For decades, social scientific study of religion has been dominated by the secularisation question: is religion growing or declining? But this has distracted us from asking how religion itself is changing and, in turn, changing understandings of identity, political participation and citizenship for millions of people around the world. Ahead of our upcoming #LSEFestival panel discussion, Erin K. Wilson introduces some of the current trends in the changing nature of religion. Join us for the full discussion on Saturday 17 June 2023, 11.00 am to 12.00 pm

Is religion changing in the 21st century? The short answer is yes, of course it is, because religion has always changed. Despite this reality, the idea that religion is static, unchanging, traditional, and backwards persists in public consciousness. Yet if we consider specific practices such as prayer, rituals such as communion or pilgrimage, leadership structures, belief systems, and more, we can see that they constantly change over time and from place to place.

The Christianity practiced by members of the Church of England, for example, is very different from the Christianity practiced by Pentecostals. Attitudes towards the roles of women and people who identify as LGBTQIA+ differ both within and across religious traditions. The objects of worship are also different from one religious tradition to another (a monotheistic God in some traditions, multiple gods in others, sages and teachers in yet others, and the natural world in still more).

Thus, rather than asking “is religion changing?” or even “how is religion changing”, a more puzzling issue is why the fact that religion changes is apparently so surprising. What is it about how we currently understand “religion” that makes the idea of change seem so unusual, noteworthy, even controversial? Perhaps the more pressing issue is to change how we think about “religion” itself, especially in Euro-American contexts, so that we notice and comprehend the changes within and across religious traditions in different times and places.

Part of the problem is that we continue to reduce a vast, complex, and diverse set of phenomena to the simple, catch-all word “religion” (singular), covering everything from institutions, NGOs, rituals, belief systems, and identities. This practice suggests that there is something that is identifiably “religious” about all these different things that we label as “religion” and that neatly distinguishes “religion” from that which is “not religion”.

But what exactly is that? No one seems to agree on what this ineffable “religious” characteristic is, although some observers will say we simply “know it when we see it”. The nearest satisfactory explanation of this supposedly common religious denominator is concern with the transcendent and the existential – but then humanism and atheism also attempt to make sense of the transcendent and the existential, so that does not really resolve the issue.

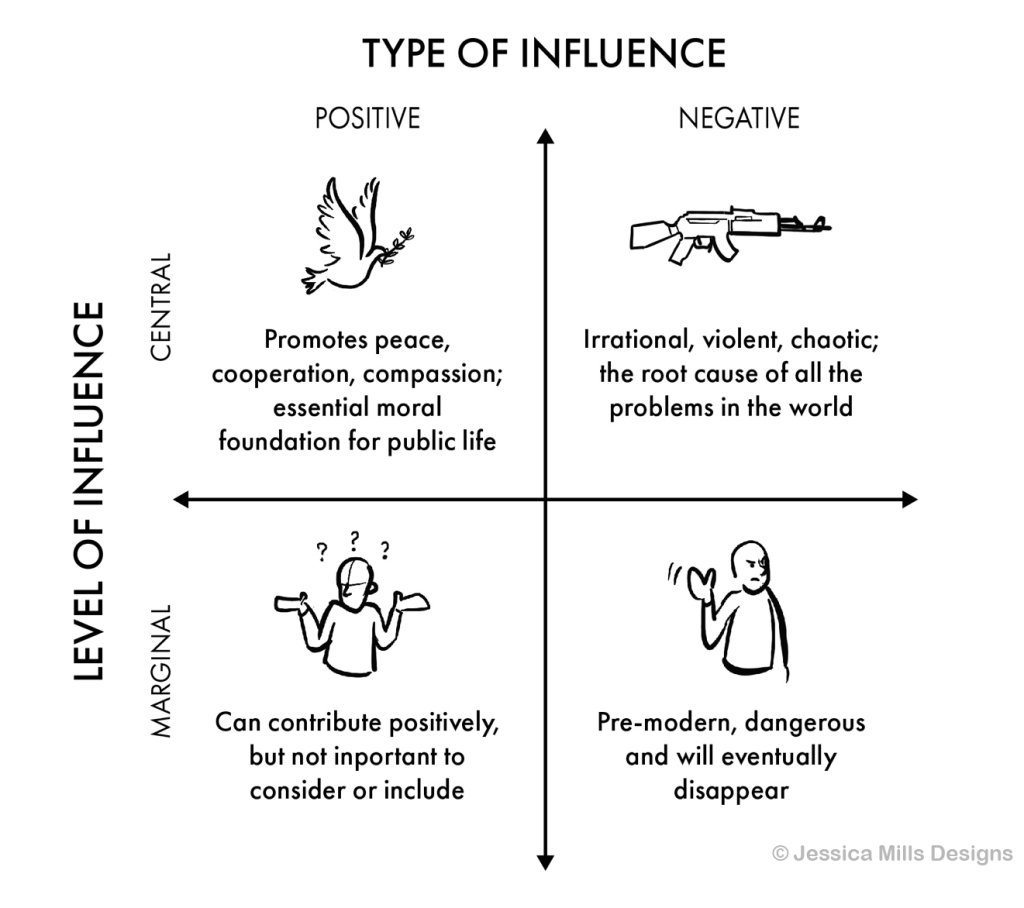

The word “religion” itself, then, represents our first problem. It is too imprecise and carries too many implicit assumptions and biases. We often assume that we all mean the same thing when we talk about “religion”. Yet none of us really know for sure what exactly someone is referring to when they use it, even when we use it ourselves. Common understandings of what religion is and does in the world can be neatly summarised into the four views presented in the matrix below:

While these views differ regarding how they think about religion, common across all of them is the idea that there is something that we can clearly identify and label as “religion”. What is not clear is exactly what that thing is. Given the diversity of views about what religion is, as well as the plurality of traditions and practices noted above, it is highly unlikely we will ever agree on what “religion” is.

Thus, rather than using such a slippery concept as our point of departure, it may be more productive to begin with something more concrete – context. What does “religion” mean for people in the UK? What does it mean for people in London compared with people in Birmingham, for example? How has the meaning of religion for people in the UK changed in the last 50/100/200 years?

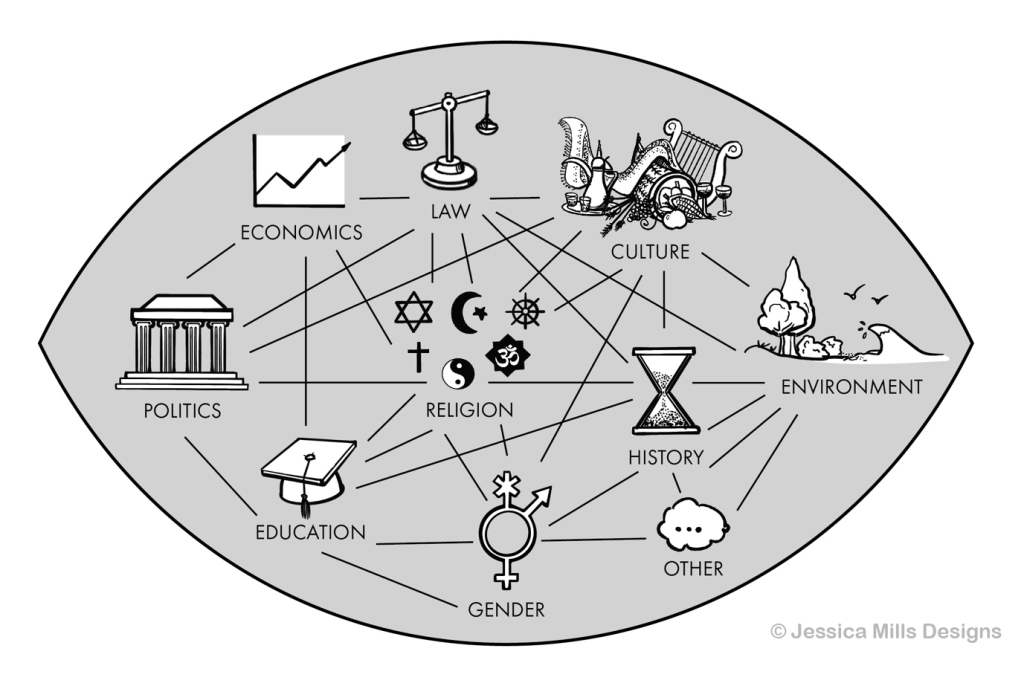

What does “religion” mean for indigenous Australians versus settler or immigrant Australians? Is “religion” even the appropriate word to use for indigenous cultures and spiritualities? How is religion’s meaning entangled with and dependent on other factors such as politics, law, nationality, gender, class, race, education, language, location, and time?

Starting with context, however, still only gets us so far, unless we also bring more precision to the term “religion” itself. Rather than asking “how is religion changing”, for example, we could instead ask – How is religious leadership changing (within specific contexts and traditions)? What is the impact of technology on religious rituals? How are people engaging with transcendental and existential issues in the 21st as opposed to the 19th century? How are the role and authority of religious institutions in politics and public life shifting? How, when, and why do religious stories, metaphors, rituals, and imagery influence public rhetoric?

To capture these diverse aspects of religious phenomena more adequately, we can refer to religious actors, religious identities, and religious narratives, rather than just to the undifferentiated category of “religion”:

Why does employing a more differentiated understanding of religion matter? No doubt there are scholars and analysts who would say that it doesn’t, that “religion” is just a distraction from core concerns, a tool instrumentalised to achieve strategic political goals. That may well be the case in some circumstances. But not in all. And, whether we “like” religion or not, whether we think religion is a positive or negative force in politics and society, it is an inextricable part of the human experience. That is why understanding what religion means and does for people in their daily lives, as part of their lived realities, matters.

This article is a summary of the core ideas and arguments in the author’s latest book, Religion and World Politics: Connecting Theory with Practice (2022, London: Routledge). You can buy the hard copy of the book or download the electronic version for free. All images are copyright of Jessica Mills Designs, commissioned by and produced for E.K. Wilson and Routledge. Reused here with permission. The author will be one of the speakers at the LSE RGS #LSEFestival event on the changing nature of religion on 17 June 2023.

This blog originally appeared on LSE EUROPP and is republished with permission.

Photo by Sofia Cangiano on Unsplash