Until health conditions intervened, Pope Francis was due to attend COP28, which would have marked the first in-person papal presence at the UN Conference of the Parties. The intention remains, and in this article Kristian Noll looks at why his attendance is important.

All eyes are on Dubai this week as world leaders, diplomats, academics, and journalists from around the world descend on the United Arab Emirates for the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP 28). Among them was to be an unprecedented guest: the Pope.

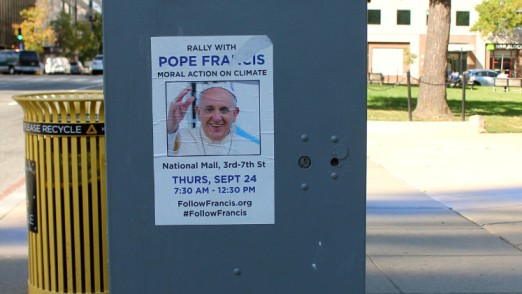

Since his selection in 2013, Pope Francis has placed climate protection at the centre of his unusually activist papal agenda. In a break from precedent, Pope Francis has leveraged his platform as both a global faith leader and political leader to consistently advocate for a more urgent and effective climate governance regime to slow global warming. Through his ground-breaking apostolic exhortations ‘Laudato Si’ (2015) and ‘Laudato Deum’ (2023), Pope Francis has centred climate protection in the agenda of the Catholic Church, and his plans to attend COP28 in person demonstrated his desire to extend his influence to climate governance paradigms.

On November 29, the Vatican announced that the Pope’s trip to the conference had been called off due to ill health. According to Matteo Bruni, the Vatican spokesman, all efforts would nonetheless be made to ensure that Pope Francis can participate in the ‘discussions taking place in the coming days.’

Although perhaps not in person, the Pope’s intense involvement in the COP process is significant for three key reasons.

First, there are an estimated 1.36 billion Catholics worldwide – 17.7% of the world’s population. While the Pope, like any leader, cannot influence the opinions of each of his followers, his deliberate rhetoric aligning climate action with Christian faith has had an incredible symbolic and political impact in the environmental policy space.

Second, the Catholic Church alone controls 177 million acres of land, an area greater than the US state of Texas, and more than 5,000 churches and investment properties around the world. Insofar as the building and land management sectors are critical in combatting global warming, engagement with institutions controlling these assets is critical.

Third, the Pope’s engagement with the global climate governance regime represents the extent to which faith-based organisations (FBOs) have been integrated into the global climate governance regime. At COP 28, the first-ever interfaith pavilion will highlight a multifaith understanding of climate change and the environmental advocacy of faith-based organisations (FBOs). Faith leaders have also been involved in the policy process: at the beginning of November, the Global Faith Leaders’ Summit took place, also in Dubai. Here, twenty eight faith leaders came together to sign the ‘Confluence of Conscience: Uniting for Planetary Resurgence’ declaration, committing faith communities globally to raising climate ambitions.

The incorporation of faith communities and perspectives into the COP process should be welcome, as a greater level of interaction between faith communities and the global climate governance regime is critical. Countries and regions where the consequences of climate change are most pronounced are also the most religious, and data from Pew Research indicates that religiosity in these regions will only become more pronounced as we hurdle towards the pivotal climate year of 2050. Moreover, FBOs play critical roles as material asset holders. According to the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), FBOs control 8% of the earth’s habitable land surface, 5% of all commercial forests, 50% of schools, and 10% of financial institutions globally. Finally, FBOs have been largely receptive to calls for climate-conscious policy. Indeed, FBOs account for more than 35% of all global divestment commitments, the Church of England being the most recent institution promising to divest from fossil fuels.

The Importance of Centring Religious Literacy in Climate Discussions

Engagement with FBOs in climate governance is crucial; however, we must be incredibly careful with how it is done. International calls for a decolonised climate narrative are necessary; however, neglecting or, even worse, deliberately ignoring the role of faith sidelines the discourses among the faith communities most affected by climate change. Insofar as high-level policy conversations remain strictly secular, they merely manifest the exclusionary, Northern-centric narratives which the climate justice movement seeks to disrupt. Adopting overly technocratic political jargon when discussing climate solutions — think concepts like ‘mitigation’, ‘adaptation’ and ‘Net Zero’ — often fails to resonate with faith communities living in the Global South. Through our work at the LSE Religion and Global Society Unit this year – which has included an interfaith climate workshop for grassroots community leaders and religious figures in Cairo – the impact of centring spirituality and scriptural reasoning in discussions of climate change with these communities has become clear. Engaging in such a faith-centred process can, in the words of my colleague Cameron Howes, lead to ‘a greater willingness [in these communities] to engage with the secular and scientific discourse’ of climate change and navigate the vulnerability and precarity of climate change in their daily lives ‘without paralysis’.

The global climate crisis might seem like a crisis of the future. In many parts of the world, however, discussions about ecological justice and equitable climate solutions emerge from present experiences of a changing climate. In ensuing discussions, faith can – and often does – provide a helpful lens through which to make sense of a changing climate and motivate climate action.

Substantive progress in slowing global warming and codifying climate justice into international agreements depends on the extent to which the experiences of faith communities in the Global South are centred in political discussions and delegations internalise a key message: when discussing nature, neither God nor local communities can be ignored.

In his functional capacity as head of state, spiritual leader, and asset manager, Pope Francis is uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between faith communities and global institutions within the climate space. In this regard, he may have been – and perhaps still will be – the most influential figure at COP28.

This is one the most interesting blogs I’ve read. I’m from Pakistan, where religious zeal often clouds judgement in policy making. Most of the times when we’re hit my natural disasters, especially floods and earthquakes, the religious community blames it on the ‘immodesty’ in our society which is hilarious at best and psychotic at worse. I’d be interested to know more about how religious clerics in developing countries can educate people on climate change. For instance, when Iran wanted to tackle its population problem, it used religious clerics to talk about birth control in mosques at the Friday sermons and it worked. Would love to know your thoughts on this.