Your state of financial wellbeing could be affecting how you perceive and take financial risks, writes Executive MSc Behavioural Science alum Kanags Surendran.

Financial institutions and advisors continue to rely on single question subjective measures to determine individual’s financial risk tolerance, but research has shown that this approach is not prudent in determining portfolio allocations: there is a gap between what these scores indicate and how people really behave in relation to risk. In this post, Kanags Surendran explores current research and the results from a study conducted as part of the Executive MSc Behavioural Science programme.

What is financial wellbeing?

Literature suggests that over the years, multiple proxies have been used to define and measure financial wellness including, net worth, income, wealth, consumption and spending patterns, financial behaviour, financial knowledge, attitudes as well as financial satisfaction. Income has been used as a measure of financial wellness but has its limitations since income only measures a portion of economic wellbeing; it is not entirely reflective as it ignores wealth and consumption patterns (Weinberg et al., 1999).

Financial satisfaction is a measure that is also often used to define and serves as a proxy for financial wellness. Financial satisfaction is a subjective assessment of satisfaction with specific financial domains including income levels, ability to meet and deal with unexpected financial demand etc. While traditionally this was measured with a single subjective question, following a Delphi study amongst experts in the field, Prawitz et.al (2006), defined a measure based on a scale that assesses stress, satisfaction, comfort, worry and confidence of one’s financial situation.

What is financial risk?

Financial risk tolerance (FRT) is a behavioural finance term that is inverse of the economic concept of risk aversion (Marinelli et al., 2017). It is defined as the maximum amount of risk that an individual is willing to bear when making a financial decision (Grable, 2000), and is an underlying factor in financial models, investment analysis, portfolio management and decision making. It also influences behaviours: short term such as debt versus savings decisions, as well as long term investments such as retirement (Campbell, 2006). It is very reasonable to expect that people with different FRT will make different financial decisions.

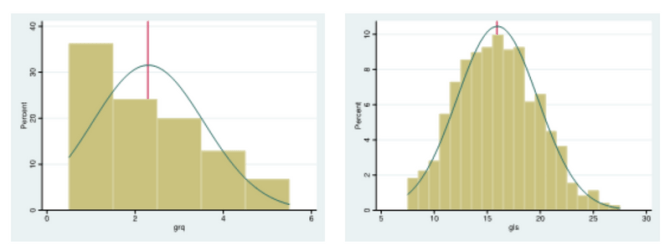

Risk is typically measured using a mixture of approaches. A single, simple question – the General Risk Question (GRQ) – is used by many to assess financial risk tolerance (Mudzingiri & Koumba, 2021). If you would have undergone a financial risk assessment you may have come across this question that asks you to rate your willingness to take financial risk from in a scale of 1 to 5. 1 is low risk where one is comfortable with just investing in low-risk deposits with no appetite for any loss and 5 where one is willing to take high risk with a bigger appetite for financial loss.

The question above aims to reveal perceived risk. However, this style of questioning may not reflect true risk tolerance as the question tends to be more reflective of choice attitude rather than actual risk. Historical response patterns indicate a large population have little risk tolerance, in conflict with actual observed behaviour (Chen & Finke, 1996; Grable, 2016). A 13-item risk scale was developed by Grable and Lytton (1999) called the Grable Lytton Scale (GLS) which has been tested and proven to offer acceptable levels of validity and reliability with Cronbach’s a of 0.77 (Kuzniak et al., 2015) and is more relevant as it measures revealed financial risk tolerance. Research has shown that there is a lack of consistency between revealed and perceived risk.

Park & Yao (2016) noted that gender, marriage, children, debts other than mortgage and access to financial planners influenced consistency. Financial literacy and financial sophistication have been proven time and again to reduce the gap between self-reported and revealed risk (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; Marinelli et al., 2017a; Mudzingiri et al., 2019). Literature however lacks sufficient studies on how one’s personal financial wellness impacts the coherence between the measures of financial risk tolerance.

Does financial wellbeing impact financial risk?

Our emotions, we know influence our decisions. Studies have shown emotions such as anger, embarrassment and frustration impair self-control leading one taking more risks and feeling sad could let people set low expectations (Leith KP et al). It is feasible that different levels of emotions associated with one’s sense of financial wellbeing could play a role in how they perceive financial risk, and those who are financially satisfied may have a better understanding of their financial risk. The study I did as part of my dissertation work aimed to understand this relationship. As part of this study, a randomised control trial was conducted across three groups of total 740 participants in Malaysia.

In one group, participants were asked information about their objective financial wellbeing as indicated by their financial portfolio and displaying the objective financial wellness indicators such as their liquidity ratio, total debt to asset ratio and their investment ratio, following which their subjective and revealed risk are measured. In the other group, the participants were primed by exposing them to not just the financial indicators but also questions around subjective financial satisfaction. The control group was asked their risk tolerance questions before they were asked details about their objective and subjective financial wellbeing. The subjective risk was measured with the single GRQ question as mentioned earlier. Revealed risk was measured using the Grable Lytton Scale. Financial Satisfaction was measured using the InCharge financial distress/financial well-being (IFDFW) scale.

What I found was in line with previous studies, that while most people indicate a low or no risk tolerance, their revealed risk is very different, and they could be behaving very differently, as shown in the graphs below.

The study showed that participants who had prior exposure to investment products or had a longer time horizon for investments had a better consistency between their subjective and revealed risk tolerance levels. Furthermore, older participants tend to also show a lower threshold of risk tolerance across both subjective and revealed measures.

Interestingly, subjective and revealed risk tolerance reduces with increased financial satisfaction, meaning if participants were satisfied, they were risk averse and if they weren’t, they took more risks. This is contradictory to previous studies that have indicated a higher financial satisfaction leads to higher risk tolerance levels (Grable, 2016). One possible explanation to this is that with increased financial satisfaction, participants don’t feel the need to take on more risk or it could be that the pandemic and associated economic situation may have played a role.

The study however failed to prove that priming for financial wellness impacts consistency between the subjective and revealed risk. However, among those who were financial satisfied, those who perceive themselves to be extremely risk averse or extremely risk tolerant, had a better understanding of their risk tolerance as shown by the narrow deviation between their subjective and revealed risk scores. For this extremes, as financial satisfaction improves, the difference between risk scores narrows thereby indicating that financial satisfaction helps improve understanding of participants risk tolerance levels.

The takeaway

The premise going into the study was that an individual’s financial wellness will play a role in influencing their risk perceptions. While individually the indicators seem to play a role, and while the study showed some effects for those at the extremes of risk tolerance, the study couldn’t establish that financial satisfaction or objective wellness indicators impacted risk tolerance. This could be due to the possibility that individuals do not rationalise their financial wellbeing using the indicators that were used in the experiment or that the subjective perception of wellbeing overrides the salience of any objective measures used in this study.

The research reinforces that subjective and revealed risk tolerance measures are not interchangeable and that relying on subjective risk as a metric will expose researchers and financial planners to reach unreliable conclusions. While we need more research to understand the exact role mental and financial wellness plays on risk perceptions, in practice, financial institutions and advisors continue to rely on single question subjective risk tolerance measures. My study adds on to existing literature that this approach is not prudent in determining appropriate portfolio allocations to end consumers given not just the unreliability of the same but also the degree of the variance between perceived and revealed risk.

Notes:

- The views expressed in this post are of the authors and not the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, nor LSE.

- Example study question and graphs sourced from “Financial Wellness and Financial Risk: Does increased financial wellness reduce the gap between subjective and revealed risk measures?” produced by the author.

Bibliography:

Campbell, J. Y. (2006). Household finance. Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1553–1604. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-6261.2006.00883.X

Charness, Ga., Gneezy, U., & Imas, A. (2012). Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences | Enhanced Reader. Journal of Economics Behaviour & Organisation , 87, 43–51.

Chen, P., & Finke, M. S. (1996). Negative Net Worth And The Life Cycle Hypothesis. Financial Counseling and Planning, 7, 96.

Leith KP, Baumeister RF. Why do bad moods increase self-defeating behavior? Emotion, risk taking, and self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996 Dec;71(6):1250-67. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.6.1250. PMID: 8979390.

Grable, J E, & Lytton, R. H. (1999). Financial risk tolerance revisited: the development of a risk assessment instrument. Financial Services Review, 8(3), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-0810(99)00041-4

Grable, John E. (2000). Financial Risk Tolerance and Additional Factors That Affect Risk Taking in Everyday Money Matters. Journal of Business and Psychology 2000 14:4, 14(4), 625–630. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022994314982

Grable, John E. (2016). Financial Risk Tolerance. Handbook of Consumer Finance Research, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1_2

Kuzniak, S., Rabbani, A., Heo, W., Ruiz-Menjivar, J., & Grable, J. E. (2015). The Grable and Lytton risk-tolerance scale: A 15-year retrospective. Financial Services Review, 24(2), 177–192. https://njaes.rutgers.edu/money/riskquiz/

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/JEL.52.1.5

Marinelli, N., Mazzoli, C., & Palmucci, F. (2017a). Mind the Gap: Inconsistencies Between Subjective and Objective Financial Risk Tolerance. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2017.1308944

Marinelli, N., Mazzoli, C., & Palmucci, F. (2017b). Mind the Gap: Inconsistencies Between Subjective and Objective Financial Risk Tolerance. Http://Dx.Doi.Org.Gate3.Library.Lse.Ac.Uk/10.1080/15427560.2017.1308944, 18(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2017.1308944

Mudzingiri, C., & Koumba, U. (2021). Eliciting Risk Preferences Experimentally versus Using a General Risk Question. Does Financial Literacy Bridge the Gap? Risks 2021, Vol. 9, Page 140, 9(8), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/RISKS9080140

Mudzingiri, C., Mwamba, J. W. M., Keyser, J. N., & Bara, A. (2019). Indecisiveness on risk preference and time preference choices. Does financial literacy matter? Cogent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1647817

Park, E., & Yao, R. (2016). Financial Risk Attitude and Behavior: Do Planners Help Increase Consistency? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37(4), 624–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10834-015-9469-9/TABLES/3

Prawitz, A. D., Garman, E. T., Sorhaindo, B., O’Neill, B., Kim, J., & Drentea, P. (2006). InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, Administration, and Score Interpretation – ProQuest. Association for Financial Counselling and Planning Education. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1355866363?pq-origsite=primo

Weinberg, D. H., Nelson, C. T., Roemer, M. I., & Welniak, E. J. (1999). Fifty years of U.S. income data from the current population survey: Alternatives, trends, and quality. American Economic Review, 89(2), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1257/AER.89.2.18