trust was related to outcomes from voting turnout, voting decisions, to preferences over government spending, immigration, and vaccine hesitancy.

An overview of the data is in Figure 1. This shows that most of the research was conducted after 2010 (likely due to the interest in trust after the economic crisis), and a plurality of it relies on cross-national data. Of single-country studies, by far the most common are studies on the United States and United Kingdom. The survey also shows that a plurality of studies are on trust and policy preferences, with voting (such as turnout and party choice) in a distant second.

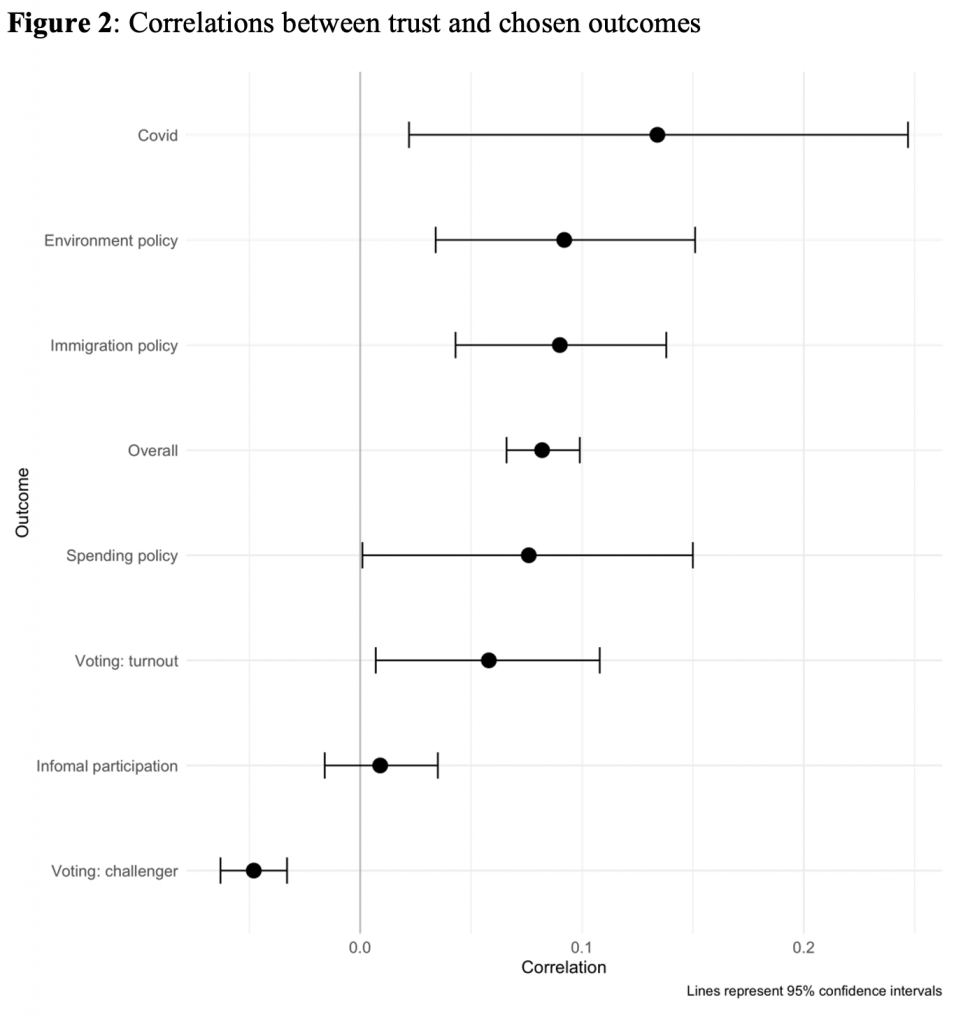

What do these studies find? This is shown in Figure 2 for eight outcomes. These outcomes were chosen since they have more than ten estimates; fewer than that (or fewer studies from which they’re from) reduce the use and reliability of meta-analysis. The ‘overall’ category pools all 291 estimates and 58 estimates and ignores whether the effect is negative or positive, indicating the total size of the effect of trust, averaged across all outcomes.

The evidence shows that trust does have a reasonable correlation with a range of outcomes: preferences over the environment, levels of immigration, spending, turnout, and whether people vote for ‘challenger’ parties (those out of the mainstream). The only area where the results indicate trust does not have an effect is on informal political participation, such as protesting. The largest effect is for outcomes related to COVID-19 – this includes things like vaccine hesitancy and belief in conspiracy theories.

In practice, what this means is that those who are trusting are more likely to turn out to vote, advocate for higher government spending, believe in and support policies aimed at mitigating climate change, and less likely to vote for challenger parties. These are all features of mainstream social democratic or progressive politics, which has led to some academics arguing that trust is relevant for understanding the global decline of social democracy. Similarly, those who trust are more likely to ‘believe in’ COVID-19 and policies aimed to mitigate against it.

It is important to note that most of these relationships are quite weak. The generally accepted benchmarks are that correlations less than plus or minus 0.3 are weak. But most of these correlations are when controlling for other factors like education, allegiance to political parties, age, and other political attitudes. That trust has any explanatory power left is impressive in itself. And other meta-analyses in the social sciences indicate similar correlations, such as a correlation of 0.09 to 0.13 between terrorism and political attitudes.

Overall, the evidence so far suggests trust in politics and political institutions is important in explaining a range of other political outcomes. This might be comforting for researchers who study trust. But it should be concerning in light of the long-term decline in trust in the UK and other countries (though others have not seen declines in trust). If these results are correct and causal, the long-term decline in trust will have long-term consequences for politics.

__________________

Note: the above draws on a working paper, available here.

Daniel Devine is a Fellow in Politics at St Hilda’s College, University of Oxford. He works on political trust, voting and political preferences in Europe.

Daniel Devine is a Fellow in Politics at St Hilda’s College, University of Oxford. He works on political trust, voting and political preferences in Europe.

Featured image credit: by Bernard Hermant on Unsplash.