Justifying his invasion of Ukraine, Putin sought the “denazification” of Russia’s neighbour. The absurdity of this justification is not only exposed by the rapidly rising profile of Ukraine’s president, who is Jewish, but by the long history of Judaism in Ukraine. In this timely post, Dr Marina Sapritsky-Nahum writes about the Jewish community in Odesa and the impact this war has already had on their Jewish and Ukrainian identities.

I first arrived in Odesa, Ukraine, in 2005 as an anthropologist. I was conducting ethnographic fieldwork among the local Jewish population who, going against the grain of mass migration, had decided to stay in the city or had emigrated and returned. I studied how the specific history of Odesa, a cosmopolitan and Jewish city, shaped the identity formation of Odessan Jews who were entangled in various projects of Jewish revival on the ground.

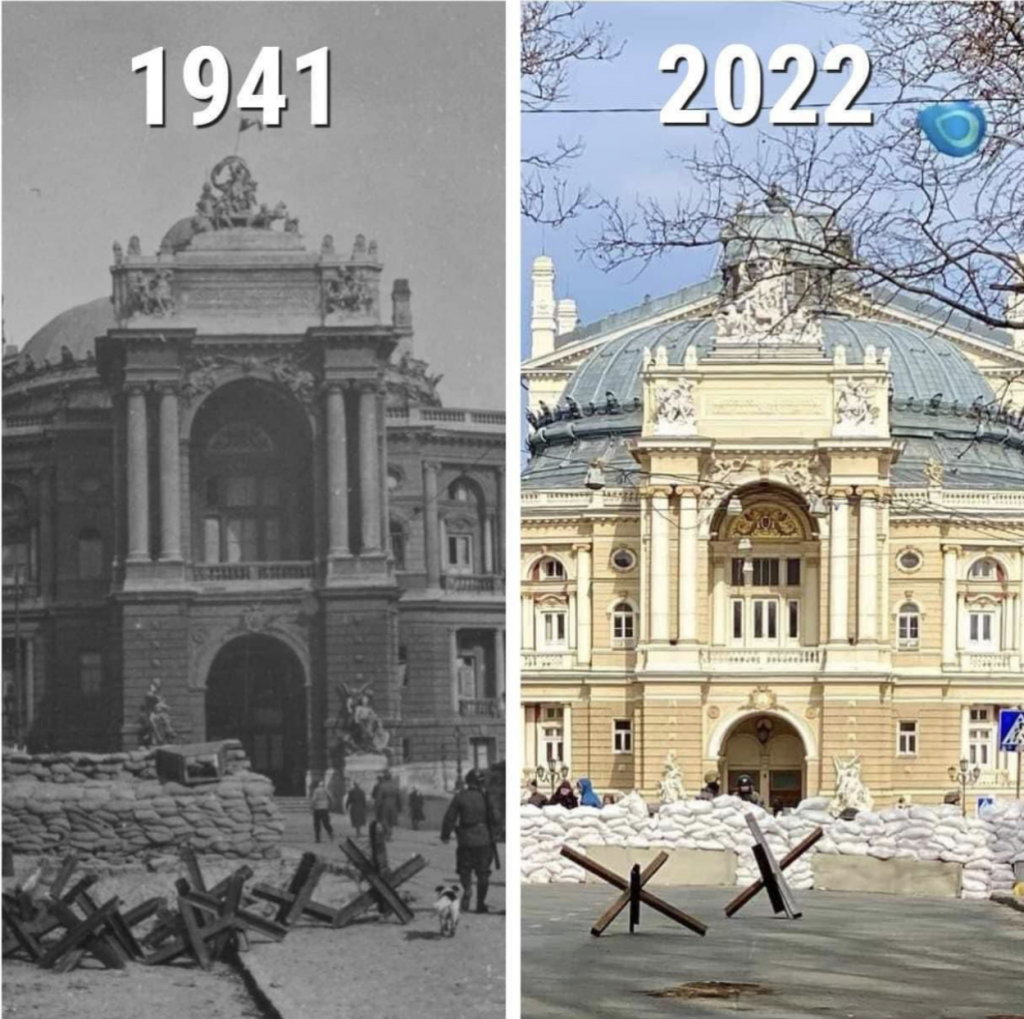

At that time, Odesa’s Jewish population of nearly 30,000 people was predominantly Russian-speaking. Few of the people I met saw themselves as Ukrainian, even though they lived in Ukraine; some adamantly dismissed the rhetoric and policies of Ukrainian nationalism. The Jews who had left the territory of Ukraine during the Soviet regime felt even less connection to being Ukrainian. “I spoke Russian, therefore, I was Russian” was a common reference for ex-Soviet Jewish emigres and their children who left the country in the 1970’s. For Odessan Jews, home and abroad, the horrific war waged by Putin on 24th February 2022—one that is tearing apart their ancestral home, and humanity at large—has solidified their identity as Ukrainian Jews.

Jews and other Russian speakers living in Ukraine have been “shedding their Russianness” in favour of Ukrainianness, particularly after the political reverberations of 2013–2014’s Euromaidan protests. For Ukrainian Jews abroad, who previously identified as “Russian” and were dubbed as such by the media and on the street, this change came overnight when Putin invaded Ukraine under the pretence of “protecting Russian speakers.”

“Until today’s war, I would say I am Russian,” said a Londoner whose family emigrated from Odesa in the 1970s. “My parents left when Odesa was still part of the Soviet Union. They never spoke Ukrainian; we thought of ourselves as Russian. Whenever someone asked where my family was from, I would say Russia. But not today. Now I tell my children that we are Ukrainian.”

The war in Ukraine has united Ukrainians of all faiths like nothing the world has ever seen. It has created a strong sentiment among people in Jewish communities across the country and around the world that they are Ukrainian, whatever their linguistic differences, citizenship, or birthplace. They are part of Ukraine’s fight for independence, justice, sanity, democracy and freedom. In his fight against evil, the country’s Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelensky, has won the hearts of the world by his bravery and loyalty to his people.

But Zelensky has also proved to be the face of the new Ukrainian Jewry. Strong, proud, brave and resilient, he is being called the world’s “Jewish hero” and a “symbol of the nation.” Twitter posts that read “Zelensky is my president” are blasting around the world, revealing the international community’s admiration for a leader who, despite being Putin’s number one target, has declined “a ride” to safety.

Zelensky may be Jewish, but his Jewishness did not really matter in his initial campaign or during his presidency—until now. He did not make it a topic of importance, and nor did others. But when Russia accused Zelensky of leading a Nazi state to justify Putin’s invasion and “denazification” of Ukraine, Zelensky’s Jewishness became prominent pieces of his identity (Zelensky’s family died in the Holocaust during WWII, and his Jewish grandfather Semyon heroically fought in the Soviet Union’s Red Army to defend Ukraine from the Nazis). Zelensky’s story makes clear to Putin, to the Ukrainian people and to the rest of the world that Ukraine is not defined by its dark history of collaboration with the Nazis, but rather by its bright path forward, paved by a Ukrainian Jewish leader. In this context, Zelensky’s Jewishness matters all the more, and serves to ridicule Putin for his claims to “protect” Russians in Ukraine. A joke told in Odesa depicts the absurdity of Putin’s arguments in the eyes of local Jews: “Two men on the street are speaking Yiddish. A third comes up and asks why they’re not speaking Russian. One of the men replies, ‘I’m too scared to speak Russian. If I do, Putin will show up and try to liberate us!’”

Odesa, founded by the Russian Empress Catherine the Great in 1794, once had the third-largest Jewish population in the world. At the end of the 19th century, Jews played a pivotal role in the creation of Odessan culture. Because of the city’s ethnic composition, apolitical atmosphere and “the primacy of local over national identity,” Odesa has been described as “unique,” a state within a state. Today this distinction is an observation of the past, not the current reality. There is no difference between Kharkiv, Dnipr, Melitopol, Chernihiv, Kyiv, Odesa, or Lviv—all are Ukrainian cities under attack, where local Jews and many of their community leaders who are foreign nationals stand with Ukraine. The ethnic, religious and linguistic distinctions that once painted these cities as “Ukrainian” or “Russian” to the world no longer carry the same meaning. Posts on Telegraph, the preferred communication platform among Ukrainians during this war, are written in both Russian and Ukrainian. Ukrainians are not separated by their language, but united by the common idea that Ukraine matters, has the right to exist and is under deadly attack. “I am not fighting for Ukraine because I’m a Ukrainian national” says a young Odessan who lives in Tel Aviv. “I’m fighting as a humanitarian for the people I love.”

Some of my friends in Ukraine have now crossed the border of Moldova and Poland to find safe refuge. Others are lined up for days at the border, on the brink of exhaustion, or making emergency plans for departure. But most remain exactly where they were, ready to defend their city, displaying great acts of bravery while knowing their loyalty to Ukraine can cost them their lives. “I am not going anywhere,” Igor, a thirty eight year old resident of Odesa tells me, “I have enlisted and am ready to fight and die for my home.” In the quiet hours of curfew, he and a group of other armed men patrol the streets and send messages to neighbours and close friends checking up on one another with updates and offers of food, medicine, and other support. Putin gravely underestimated the Ukrainian people’s solidarity, strength, and courage to stand together for Ukraine and defend it at any cost.

“Russian warship … Go f**k yourself”—the message of the soldiers on Snake Island, who were captured by the Russian army—did not just demonstrate the resilience of the Ukrainian people but exemplified a “heroism worthy of the darkest days of World War II.” It showed the world that Ukrainians and Russians are not one. This is a hard reality for a country where many citizens have relatives and friends in Russia, speak Russian and are connected in some way or other to the ex-Soviet Russian-speaking culture. But it is neither kinship, nor friendship, nor language that binds Ukrainians in the midst of war. Rather, it is the understanding that Ukraine is a sovereign state, it is their home, and their home is under attack.

In sermons, leaders of Jewish congregations are recounting themes of Jewish bravery and survival of a few at the hands of the many by connecting the war in Ukraine with the stories of Hannukah, Purim and even the Jewish exodus from Egypt. Rabbi Shlomo Levitansky, a Chabad Lubavitch shaliach (emissary) in Sumy, a city on the Russian-Ukrainian border, is fully dedicated to supporting his community despite the danger involved in staying in a war zone. He is one of the 183 Chabad shluchim (emisarries) in Ukraine and other community leaders who have decided to remain in their cities. “It is so scary here, but I cannot leave? I have my Migdal family here” wrote the head of Migdal, the Jewish Community Centre in Odesa as the city was getting bombed. Levitansky believes that even non-Jews are inspired by Jewish stories of survival. In a webinar organised by Chabad Belgravia, he tells how Christian faith leaders in the city of Sumy are building hope around the story of Jews surviving in the desert with no other food but manna in their escape from Egypt. “Empty shop shelves and a shortage of wheat and other products leave people looking for something spiritual, a higher force,” he says. In a message posted on Facebook, on Shabbat and the second day of the war, Rabbi Avraham Wolf of Odesa keeps up his congregation’s spirits by reminding them to “Think good, and things will be good.”

Putin’s war has killed people and destroyed places and ideologies, but it has also birthed the strongest Ukrainian sentiment around the world. It is paving the way for a new chapter of Ukrainian-Jewish relations and a shared identity as Ukrainian Jews.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Beautiful and poignant!

Putin deranged idea that Russian speaking Ukrainians would choose oppression over freedom because they happen to share a language was a grave miscalculation.

And yes, Zelensky has managed to become the hero we all needed, brave and honorable, with an unshakable and inspiring love of his country. Putin does not understand the shockwaves it will send through the world if Zelensky is killed. His death will have the force of 100 nuclear bombs!

Thank you for this beautiful gift!

Brilliant and powerful article. Thank you.

An insightful and important piece.