“Despite being the backbone of Malaysia’s business environment, SMEs perform relatively poorly in digitalization. There exists a digital divide among businesses in Malaysia”, write Amos Tong, an economics undergraduate at UCLA, and Rachel Gong, a researcher at the Khazanah Research Institute in Kuala Lumpur.

_______________________________________________

Digitalization is increasingly useful for small and medium enterprises to improve efficiency and competitiveness. We discuss the state of digitalization among SMEs, and businesses more generally, in Malaysia prior to the pandemic. Although the prevailing wisdom is that Covid-19 has ushered in a pivot to digitalization, there remain many challenges that SMEs face in doing so. Government and policy interventions can facilitate this process, and we suggest some steps that can be taken to support SME digitalization.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the enforcement of the Movement Control Order (MCO) in Malaysia[1] resulted in an unprecedented slump in economic activity. In Q2 2020, Malaysia’s GDP contracted by record-setting 17.1% year-on-year. Businesses adopted digital measures to make up for the shortfall in traditional sources of revenue. As more business establishments digitalize[2], firms that are left out of this digital revolution will struggle to survive, let alone thrive.

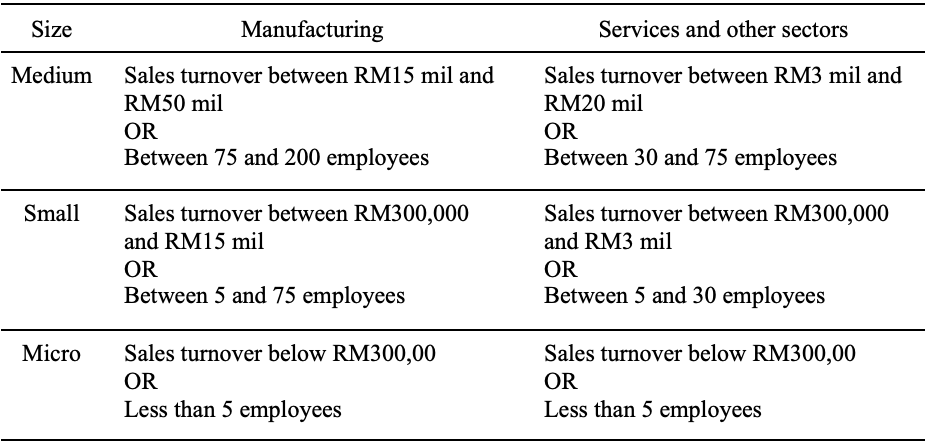

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) make up 99% of the 920,624 business establishments in Malaysia. In 2018, SMEs employed 66.2% of the workforce in Malaysia, contributing RM522.1 billion, or 38.3%, to the Malaysian GDP. They are classified into three categories: micro, small, and medium, defined by industry, sales turnover, and the number of employees. Micro-enterprises make up 76.5% of Malaysian SMEs. In contrast, medium-sized enterprises comprise only 2.3% of SMEs.

Table 1: Definition of small and medium enterprises in Malaysia. SME Corporation Malaysia (2020).

Research (e.g. Connected Commerce Council 2020, Winarsih et al 2020) suggests that SME digitalization is key to their sustainability and was accelerated by the pandemic. We begin by making a case for SME digitalization.

Why SMEs should digitalise?

For large firms, the rationale behind digitalization is clear: digitalization improves efficiency, competitiveness and economies of scale. Firms can use complex technologies such as the automation of production processes and data-driven quality control processes to reduce costs and increase profit margins.

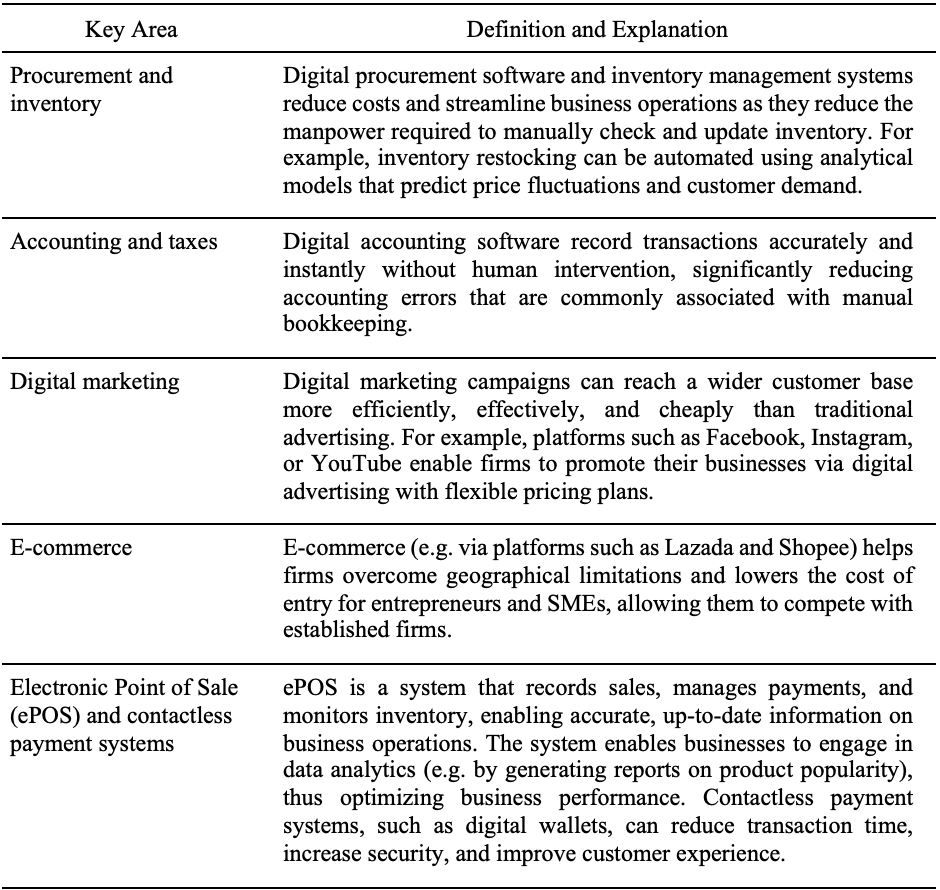

However, the case for digitalization among SMEs is not as clear. Digitalization is perceived as complex, costly, and unnecessary. But digitalization does not necessarily mean expensive equipment and total automation. There are 5 areas of digitalization that benefit firms of all sizes.

Table 2: Key areas for digitalisation. Adapted from Malaysian Digital Economy Corporation (2020)

Contrary to the notion that it is unnecessary for SMEs to digitalize due to their small scale, SMEs stand to benefit massively from adopting digital technologies. A study by the University Consortium of Malaysia found that the use of digital technologies would significantly improve SME productivity. SMEs that used social media experienced a 26% increase in productivity while those that engaged in e-commerce saw productivity increase by 27%. Moreover, the application of advanced digital technologies such as data management solutions could increase SME productivity by up to 60% (Huawei Technologies, 2018).

Pre-COVID state of digitalisation of Malaysian firms

Between 2010 and 2016, Malaysia’s digital economy grew 9% annually in value-added terms; it will make up 20% of the country’s economy by 2020. E-commerce alone is expected to exceed RM110 billion – nearly 40% of the digital economy (World Bank Group, 2018) – in 2020. These figures are impressive, but research and statistics suggest that Malaysian businesses still have room for growth.

Overall, businesses in Malaysia do not adopt digital technologies as readily as the Malaysian government and population. Digital adoption by Malaysian businesses lags behind the global average: only 29% of businesses have a web presence while a meagre 5.2% of businesses engaged in e-commerce in 2015 (World Bank Group, 2018).

Only about one in three businesses in Malaysia have implemented digital transformation strategies, while less than a quarter of businesses have a dedicated digital strategy team. Malaysia also has “fewer businesses with websites, and fewer secure servers than per capita income would predict” (World Bank Group, 2018) compared to other countries.

Despite being the backbone of Malaysia’s business environment, SMEs perform relatively poorly in digitalization. There exists a digital divide among businesses in Malaysia, as SMEs are “less likely than the average business establishment to access and use the internet” while “large export-oriented firms dominate the digital economy as they adopt e-commerce at higher rates than SMEs” (World Bank Group, 2018).

SMEs digitalize primarily in fundamental technologies and not in more complex digital solutions, causing them to lag behind large firms. Although 77% of digitalized businesses are SMEs, only 25% of businesses achieving advanced digitalization are SMEs.

Generally, Malaysian SMEs have increased their use of information and communication technologies, with over 80% of businesses using computers and smartphones, and over 70% using the internet in their business operations in 2018 However, only 46.1% of SMEs used digital finance and accounting systems.

Digital adoption by SMEs is most concentrated in computing devices and connectivity (>85%), and least prevalent in back-end business processes such as inventory management (14%) and order fulfilment software (11%). Furthermore, few SMEs use advanced digital technologies that could significantly boost their business performance. For instance, only 44% and 54% of SMEs use cloud computing and data analytics respectively (Huawei Technologies, 2018). For comparison, in 2014, 85% of SMEs in Singapore used cloud computing.

The biggest challenges to SME digitalization are financing, employee skillset and inadequate technology. Despite government assistance, about 50% of SMEs in Malaysia cite funding as a key hindrance to digitalization, while 60% of SMEs are unaware of their financing options, exacerbating this problem. Only a small proportion of SMEs sought payment restructuring assistance for their internet service during the MCO. Compounding this problem, 44% of SMEs cited broadband issues – high price and low speed – as a key barrier to using cloud services (Huawei Technologies, 2018).

Also, 48% of SMEs cited ill-suited employee skill sets – e.g. the need to develop sales and marketing, business management and IT technical skills among employees – as a major challenge to digitalizing their businesses. Technological expertise is also lacking among employers as many SMEs do not know how and where to digitalize. Lagging SME digitalization pre-COVID has significant implications for SME business performance and survival during the MCO.

Impact of COVID-19

The MCO mandated the temporary closure of non-essential businesses and prohibited mass movements nationwide. Within a week, 70% of SMEs reported a 50% drop in business.

Contrast these figures with those found in the digital space during the same period: online non-food shopping increased by 53%, online grocery shopping by 144%, and online food delivery by 61%. On the first day of the MCO alone, food delivery platforms GrabFood and Foodpanda witnessed a 30% increase in orders. On the back of these trends, the Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC) projected 20% growth for e-commerce in 2020.

The contrasting trajectories between online and offline economic activities indicate that it is crucial for SMEs to participate in the digital economy if they are to survive and succeed in the post-COVID world. The agriculture industry in Cameron Highlands provides a perfect example. During the MCO, farmers were unable to sell their produce due to restrictions on logistics and transportation and had to dump all their produce due to storage constraints. To overcome this problem, farmers turned to e-commerce platforms (e.g. Lazada) and sold 70 tonnes of produce online within 3 weeks.

Besides front-end business processes such as e-commerce, also important is the digitalization of back-end processes such as accounting, administration, communications, data processing and document handling services. During the MCO, 84% of SMEs experienced difficulties with their online connectivity and communications with customers and suppliers. Many SMEs also highlighted poor work-from-home (WFH) connectivity (Ernst & Young, 2020). The low pre-COVID levels of back-end digitalization among SMEs resulted in lower productivity, lower efficiency, and lacklustre business operations during the MCO.

The Malaysian Government has introduced a series of initiatives to encourage SME digitalization. For example, 28 initiatives – predominantly financial aid – under the PRIHATIN Economic Stimulus Package are targeted at SMEs. MDEC also partnered with 237 local tech companies, including network providers, e-commerce platforms, and technology service providers, to offer discounts to incentivize SME digitalization.

Despite these initiatives, only 25% of Malaysian organizations accelerated their digital transformation plans as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, while 60% slowed down. SME digitalization efforts during this crisis are heavily influenced by reduced cashflow. Under tight financial constraints, it is unclear if there is room for significant increases in SME digitalization during the pandemic. While the Government is encouraging SME digitalization, there are underlying challenges that hinder these efforts.

The way forward

Given these challenges, government policies are needed to bridge the digital divide between firms. The goal of these policies is to build an inclusive digital economy that benefits all parties. To achieve this, the Malaysian Government could consider a four-pronged approach:

- Ensure affordable and high-quality digital infrastructure. Public-private partnerships to reduce the price of basic digital infrastructure should be developed and maintained to reduce the financial barriers to SME digitalization. These efforts can be expanded to accelerate the development of affordable, high-quality digital infrastructure and services nationwide.

- Encourage the digitalization of more advanced back-end processes. 72% of SMEs do not know how to automate their business operations while 42% of businesses that are aware of cloud computing services “do not know how to leverage cloud computing to transform their businesses” (Huawei Technologies, 2020). In addition to raising awareness of the benefits of digitalizing back-end processes as described earlier, worker training and upskilling could improve SME employee technical competencies and spur digitalization from within SMEs.

- Engage SMEs regarding the availability of government initiatives and incentives. Many SMEs are likely unaware of government initiatives and incentives for digitalisation. As mentioned earlier, 60% of SMEs that cited funding as a barrier to digitalisation were unaware of their financing options. Further engagement efforts, such as direct outreach to individual SMEs to alert them to skills-based training programmes, for example, could help increase SME digitalisation rates.

- Expand digitalization incentives to all interested SMEs. MDEC runs various programmes to promote SME digitalisation. However, these programmes have some restrictions. For instance, the SME Business Digitalisation Grant is limited to 100,000 SMEs. Admittedly the take up rate of these programmes may be low as many SMEs may be unaware of or uninterested in such programmes. Nonetheless, the Government could expand these programmes to all interested SMEs

SME digitalization is key to their long-term sustainability in an increasingly digital economy, but the digital divide between firms presents tough challenges. Although Covid-19 has accelerated digitalization in general, SMEs are at risk of being left behind. Government and policy interventions will play a crucial role in shaping the future of the Malaysian digital economy.

Footnotes

[1] The MCO began on March 18th 2020 and is scheduled to run until December 31st 2020. It is a government directive that specifies approved mass movement and gatherings in Malaysia, and includes standard operating protocols such as contact tracing, physical distancing, and quarantines.

[2] Digitalization is defined as the process “in which many domains of social life [including businesses] are restructured around digital communication and media infrastructures” (Brennen and Kreiss 2016).

References

Annuar, A. (2020, March 27). Covid-19: After MCO, survey finds nearly 70pc SMEs lost half income. (Malay Mail) Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/03/27/covid-19-after-mco-survey-finds-nearly-70pc-smes-lost-half-income/1850688

Connected Commerce Council. (2020). How digital tools power small businesses amid COVID-19. Retrieved September 14, 2020, from Connected Commerce Council: https://digitallyempowered.connectedcouncil.org

Ernst & Young. (2020). COVID-19: Impact on Malaysian business. Retrieved September 9, 2020, from https://www.ey.com/en_my/take-5-business-alert/covid-19-impact-on-malaysian-businesses

Huawei Technologies. (2018). Accelerating Malaysian Digital SMEs: Escaping the Computerization Trap. Retrieved from https://www.huawei.com/minisite/accelerating-malaysia-digital-smes/img/sme-corp-malaysia-huawei.pdf

Scott Brennan, D. K. (2016). Digitalisation. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy.

Kaur, M. (2020, April 16). Farmers stop dumping veg in Cameron. Retrieved September 8, 2020, from The Star: https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/04/16/farmers-stop-dumping-veg-in-camerons

Malek, N. H. (2020, August 12). Covid-19 accelerated the business digitalisation process. Retrieved September 10, 2020, from The Malaysian Reserve: https://themalaysianreserve.com/2020/08/12/covid-19-accelerated-the-business-digitalisation-process/

Ministry of Communications and Multimedia Malaysia. (2020, August 11). Bernama : 11 Aug 2020 : COVID-19 shows importance of digitalisation for SMEs, says MDEC. Retrieved September 2, 2020, from https://www.kkmm.gov.my/en/public/latest-news/17535-bernama-11-ogos-2020-covid-19-shows-importance-of-digitalisation-for-smes-says-mdec

SME Corporation Malaysia. (2020). SME Annual Report 2018/2019.” National Entrepreneur And SME Development Council (NESDC). Retrieved September 3, 2020, from https://www.smecorp.gov.my/images/SMEAR/SMEAR2018_2019/final/english/SME%20AR%20-%20English%20-%20All%20Chapter%20Final%2024Jan2020.pdf

SME Corporation Malaysia. (2020). SME Definition. Retrieved September 7, 2020, from https://www.smecorp.gov.my/index.php/en/policies/2020-02-11-08-01-24/sme-definition

Winarsih, M. I. (2021). Impact of Covid-19 on Digital Transformation and Sustainability in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A Conceptual Framework. Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems. CISIS 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 1194(Springer, Cham).

World Bank Group. (2018, 2018). Malaysia’s Digital Economy: A New Driver of Development. Retrieved September 2, 2020, from https://www.kkmm.gov.my/pdf/KPI/Laporan%207.pdf

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

* An expanded version of this discussion was previously published under the title, “Digitalisation of firms: Challenges in the digital economy”.

4 Comments