The return of professional football matches around the world brought with it a welcome form of distractive entertainment, and with it a new reality for mass events: non-existent crowds. While the visual aspect of this was striking, it was perhaps the new auditory reality that was most unsettling; airwaves that once overflowed with the sound of multitudinous football fans were now peppered with strained calls from players, the sound of the ball sullen as it ricocheted around the hollow stadium.

It didn’t take long for sporting federations to spot the significance between the noise of the crowd and the level of entertainment though, adding this artificially to the broadcast. Both the Australian Football League and the German Bundesliga opted for deploying noise from previous games, while the English Premier League and Spanish La Liga are relying on sounds taken from the game FIFA 20. Adding to cultural authenticity, South African sound engineers were sure to include the sounds of the famous vuvuzela within their constructed noise. The American National Football League (NFL) is also airing artificial noise both within stadiums and on broadcasts.

Why is it that the noise of the crowd occupies a greater role in our enjoyment of sporting events than we might have first thought?

The crowd, the players and the home advantage

Most psychological studies into the impact of fan noise have focused on its influence on refereeing decisions. A study from 2002, for example, suggested that the noise of the crowd has the ability to become the “12th man” and potentially influencing refereeing decisions.

The noise of spectators can impact on the performance of players too. A study examining the impact of crowd noise reported that it makes up one of the key components that contribute to “home advantage”, along with other facets such as pitch familiarity. Not only does playing on home-ground contribute favourably to a player’s performance but so does hearing your home crowd there too. Liverpool are famously fueled by their “12th man” with their Manager Jurgen Klopp often calling on the crowd to push their team on. Liverpool’s win percentage in the twenty-six Premier League (PL) games prior to lockdown was 92%. In the twenty-six PL games since, their win percentage has dived to 54%. Many factors might be contributing to this, but it is tempting to ponder on the possibility that the team are missing the energy of their crowd more than others.

Viewer enjoyment is about what we hear, as much as what we see

Another aspect of the issue centers on the enjoyment of the viewer at home. A study published in the journal Computers in Human Behaviors reported that individuals watching TV were more likely to enjoy the experience when they thought more people were viewing simultaneously with them. Crucially, it did not seem to matter whether the other viewers were close or far away.

But what also matters is that people’s experience and whether or not they feel immersed is strongly influenced by sound, just as much as vision. As well as the relationship between sound and immersion, Professor Laurie Heller warns of a potential “audiovisual disconnect”, arising from the discrepancy between what is being heard and the empty rows of seats. There is certainly a potential for unsettling eeriness to arise when hearing the noise of thousands of fans, only to see empty seats. This seems to have been anticipated and addressed by the inclusion of seat covers and billboards in the stadia.

The contagiousness of canned laughter and emotion

Others have written on the connection between this development and Jean Baudrillard’s ideas around postindustrial society and hyper-reality, wherein spectacle ascends the hierarchy of importance as meaning descends; it no longer matters whether or not fans are in the stadium, the abstraction of noise without noise-makers matters little when the spectacle is more important than the real.

Another philosopher, Slavoj Zizek, writes on the quaintness of canned laughter, seeing it as a return to older societies. He sees parallels between it and phenomena such as the hiring of “weepers”, women who would be paid to cry at funerals. The artificial outpour of emotion, Zizek claims, acts as a sense of emotional discharge for the viewer. It is notable that TV shows such as Seinfeld, among the most successful series’ of all time, relied on canned laughter for every joke. Among its uses, canned laughter serves as a cue for the viewer: this is where you should laugh. It also taps into our propensity towards suggestibility: this is where other people laugh.

Behaviours can be famously contagious too – as well as serving as a cue, the artificial noise can serve as a tip in the balance of action, between reacting and remaining subdued. Seeing others engage and react, is likely to nudge viewers to do the same. As well as behaviours, emotions can be contagious; the emotions conveyed by the noise of the spectators serve to heighten the emotions felt by spectators. The presence of thousands aids in signaling the importance of the event; the sudden loss of this aspect of sports events can be lessened by the simulated presence of thousands by way of their noise.

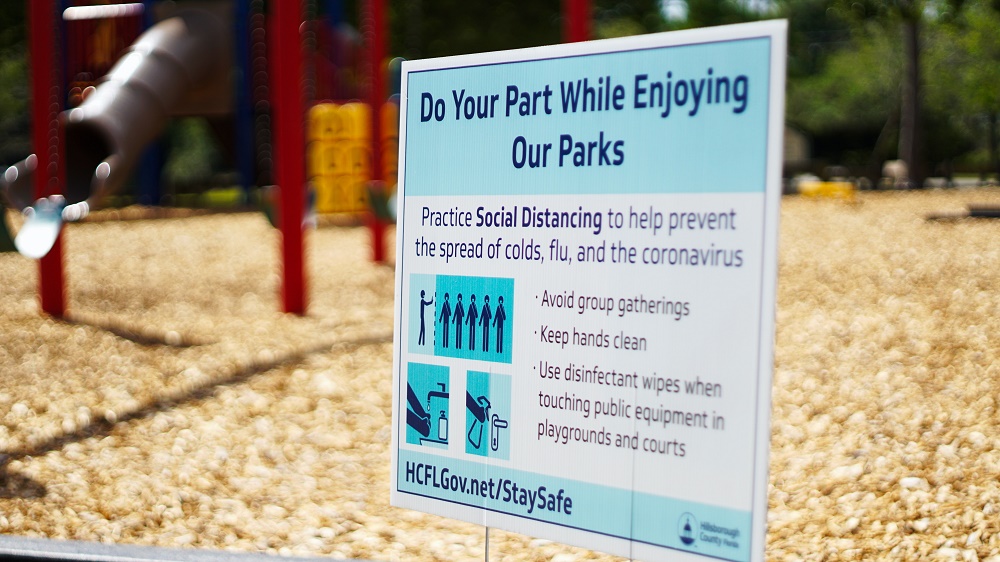

Perhaps more than anything, the comfort derived of hearing artificial fans could be a clamoring for a recent past that we are longing for, a time in which we did not have to think twice about what we touch and where we go. It might be worth considering what other aspects of our Pre-COVID lives we are missing, and what comfort blankets we might deploy, like the canned noise of sports fans, to soothe our sense of loss and help us adapt to new realities.

Notes

- The views expressed in this post are of the author and not of the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science at LSE.

- Featured image courtesy of Nathan Rogers on Unsplash

great post!

This article contains a lot of speculation and little evidence.

On many different forums, fans have either complained about fake crowd noise – or asked how to turn it off.

The issue is the disconnect between the action and the pictures.

Fans know that the shouts of coaches can be heard in echoey stadiums – but BBC and others are suppressing these.

In a small survey on a Fans Forum, nearly half described MOTD as “almost unwatchable”, preferring Football on Quest (Tiers 2,3,4) with its natural sounds.

While it is true that nearly half slightly favoured fake noise – almost none of those described LACK of noise as “almost unwatchable”.

The bias was clearly against fake noise.

Informative post. Thank you so much.