“With governments and economic powers eager to get back into gear through “new normal” narratives, existing social inequalities and environmental issues would remain unsolved. They would also affect the spaces of citizens’ collective actions, which need to continue evolving to sustain the momentum”, writes Dr Rita Padawangi, Senior Lecturer at Singapore University of Social Sciences.

_______________________________________________

Developments of infrastructures and quarantine systems, which eventually became the norm after historic pandemics, were the “new normal” when they were introduced post-pandemic. Past pandemics have shaped modern cities through their infrastructures, such as the modern sewerage system introduced in response to the cholera outbreaks in the 1800s. “Quarantine” systems were developed in response to the Black Death (Yersina pestis) plague in the 14th century. Recently, many governments are using the term “new normal” to reflect the behavioural and regulatory adjustments to minimise the spread of COVID-19 while returning to regular activities. Many are hoping for a vaccine or medication, much like how Yersina pestis is subsequently treated with antibiotics and influenza with seasonal flu vaccines. This “new normal” and hopes for a vaccine or medication come with assumptions that the world needs to go back to “normal” business as soon as possible. However, the “normal” has proven to be problematic, as it has caused social inequalities and environmental degradation that eventually contribute to causing pandemics.

Urban developments around the world have normalised social inequalities for a long time. Normalcy implies a society in which existing social inequalities, discrimination, and even oppression are justified or blindsided in the name of “progress”. Laura Spinney, author of The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World, wrote that we all have a role to play in creating this new virus. Urbanisation, as the engine of economic growth, has taken up fertile lands, rice fields, and forests to build roads, airports, houses, condominiums, new towns, and extract natural resources through mining. These urban spaces that are developed to attract more investments often rely on crowding people in high density to maximise profit, and at the same time limit human choice to maintain distance. In the process, these developments not only increase the likelihood of the occurrence of zoonoses — infectious diseases caused by viruses that jump from non-human to human hosts, such as SARS-CoV2 — but also decrease spaces for various communities, such as farmers, fisherfolks, adat (traditional) societies, who become the collaterals of development. Collaterals of development include everyone who is in the margins, such as the urban poor, who are often subjected to forced evictions. Along with the razing of spaces in the margins of development, spaces of cultural practices also become more limited.

Social inequalities that have been normalised in business-as-usual times are exposed during this pandemic. For example, in the first month after the first COVID-19 case was identified in Singapore, the city-state had won worldwide praise for curbing the level of infection, only to see it spike tremendously at the end of March 2020. During the first month, the response measures missed migrant workers who live in dormitories. Many of these workers construct buildings in Singapore, but where they live is segregated from the rest of the population. Once the virus reached the dormitories, dense living conditions did not allow room for physical distancing, and by the end of June 2020 there had been more than 40,000 COVID-19 cases among migrant workers who live in dormitories. Currently, there are interventions to temporarily rehouse healthy workers to reduce density, but the infections have spread. There was also panic-buying in Singapore’s supermarkets in the early days of the virus spread, which indicates perceptions of its insecurity when functioning in a crisis.

Given many problems that have been normalised in the “normal”, there is a need to question “normalcy” by rethinking urbanisation. To do so, seeing beyond state interventions is important to examine possible alternatives. In many countries of Southeast Asia, perhaps with the exception of Singapore, the state has limitations in controlling many aspects of citizens’ everyday experiences. There have been manifestations of these limitations in various urban landscapes, for master plans by state technocrats are often mismatched with realities on the ground. Given the relative limitations of state control, civil societies are important actors to observe in Southeast Asia’s dynamics in their daily lives as well as in extreme events. Civil society groups in Southeast Asia have also evolved to transcend national territories, such as the Community Architects Network. In recent experiences of disasters, whether typhoons in the Philippines or earthquakes in Indonesia, there have been obvious roles for civil society groups and networks to collaborate to deliver aid and empowerment programmes in disaster-hit areas.

COVID-19 is the first pandemic in the era of these increasingly interconnected networks. How have civil society groups responded to the pandemic? What are their limitations? What can we learn from Southeast Asia’s civil societies in questioning normalcy in today’s urban development? In answering these questions, I would like to focus specifically on citizens’ collective action as an important phenomenon in this pandemic. Southeast Asia is a region in which these collective responses have emerged, activated through existing networks of civil society groups and citizens. From self-imposed area quarantines to food sharing and crowdfunding and collective farming, there is evidence that societies that are socially and culturally active have the potential to be more resilient.

Firstly, it is necessary to look into actions on the ground to understand emerging patterns. In Southeast Asia, state control is usually limited in governing everyday lives. Hence, various neighbuorhoods have collectively acted to respond to the pandemic. For example, an urban poor neighbourhood in north Jakarta, Kampung Akuarium, started to impose neighbourhood movement restrictions as early as 9 March, before the city’s official restrictions (Figure 1). Subsequently, residents built a portal and assigned shifts among themselves to guard the checkpoint. There have been plenty other examples across cities and in villages, from collective guarding, movement restrictions, to disinfecting public spaces in the neighbourhood.

Another example of collective action on the ground is the effort to have an alternative supply chain. There have been individual initiatives to grow edible plants, but we’ve also seen expansions of collective urban farms. One of the examples is the newly-formed Serikat Tani Kota Semarang (Semarang City Farmers Collective) in Indonesia, in which citizens start a group to cultivate on unused land to challenge existing food supply system. The pandemic is a reminder about the unsustainability of current food supply chain to urbanising areas.

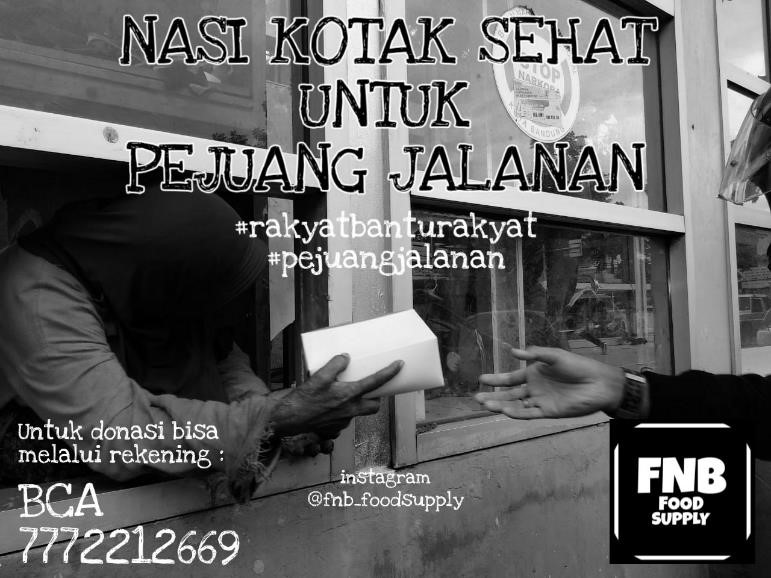

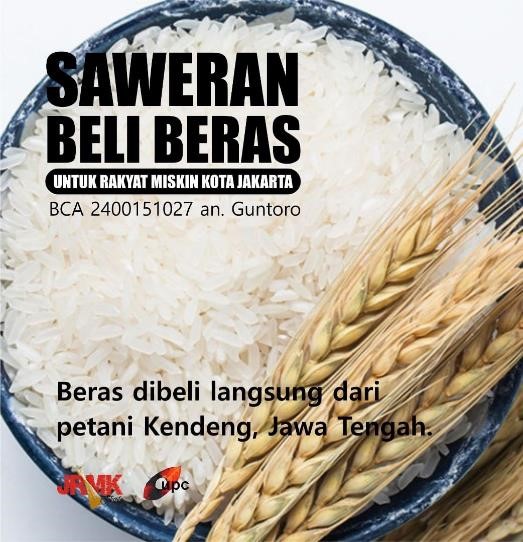

Secondly, citizens’ networks of aid are important. Citizens’ networks operate peer-to-peer to channel resources from one point to another. In Indonesia, there are food distribution initiatives by punk youths from Bandung and Bali (Figure 2). In various places in Southeast Asia, particularly where governments do not intervene and corporations’ activities have slowed down, existing networks channel food resources from the countryside. An example is a crowdfunding initiative to buy rice from cement factory-threatened farmers in Central Java, Indonesia, to be sent to the urban poor in Jakarta (Figure 3). Bursts in crowdfunding initiatives in the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore during the pandemic are interesting phenomena.

Through these initiatives, the state’s incapacity is further highlighted. It is, however, fair to question the sustainability of these initiatives. In the words of Nathalie Dagmang, one of the activists in Manila: “It feels frustrating knowing that what we were doing was still inefficient and unsustainable. The government has all the resources, communication channels, control over transportation, and the personnel for checkpoints and local units. They are the ones mandated, by virtue of our votes and taxes, to provide for our needs during calamities such as this. But where are they now?” Therefore, it is important for these actions to evolve into a structured societal alternative.

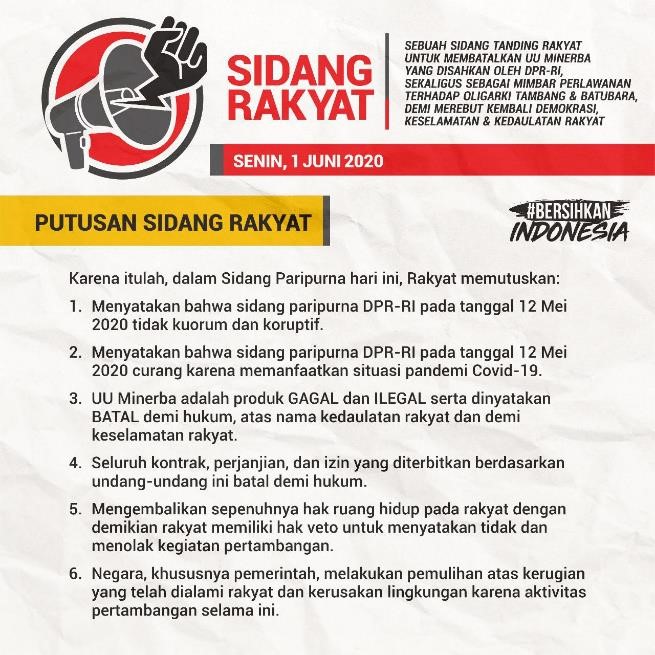

Thirdly, the pandemic has catalysed the appropriation of technology as public sphere. This is not new, and on one hand, many have highlighted the problems of over-reliance on information technology to communicate in the era of physical distancing. These problems echo the larger social inequality. On the other hand, the pandemic had pushed activist networks to exploit these communication technologies, to open up discussions through cyber spaces more intensively than before. Kampung Akuarium, the neighbourhood in Jakarta previously mentioned, could continue their ongoing land reform process through online meetings with government officials. The online public sphere has also shown possibilities to conduct online protests and various discussions, on topics including environmental sustainability, critical thinking on urbanisation-as-usual, and distribution of land and agrarian reform (Figure 4).

Besides technologically mediated public spheres, there are also newly emerging civic spaces. The Semarang City Farmers Collective in Semarang, mentioned earlier, has held training to question capitalist development, along with critical topics such as agrarian social movements, feminism and ecology, along with basic techniques of farming and food processing. In this case, COVID-19 exposed the failures of capitalist urbanisation, and these groups started forming and expanding small civic spaces. As the group is still new, its sustainability remains to be seen, but the phenomenon remains important to observe.

These observations on collective action initiatives reflect an awareness of the need to rethink the usual priorities in the urbanisation process. “Cities as engines of economic growth”, a paradigm that pushes for more urbanisation, has reduced fertile land to produce food, but the pandemic has been a reminder of the importance of food security. A case in point is Singapore, which used to be an agricultural society, but became 100% urbanised and the place with the highest per capita income in Southeast Asia. But it achieved those economic developments by pushing agriculture out. Farming now only counts for 1% of the land.

Other countries in Southeast Asia present different cases when it comes to urbanisation and food production. In the largest country in the region, Indonesia, food production has been a part of many societies’ cultural practices. Nevertheless, the normalised urban-biased developments have obscured this part. Traditional fisherfolk in Jakarta Bay, for example, have been sidelined for real estate-driven reclamation projects. Java, the most populated island in the Indonesian archipelago, is a very fertile island, but it is now the most industrialised, and more and more land is being taken for non-agricultural uses. Even in a place like Bali, where agriculture remains tied with everyday life, the share of agriculture in the province’s economy has continued to decline, as opposed to the share of tourism-related trade and services that continue to grow. Before the pandemic, many saw global tourism as “good” for the economy, yet it threatens the sustainability of subak — the traditional water management system for irrigation that has been around for more than 1000 years — as agricultural land use had to compete with tourism. Such dependency on global tourism has become the Achilles heel of the economy in the pandemic, as tourism and the entertainment industry have ground to a halt. But the cultural villages (banjars) that are still in agriculture can continue to produce food, and the banjars’ societal structure had been credited as effective in curbing the spread of the virus.

At the heart of resilience in this pandemic is the force of local communities, collective action, to break free from the “normal” supply chain, the “normal” competitive economy, the “normal” obsession with skyscrapers and buildings. The ability to collectively act to function autonomously — socially, economically, and culturally — in the local context forms the basis of resilience. Many of these actions go back to simple gestures of social relationships and the natural environment, and to making economies relevant to the everyday life of the land rather than pushing for an economic development that is predatory to existing resilience.

Today, as countries are eager to revive their economies, the “new normal” has been popularized as a term for a situation that adapts to life with the virus as a given reality while minimising its spread as much as possible. However, the problem with the term “new normal” is that urban-biased assumptions play into it so much that many are trying to replicate “normalcy” as close as possible. In an interview with The Guardian, Richard Sennett expressed concern about the possibility of imposing social-physical distancing on development policies; social-physical distance in development would result in increasing building footprints and would contradict efforts to fight climate change. Furthermore, such sprawling development would result in new developmental collaterals — and the marginalised groups would be the first in line. There are also worrying tendencies in Southeast Asia that suggest the pandemic may shrink civic spaces, as there are restrictions on public gatherings, cuts in funding for democracy and human rights advocacies, movement restrictions, and further limitations on freedom of speech. These restrictions are often imposed in the name of preventing the virus’s spread, but they are also being used as tools of repression.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a moment in which collective action could demonstrate alternatives to “normal” urbanisation through actions on the ground, activation of networks, as well as intensification of the public sphere through online platforms. However, the sustainability of these alternatives is also affected by the availability of space, resources, and time. With governments and economic powers eager to get back into gear through “new normal” narratives, existing social inequalities and environmental issues would remain unsolved. They would also affect the spaces of citizens’ collective actions, which need to continue evolving to sustain the momentum.

*This blog is based on Dr Padawangi’s talk delivered at the LSE Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre’s online event on 3rd June 2020 entitled, “Post COVID-19 Futures of the Urbanising World”. Watch the recording of the event here.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.