Why has Britain’s welfare system been reformed so radically and why, until recently, did the public enthusiastically endorse such changes? Tom O’Grady traces the evolution of British welfare policy, politics, discourse, and public opinion since the 1980s, and argues that since the 1990s, a long-term change in discourse from both politicians and the media caused the public to turn against welfare by 2010. That, combined with the financial crisis, left the system uniquely vulnerable to cuts.

Why has Britain’s welfare system been reformed so radically and why, until recently, did the public enthusiastically endorse such changes? Tom O’Grady traces the evolution of British welfare policy, politics, discourse, and public opinion since the 1980s, and argues that since the 1990s, a long-term change in discourse from both politicians and the media caused the public to turn against welfare by 2010. That, combined with the financial crisis, left the system uniquely vulnerable to cuts.

Since 2010, the UK has drastically cut benefits for unemployment, disability, housing and poverty relief. This was accompanied by the creation of Universal Credit, combining all previous benefits into one single payment. These reforms have been extremely regressive. Data from the IFS shows that families in the bottom earnings decile lost 20% of their net income on average from 2010-19 due to the changes, an extraordinary figure that is even starker in comparison to pensioners, whose incomes were protected across the board. Conditions for the receipt of benefits have also increased. Claimants are now subject to greater monitoring of their efforts to find new work, with stronger sanctioning for those failing to comply. Extensive research has documented the effects of these changes on homelessness, indebtedness, mental ill health, food bank use and absolute poverty. My book asks a different question: why have such extreme changes taken place?

It is partly a story of austerity. Universal Credit was originally designed to lift over one million families out of poverty. But over the post-2010 period, the Treasury demanded cuts to other welfare programmes in return for implementing it, and then enforced cuts to the new programme too that greatly compromised its initial design. This only begs the question, though, of why welfare bore the brunt of cuts whilst other areas like pensions, health, and international development did not – and why such an extreme set of cuts and reforms was politically feasible in the first place.

To help answer this, in the book I compare the UK to other European countries that have also enacted welfare-to-work reforms such as Denmark and Germany. The post-2010 changes to British welfare have no parallel in those places. Their welfare reforms stalled after the financial crisis. None have enacted cuts with such regressive consequences, nor do they police the lives of welfare recipients so intensively. Britain is exceptional; it has diverged from the European norm.

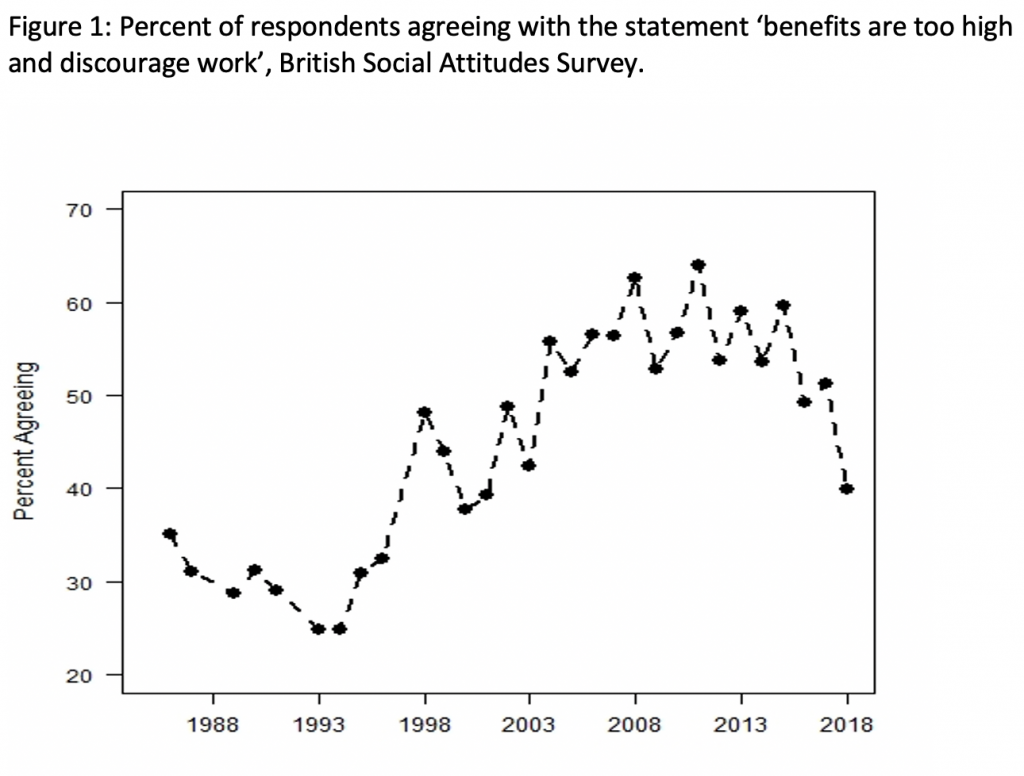

My explanation hinges on two other things that distinguish the UK from its continental neighbours. The first is public opinion. By 2010, welfare was at its least popular since long-term polling began in the 1980s. The public opposed redistribution, felt that welfare recipients were undeserving, and perceived welfare fraud as rampant. Figure 1 plots the percent of people endorsing the statement that ‘unemployment benefits are too high and discourage work’ over time in the British Social Attitudes Survey. It shows that the arrival of a new Conservative-led government in 2010 coincided remarkably closely with the system’s peak unpopularity.

Support had plummeted over the 1990s and 2000s, a change which was also not matched in other similar countries. This opened up a unique opportunity to enact drastic reforms that was not available to earlier governments. New archival work by Chris Grover unearthed a Conservative proposal for a benefits cap in the early 1980s that was very similar to the controversial cap was introduced in 2013, but was rejected by ministers as politically infeasible. By 2010, however, the cap was a vote-winner: one of its architects recently claimed that ‘when we tested the policy it polled off the charts. We’ve never had such a popular policy‘.

A key task in the book, therefore, is to explain why the public turned against welfare over the 1990s and 2000s. My explanation centres on the second thing that distinguished Britain from its European neighbours: discourse. Using methods of computational text analysis, I track how both politicians and newspapers described the welfare system and its users.

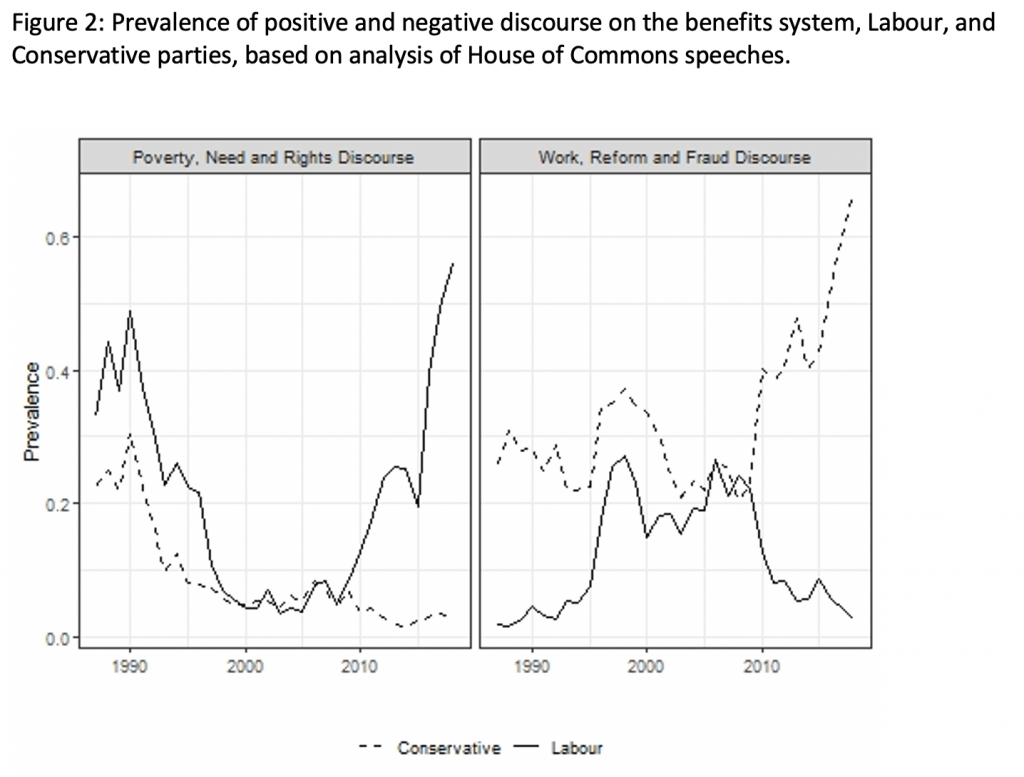

Figure 2 shows trends in political discourse, based on an analysis of all speeches made about welfare in the House of Commons from 1987-2018; in the book I show similar patterns for newspaper coverage. With a technique known as structural topic modelling, it measures the percent of time that politicians spent offering positive endorsements of the system (‘poverty, need and rights’ discourse) as well as talking negatively about welfare and its users (‘work, reform and fraud’ discourse). From the early 1990s to the late 2000s there was a bipartisan collapse in positive depictions of welfare, with Labour converging on the Conservative party in terms of negativity. From the late 1990s to the early 2010s, the public heard a constant barrage of criticism of welfare and its users, and very little praise.

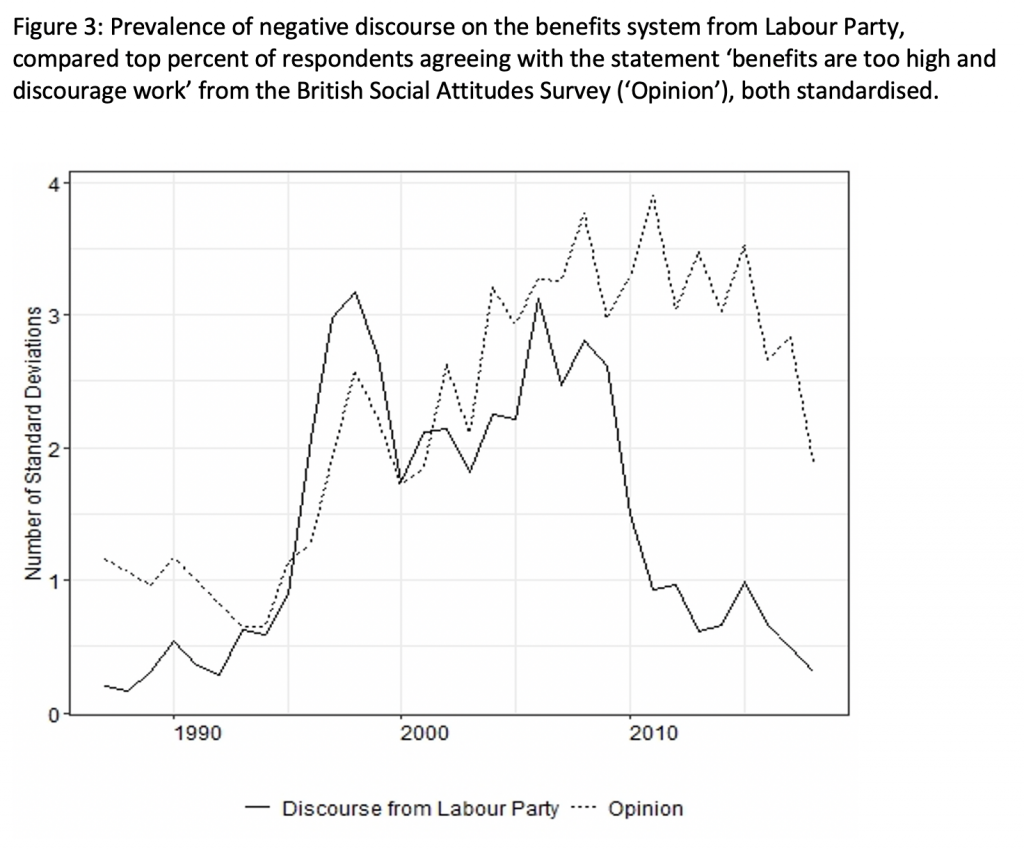

Later, the two main parties diverged, but the period of bipartisan convergence over the 1990s and 2000s was crucial because of what it did to public opinion. Figure 3 demonstrates that discourse and public opinion evolved remarkably similarly. It compares Labour’s work, reform, and fraud discourse to the opinion measure shown in Figure 2. Such a correlation does not, on its own, tell us anything about causation. But my core argument in the book is that public opinion changed in response to this changing discourse.

Theoretically, the idea of elite-led opinion change is highly plausible. Research from political behaviour shows that it is precisely under conditions of elite consensus that mass opinion change is most likely to occur. Other possible theories for the change hold little water. It wasn’t simply a thermostatic response, where the public demands lower government spending when it rises above some generally-preferred level. Labour introduced benefit cuts as well as intensive welfare-to-work reforms over the 1990s and 2000s, but the public kept wanting more cuts and greater punitiveness. It wasn’t due to a booming pre-crisis economy either. The system became ever more unpopular even during the financial crisis and its aftermath. Nor was it a middle-class revolt against working-class benefits users. All groups in society – all classes, income groups, education groups and even the unemployed – changed their views in the same way. In the book I also present multiple pieces of empirical evidence, including quasi-experimental and experimental work, that together point to changing discourse as the major influence on opinion change.

Thus what politicians and the media said about the benefits system and its users ultimately reshaped welfare policy. Ironically, Tony Blair and his allies hoped to bolster public confidence in the system by ending the ‘something for nothing’ culture. But by constantly critiquing it, they paved the way for historically unprecedented reforms after 2010. This should make politicians think carefully about how they talk as they ponder their response to Universal Credit and the cost-of-living crisis.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s new book published by Oxford University Press in 2022.

Tom O’Grady is Associate Professor of Political Science at University College London.

Tom O’Grady is Associate Professor of Political Science at University College London.

Photo by Tom Parsons on Unsplash.