Through weaving together family history and anthropological fieldwork, LSE PhD student Gareth Breen considers one Taiwanese Christian group’s ‘circular’ concept of the Body of Christ, and how this notion sustains a self-understanding of ‘one church’ increasingly spread across the globe.

Within the various histories of Christianity the ‘Body of Christ’ has been what we might call a ‘glocalising’ image. On the one hand, the symbol and/or substance of Christ’s body is ingested ‘locally’ in the intimate ritual of the Eucharist. On the other, the Body of Christ is a metaphor for the global collective of Christian believers extended across space and time. How are Christ’s body as bread and Christ’s body as a Christian collective related in Christians’ lives? The relative importance of these local and global forms of the Body of Christ is of course tied to particular Christian traditions, cultures and life-trajectories. In this article, I briefly explore to what extent the local and global are tied together in Christ’s body for a group of Christians in Taiwan I did my PhD research with in 2015 and 2016.

These Christians are part of an international Christian primitivist group founded in the 1920s by a Chinese itinerant preacher who later named himself “Watchman Nee”. Escaping communism in the late 1940s, much of the group moved to Taiwan and grew sevenfold there under the leadership of Nee’s ‘co-worker’, “Witness Lee”. There were 70,000 participants in 1949. Now, according to church estimates, there are up to two million. A basic principle of the group is that there is only one church in the world and that it should be divided only by geography and not by doctrine or name. Thus my informants called themselves only ‘the church in Taipei’. Those meeting in Palo Alto, California call themselves ‘the church in Palo Alto’, and so on. There are many such ‘localities’, as they are termed, worldwide. A very frequently used metaphor which the church employs to describe itself as a global social entity is “the Body of Christ” or, more often, just “the Body”.

I first encountered the church when my parents joined what their Christian friends at the time called ‘a Chinese church’ as I turned 13. The life of our family shifted in many ways at that time, but a key difference demarcating the period before and after this transition, in my memory, was the taste and shape of the Eucharist bread. Fifteen years before joining this church, my father read a translation of one of Watchman Nee’s key texts and left what Nee, and now he, called “Christianity” for good. Before discovering the church Nee founded, my father met several times a week with a few other Christians, disillusioned with Christianity, in our living room. They wrote their own hymns, baked their own Eucharist bread and communed over their mutual love for Nee’s teachings and biblical exegeses. The bread my mother baked on Sunday mornings was unleavened. This practice was based upon Corinthians 5:8:

Therefore let us keep the feast, not with old leaven, neither with the leaven of malice and wickedness; but with the unleavened [bread] of sincerity and truth. (KJV)

But all my age-mates and I knew that it was fragrant and tasty. A dense, doughy, sweet lump, topped with a flaky crust, it probably did more work than we knew in keeping our little house church together. After joining the now-global church that Watchman Nee founded and Witness Lee expanded, the taste of the standardised circular wafer that arrived in bulk at our house paled in comparison. Of course, this wasn’t a major concern at the time: I only associate the two breads with the two life-stages in retrospect. Nevertheless, it seems to me that the circular Eucharist wafer is part of a transnational set of standardised, but dynamically employed, affordances which give rise to a sense of the church’s globality. If each locality were to bake their own bread, the sense of sameness across church localities would, to an extent, be undermined. While the doughy, unleavened lump tasted of home, the disk wafer tasted of the global Body.

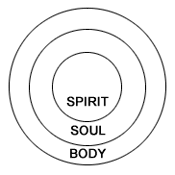

The circularity of “the Body” is not limited to these wafers, however. An important foundation of the church’s ministry is that ‘Christianity’, especially ‘Western Christianity’, has long lost contact with God because of its assumption that humans are composed solely of a body and a soul. To demonstrate this idea, the church has a very important diagram to educate its participants and potential converts. The diagram is simply three concentric circles which demonstrate that humans are made of three distinct parts, or ‘organs’: body, soul and spirit (Fig 1).

It is only with the realisation that one has a third distinct organ to ‘contain’ God, the human spirit, that God can truly ‘enter into’ you and ‘flow’ around the Body, members say. What I want to draw out here is the distinctive way in which the human bodies that compose the divine, collective ‘Body’ are also imagined to be circular by my informants. Paying attention to the particular shapes which collective, transnational imaginaries take is important for our understanding of how religion connects and separates people across purported ethnic, political and cultural boundaries.

Circularity extends beyond even the shape of objects and ideas within the church. From the beginning, Watchman Nee and those who understood him to be a modern-day apostle rejected ‘the sin of denominations’. If the purpose of the universe was that Christians would become the living Body of God, then denominationalism was a dismemberment of that body. Many denominational Christians understand each group to be fulfilling a separate function of the Body – just as the hand does something very different from the eye, so too do Charismatic denominations, through the ‘gifts of the Holy Spirit’, do something very different from traditional Anglican churches, for example. Thus it is natural for such Christians to ask one another, ‘what church do you go to?’ This question, to those committed to the church in Taiwan, sums up a lot that has gone wrong with ‘Christianity’– there is only one church and it is the Body of God in becoming, they say. Though using the same term as denominational Christians, Nee clearly had very different ideas about what ‘the Body of Christ’ looked like.

The bodily image that denominational Christians give to the church as a whole, Nee, Lee and my informants in Taipei give to a single ‘locality’. All members there have very different roles to play in maintaining the health of the local group. There is no clergy and all are expected to speak in church meetings and evangelise outside of them. Nonetheless, it is recognised that every ‘saint’, as participants are referred to, has their own ‘function’. Some may be better at cooking, others better at looking after newcomers, or conducting children’s meetings, or updating the church’s social media sites etc. The church as an international entity, however, is not to be divided up this way. I want to suggest then that the ‘Body of Christ’, on this scale at least, is imagined in the way that the human body and the Eucharistic Body are – as circular. Structurally, unlike the outline of a human body, a circle looks the same whichever way one rotates it. Whenever I ask church participants what they feel is distinctive about their own locality they invariably preface their reply with ‘the church is the same everywhere’.

Finally, in contrast to how the church in Taiwan imagines the situation to be in “Christianity”, in almost every church meeting – whether there are three or three thousand participants – members sit in a circle. In this church then, the global metaphor of ‘the Body’ takes an implicitly circular shape in idea, object and practice. It is the circularity of the Body metaphor in this church which is moved and moves across the globe.

About the author

Having studied anthropology at UCL before starting his PhD in anthropology at the LSE in 2013, Gareth is now writing his thesis on transnational Christianity in Taiwan. His research interests include Chinese and Taiwanese histories, religious experience and urban living, rhythm, metaphor and social epistemology.

Having studied anthropology at UCL before starting his PhD in anthropology at the LSE in 2013, Gareth is now writing his thesis on transnational Christianity in Taiwan. His research interests include Chinese and Taiwanese histories, religious experience and urban living, rhythm, metaphor and social epistemology.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.