In this piece, Dr Iman Dawood analyses the intersecting factors impacting Salafi women’s access to university, including issues with gender-segregation, interest on student loans, and class-based barriers.

The subject of Muslim women’s education has repeatedly made headlines in recent years. Global news stories about attacks on female students in Nigeria and Pakistan by actors claiming to speak in the name of Islam, like Boko Haram and the Taliban, have garnered much attention. More recently, the banning of women from universities by the Taliban in Afghanistan has also provoked widespread anger and condemnation around the world by Muslims and non-Muslims alike. It is thus no surprise that Islam, and particularly ultra-conservative approaches to Islam, are frequently seen as hampering Muslim women’s education in both Muslim-majority and Muslim-minority countries. This is certainly how Salafism, an ultra-conservative Islamic movement, is commonly perceived.

Within Europe, Salafis compose a small minority of the Muslim community. Though Salafis are sometimes lumped with groups like ISIS, the overwhelming majority of those who ascribe to Salafism strongly condemn terrorism. Their focus is on the purification of their faith through the emulation of the beliefs and practices of the Sahabah, Tabi’un and Tabi’ al-Tabi’in (the first three generations of Muslims) as strictly as possible. Though this approach to Islam means that Salafi gender norms have tended to be quite traditional (for example, enforcing strict gender segregation or privileging the role of women in the home), my fieldwork with Salafi communities in London between 2017-2020 suggests that the relationship between women’s education, particularly higher education, and Salafism is much more complex than is typically assumed.

I found that although some Salafi discourses discourage university attendance in co-educational settings, many women in Salafi communities have contested Salafi gender discourses, contributing, at least in part, to a slight shift in Salafi discourses over the years. Salafi gender discourses have thus rarely hindered women’s higher education in Salafi communities. Instead, I argue that we need to look at government policies (such as those on tuition fee limits and student loans) to understand why some Salafi women have been unable to go to university.

Salafi Discourses & Contestation within the Salafi Community

During the 1980s and 1990s, when the Salafi movement was a new movement just taking off in London, some Salafi preachers warned against young Muslim women attending university. The main reasoning behind this was not that women’s education per se was problematic, but that attending university would result in intermingling with the opposite sex, or what is commonly known as “free-mixing.” Despite circulating discourses about the dangers of university attendance, during my interviews I was surprised to find that, out of more than twenty-five women who had come to Salafism during this period, only two had heeded these warnings and decided against attending university.

Indeed, I found that discourses about the dangers of attending university were frequently contested by women in Salafi communities who had found other elements of Salafism quite attractive, such as its approach to creed and its focus on modesty. One of my interlocutors, for example, explained: “I always wanted to go to university, it’s something that I always wanted to do. I just didn’t believe the argument they gave me. I thought, how do you have female doctors […] and midwives? How do you have female anything if you don’t allow women to go?”

I also came to find that decisions not to attend university, or to attend but to study female-dominated degrees such as teaching, were at times reversed later in life by some Salafi women. This suggests that gender discourses are filtered, negotiated, and at times rejected, even within a highly conservative community like the Salafi community.

Perhaps at least partially owing to these processes of contestation, Salafi discourses around women’s higher education have also shifted slightly over the years. While carrying out fieldwork between 2017-2020, I found that these discourses are no longer a key message of Salafi preachers. Not only did I rarely come across discussions on the subject during my fieldwork, but in my interviews with Salafi leaders, I found a more balanced approach to the subject. Da’wah Man, a Salafi preacher popular with youth, explained, for example, that he believes that British Muslims should only attend university if the potential benefits outweigh the harm. He said that he tells both young men and women not to go to university simply for the sake of going: “[I tell them] go to university to get skills you need. If you want to be a doctor, ok go. If you want to be an engineer, go.” Today, women in Salafi communities also have several highly educated role models in the community, such as Naheed Anwar, a prominent member of the Salafi community who has recently obtained her PhD.

Financial Obstacles to Muslim Higher Education

While Salafi discourses warning against university attendance do not seem to be as prevalent today, the number of women studying for degrees, or intending to study for a degree amongst my young (16-25 year old) interviewees, was lower than I expected (especially in comparison to the number of older Salafi women who had gone to university). This was initially quite puzzling to me—as I had assumed that Salafi gender discourses would be the main determinant behind higher education levels in the community. Upon further investigation, however, I learned that affordability was the main reason behind decisions not to apply for and/or attend university. Several of the young women I spoke to explained that they simply could not afford university tuition. Perhaps this shouldn’t have been too surprising, as the government has raised the cap on tuition fees to £9,000 a year in 2012 making university education less affordable to many low income families. This has disproportionately affected the Muslim community, which faces many economic disadvantages. In fact, according to the latest census, 39% of Muslims in the UK are now living in the most deprived fifth of local authority districts, and almost 482,000 more Muslims now live in the most deprived locales than in 2011.

My interviewees also lamented their inability to take out student loans because these loans incur an interest rate of RPI plus up to 3%. This added interest is deemed by some Muslims to be a form of impermissible riba (usury) associated with exploitative gains in business transactions. Though one Muslim scholar, Haitham al-Haddad, has issued a fatwa (Islamic edict) claiming that student loans are lawful, this scholar is not deemed authoritative by all Salafis in the community. Many Salafis (male and female) thus find themselves with few options. A couple of my young interviewees managed to find ways around this predicament by undertaking a degree apprenticeship or by enrolling in programmes that don’t have tuition fees, like public health nursing/visiting. However, this was neither possible for all women nor all degrees.

Indeed, the limited availability of student finance options is an issue affecting other British Muslims, and not just Salafis, who also feel forced to choose between their dreams of attending university and their faith. Despite vows by former Prime Minister David Cameron in 2013 to tackle the financial exclusion of British Muslims by supporting Islamic finance initiatives, the options available to British Muslims keen to avoid interest-based loans remain very limited. Supporting Islamic finance initiatives would undoubtedly be a step in widening participation in higher education and breaking the cycle of poverty entrapping British Muslims.

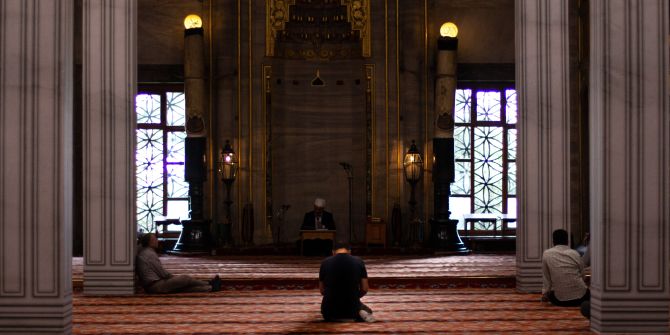

Photo by Omar Flores on Unsplash

This is a valuable resource and an astute research paper by Dr. Dawoid. From her fieldwork with female graduates of Saladin backgrounds Dr. Dawood indicates that the Salafi innate caution of male – female association on eg University campuses there is also the £9000.00 per annum fees to be met. This is an even more likely barrier for aspiring HE students.

A thoughtful and competent research based Paper. Revd Dr. Ian G. Wliiams.

A good read Mashaallah.