“Bringing together different disciplines and stakeholders to work at the intersections of these disciplinary boundaries will bear fruit towards understanding the role digital innovations can play in tackling tropical land use change and other critical global challenges”, writes Dr Rory Padfield (Lecturer in Sustainability & Business in the School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds)

_______________________________________________

Dr Rory Padfield is speaking at LSE Southeast Asia Week 2020

In the last decade, a proliferation of digital technologies and geospatial tools have breathed life into societal understanding of tropical land use change. Drones, satellites, GIS software, digital sensors and various software innovations have all been used to document the nature and scale of deforestation, resource extraction, fires, and landscape transformation, more broadly.

Moreover, the emergence of the internet and wide accessibility of smart phone technology have facilitated circulation of digital outputs from these innovations, whilst strengthening networks of interested citizens and groups via social media platforms. In all, digital innovations have the potential to facilitate a wider and deeper connection between humans and their environments. This blog briefly considers the use of these types of digital innovations in a Southeast Asian context and argues for the need for an interdisciplinary research approach to further develop this emerging knowledge domain.

Before engaging with any kind of technology discourse in the context of tropical land use change, it is first helpful to establish a sense of scale and perspective. Landscapes in Southeast Asia – as with many of the parts of the planet – have been subject to considerable change. Dating back to early colonial extraction of resources and land use clearance for commercial plantations and urban development, forest losses in this region remain a characteristic of development.

Tropical rainforests perform critical ecosystems services, such as climate change mitigation, as well as containing habitats for important flora and fauna. Critically, these sites are also critical for the livelihoods of many communities too. Huge numbers of smallholder farmers, for instance, rely on the income from subsistence and commercial crops grown on these soils. Thus, the question is not to halt land use change altogether but to identify ways in which it can be done whilst retaining the integrity of the region’s ecosystems.

‘Sense making’ via technology and geo-mapping

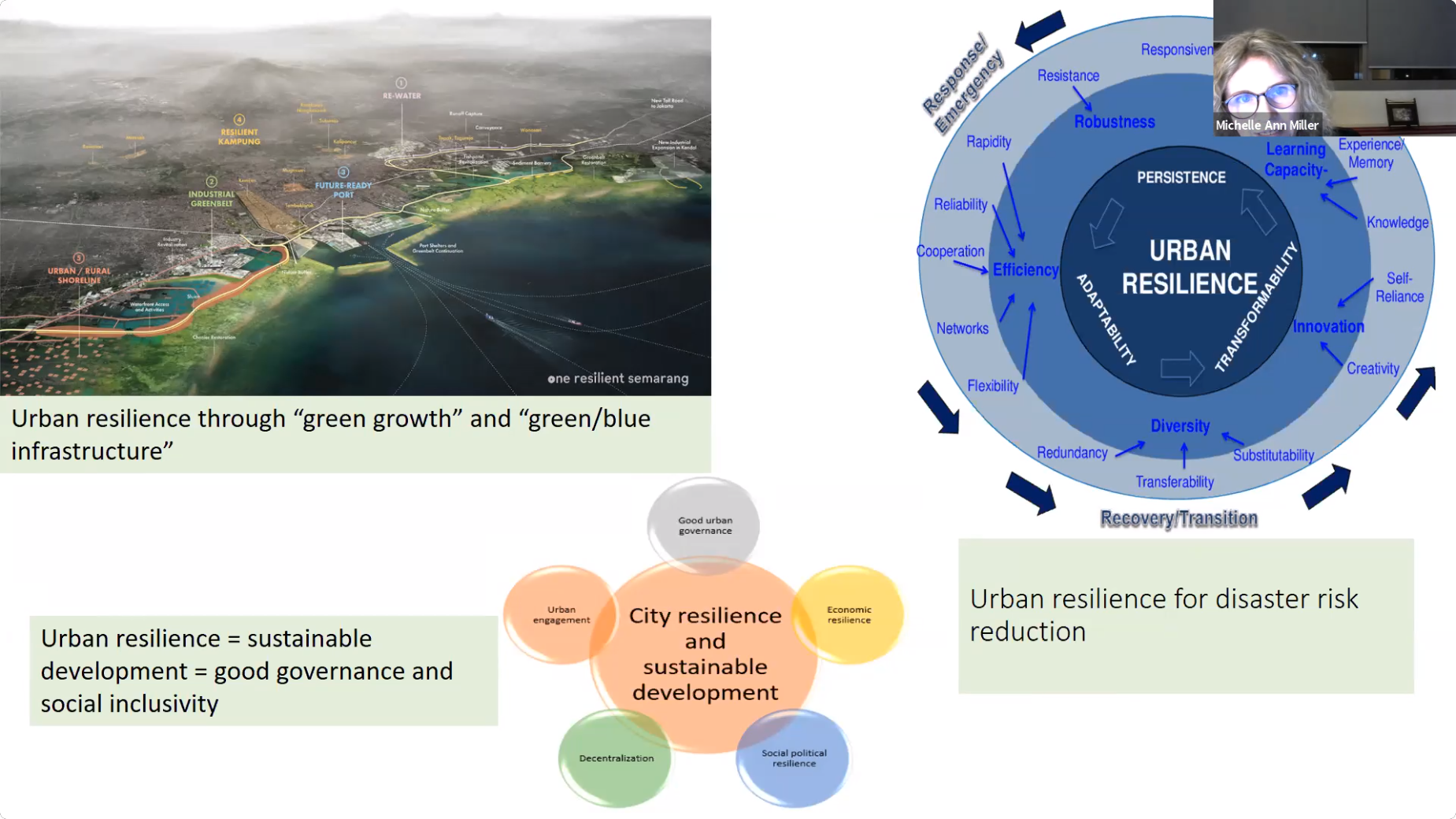

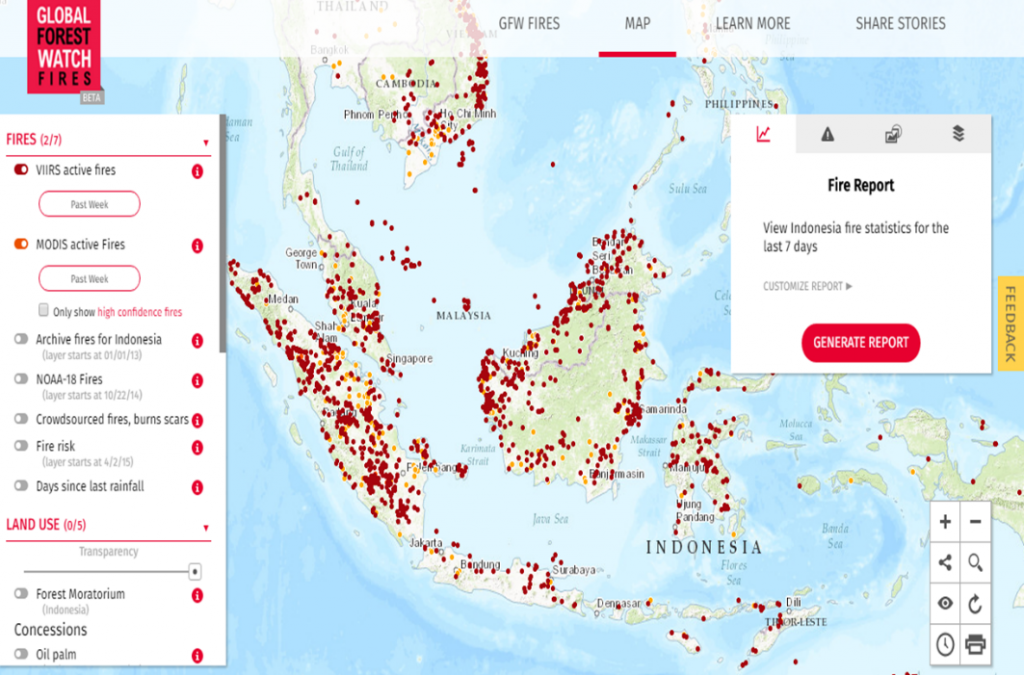

Against a backdrop of national and international policy solutions to tackle tropical land use change, digital technology innovations have become increasingly sophisticated and accessible in making sense of this complex issue. These innovations shine a light on landscape changes taking place in specific geographies over specific periods of time. Examples include the Global Forest Watch’s interactive dashboard (see Figure 1), which overlays satellite data to map forest loss and fire occurrence against land use types and concessions over time.

A whole variety of actors are using these tools to understand the scale and responsibility of landscape change, including corporate actors as a means to map their activities and demonstrate commitment to their sustainability pledges. Importantly, data outputs from these innovations have led to changes in business sourcing strategies and piled pressure on corporations to meet their policy commitments or risk being dropped by buyers in their supply chains.

The broad reach of the internet and 4G/5G digital cellular networks, and smart applications has also facilitated user participation in the sense making of landscape change. Developed by Pulse Lab Jakarta, the Haze Gazer website (Figure 2 below) allows citizens to upload their own content – typically images and short video diaries – in order to share experiences of haze in their communities. In addition to satellite and GIS mapping outputs, social media content is also fed into the website in order to showcase a diverse range of experiences related to haze.

Citizens affected by landscape change in Southeast Asia, such as periodic haze events following burning of peat soils, have mobilised themselves via social media platforms. Users of Facebook, Twitter and other social media platforms share and discuss the digital outputs and resources from the innovations. Individuals and groups draw on these digital outputs as compelling evidence in their advocacy and policy change endeavours. For example, the People’s Movement to Stop Haze have used their collective organisation and knowledge gathered from various digital tools with the aim to influence government and corporate policy related to transboundary haze. Geography thus becomes central; not just in the spatial sense but in the way that through these technologies citizens can better participate in and shape the way their landscapes are managed.

But, for all the good news stories, we must not lose sight of how these technologies can be used or manipulated for less constructive outcomes. Technologies with the power to reveal high granular level data on landscapes use and type pinpoint new and available resources for development. This issue is especially acute where local communities with relatively weak claims to land tenure face challenges from well organised and persuasive corporate actors. Furthermore, we should be mindful that improved digital connectivity does not mean constructive action is taken; we may have greater knowledge on the details of landscape change but it is a different matter to put this knowledge to good use.

Positive value of interdisciplinary research

While digital innovations have a growing role to play in supporting the sustainability and environmental resilience agenda in the context of Southeast Asian landscape transitions, a number of critical questions remain. What are the motivations and outcomes for enhanced digital knowledge and capacity by corporate players? In what way can digital innovations support existing yet fragmented supply chain and sector-wide policy efforts? How can citizen participation be elevated further in these types of innovations? And what is the role of digital and social media more broadly in shaping land use policy and practice? All of these questions need careful and considerate research in view of the potential – both positive and negative – of these technologies in the context of Southeast Asian landscape change.

Lastly, the interdisciplinary nature of this issue – crossing disciplines such as computer and data science to critical social science, humanities and business – requires innovation in the way we study this particular topic. Methodological developments are critical and require researchers to work outside of their comfort zones. New approaches include collaborating with scientists from different disciplines, incorporating new analytical skills and approaches to study, and engaging with non-academic actors, such as technology companies and community groups. Bringing together different disciplines and stakeholders to work at the intersections of these disciplinary boundaries will bear fruit towards understanding the role digital innovations can play in tackling tropical land use change and other critical global challenges.

* This post is based on Dr Rory Padfield’s roundtable intervention delivered on 30th October 2020 as part of SEAC Southeast Asia Week 2020. You can access a recording of the “Environmental Resilience and Southeast Asia” roundtable here.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.