When were the ‘founding fathers’ of Sociology first taught at LSE’s Department of Sociology? Reflecting on his work as Graduate Teaching Assistant, Matt Reynolds delves into the School’s archives to show how slowly the ‘sociological canon’ developed and considers how it might change in the future.

Over the last two years I have had the pleasure of working as a Graduate Teaching Assistant here in the department, most recently on the second-year undergraduate course SO201 Key Concepts: Advanced Social Theory. One unit introduced the question of what it means to ‘decolonise’ along with how Gurminder Bhambra, Julian Go and others think sociologists should fight epistemic injustice. As I was preparing for this class I decided to zoom in on an institution that all my students knew, LSE. I presented them with some information asking: how did the sociological canon change at LSE over time, and what should it be in the future?

Which theorists were taught in LSE Sociology in the past?

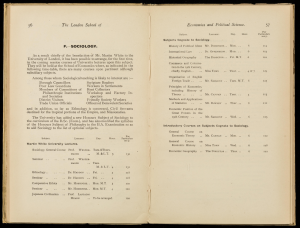

My starting point was LSE’s archive of ‘calendars’ showing who taught what from its founding in 1895 up to the 21st century (available in the library and online here). Sociology did not appear until 1904-5 and the earliest documents do not include reading lists, but we already find clues of the era’s prevailing ideology; the course was “likely to interest”, among others, “Civil Servants destined for the tropical portions of the Empire and Missionaries”.

LSE Calendar, 1904-5, showing potential professions the degree could lead to, what courses were taught and by whom. LSE Digital Library.

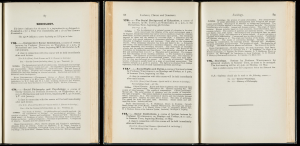

In the 1910s and 1920s the catalogues began to specify the “books recommended” for students to read, and it is striking how few of Sociology’s so-called ‘founding fathers’ appear. None of my students had heard of Edvard Westermarck, Leonard Hobhouse or Morris Ginsberg, even though they founded LSE’s Department of Sociology, The Sociological Review journal and the British Sociological Association. However, when I showed my class examples of the books they had written (e.g. The Material Culture and Social Institutions of The Simpler Peoples and The History of Human Marriage) with their distinctions between ‘savage’ and ‘civilised’ cultures, they did not regret their exclusion from the curriculum in 2023. One name from these early years that they were familiar with was Émile Durkheim. During their first year “Introduction to Social Theory” course they critically analysed his influential theories of organic and mechanical solidarity, along with his problematic ideas on ‘primitive people’ and women. A more surprising name in the early curricula was Peter Kropotkin, whose theory of ‘mutual aid’ ran counter to Herbert Spencer’s ‘survival of the fittest’, the Social Darwinist justification for colonial domination. Durkheim remains a canonical figure today while Kropotkin dropped off the course by 1930, but it is interesting to see that an anarchist voice was given a platform within a university explicitly preparing people for a colonial career.

LSE Calendar, 1921-22, with ‘books recommended’ by Westermarck, Hobhouse, Ginsberg, Durkheim, and Kropotkin. LSE Digital Library.

How did the sociological canon change in LSE Sociology over time?

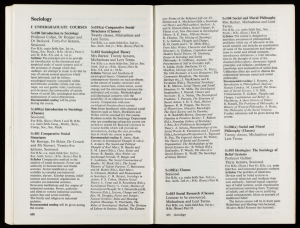

Westermarck and Hobhouse faded in significance over the course of the 20th century, though the latter still lends his name to a prize for the best master’s dissertation. One of Ginsberg’s textbooks remained on the reading list until the late 1970s, but by this point today’s ‘founding fathers’ were dominant; “familiarity with classical social theorists such as Marx, Durkheim and Weber” was a prerequisite for a course in 1976-77. This canon took a while to establish itself; Durkheim was joined by Weber in 1932 and by Marx in 1948 (though he had been studied in political and economic history since the School opened).

LSE Calendar, 1976-77, where ‘familiarity with Marx, Durkheim and Weber’ is assumed knowledge by second year. Copyright (c) London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) Source: LSE Digital Library.

It took until 2011 for W.E.B. Du Bois to take his place as the final ‘founding father’ on LSE’s Introduction to Social Theory and the department has been enriched as a result. In the wake of the First World War, Du Bois encapsulated European hypocrisy by stating that “What Belgium now suffers is not half, not even a tenth, of what she has done to black Congo.” My students drew parallels between this and contemporary nation states making foreign policy decisions at odds with the human rights they claim to respect. In class discussion, they appreciated that they were now being taught about figures like Du Bois but remained frustrated that the sociological canon remained both Global North-focused and male-centric. In addition to looking forward, to the diverse contemporary sociologists taught by our department, we can also benefit by looking back at what we have lost along the way. Looking over LSE calendars from the 1930s, female scholars like Margaret Mead and Marianne Weber appear fleetingly, along with the Indian sociologist G. S. Ghurye. His 1932 book, Caste and Race in India, shows the insights we have missed, how caste is valuable to study both on its own terms and as a “marked contrast to the social grouping prevalent in Europe or America.”

What will the sociological canon look like in the future?

When I asked my students to imagine that they were in charge of who made up the sociological canon, there was no clear consensus on the way forward. Some wanted a radical change to the white, Global North, and male canonical figures, such as dropping Durkheim altogether. Other students were wary, responding with counterarguments like – “how can we understand Western domination without understanding the social theory underpinning it?” and, “how can we understand Black Marxist Feminists like Angela Davis without first understanding Marx?” As class teacher I did not contribute my own opinion, but the discussion stayed with me. I started to feel that leaving Émile Durkheim as the sole survivor of the early curriculum had turned him into a scapegoat for the discipline’s other founders and their colonialist theories. Not only is it important for institutions to be transparent about their own history, but key texts like Said’s Orientalism and Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth hold even greater significance when considered against works like The Material Culture and Social Institutions of The Simpler Peoples.

My students’ critique of the gender balance is also vital when considering that adding Du Bois to Marx, Durkheim and Weber still results in a sociological canon of four men. In my own PhD research on domestic workers in wealthy households, I draw upon the theory of a neglected founding mother of sociology, Harriet Martineau, who I learned about from lecturers during my MSc here in the department. Martineau wrote the ethnographic manual How to Observe Morals and Manners decades before Durkheim’s Rules of Sociological Method. Furthermore, most ‘classical’ sociological texts come from the 19th and early 20th century. As a previous post on this blog highlighted, we could go even further back to Ibn Khaldun from 14th-century Tunisia to find Sociology’s roots. Marx was added to the sociological canon in the 1940s, and Du Bois only recently. When can we expect the next new entrant? In order to achieve epistemic justice, perhaps the whole concept of a ‘canon’ has outlived its usefulness.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of the Department of Sociology, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Copyright (c) London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) Source: LSE Digital Library.

Fascinating and very well written survey.

Interesting that Beatrice Webb never seems to have featured, given her interests in sociological theory and qualitative methods – and her debates with Herbert Spencer, who was a great friend and mentor but whose ideas she ultimately rejected.

Very insightful article. I also realized that SO100 included mainly male sociologists but found it hard to exclude any of them from such an INTRO level class.

Great approach to teaching students how to access archives and practice sociological reflexivity! It could be even more fascinating to break down the narrative of a monolithic global south. Ghurye’s work although looked at castes and tribes in India, it was a particularly Hindu nationalist approach. Tribes were only Hindu sects that were yet to catch up with the rest of the country. Despite many tribes and castes in India distancing themselves from Hinduism, Ghurye insisted on their Hindu origins.