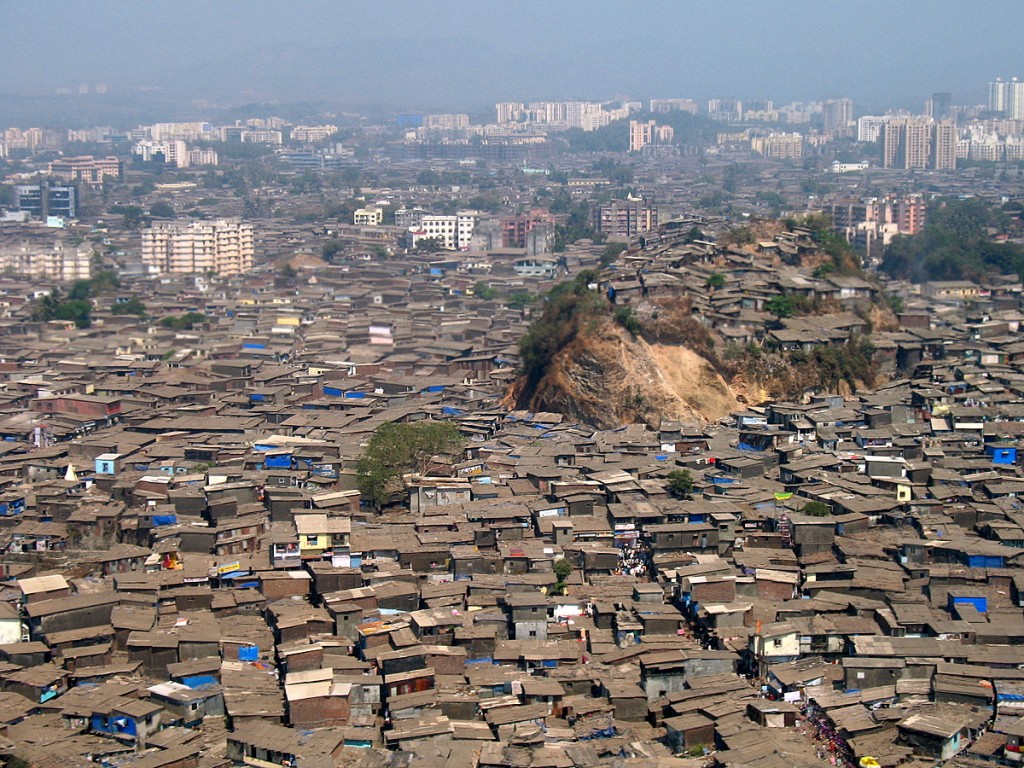

Amitabh Kundu argues that the vision of slum-free Indian cities is hampered by big city bias and the failure to prescribe a framework for identifying non-tenable slums and legitimate slum households that must not be evicted.

The vision of a slum-free India was advanced through the launch of Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) in the eleventh Five Year Plan. A major flagship programme of the present government, RAY seeks to enable poor urban families to realise their dreams of home ownership, with a proper land title and access to basic civic amenities. Granting full property rights to slum dwellers and enacting state legislations in this regard are mandatory requirements under RAY, except in regions with control and ownership of land by the community. However, a big city bias, poor planning, and the failure to standardise criteria for implementation have hampered the programme’s efficacy and reach. Cities must now be encouraged to review the system.

Under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), launched during the tenth Five Year Plan, and now under RAY, small and medium towns have consistently been excluded from plans for improving and allocating urban infrastructure, despite clear evidence of there being a higher incidence of poverty and slum-like conditions than in large cities. The emphasis on large cities – evidenced also by the fact that the Census only collected information on slums in larger cities until 2001 – in the drive for a slum-free India results from the country’s political economy, which necessitates an improvement in the environmental conditions of big cities to make them more attractive for business.

RAY emphasises in situ development, rather than slum relocation, and recognises the importance of land tenure security in the context of the first component of the Slum-free Plan of Action to be prepared at state and city levels. Since land availability is critical for developing housing for the poor, central funds are made available only to the states and cities that can provide land with property rights. This was previously considered necessary under Basic Services for the Urban Poor (BSUP) and Integrated Housing, the JNNURM components for large and small cites, respectively. In sharp contrast to BSUP, under which nearly 40 per cent of slum households were relocated, RAY has prescribed a 10 per cent limit on slum relocation. While in situ development is welcome, this figure needs to be based on realistic assessments of slum tenability and slum population eligibility for housing under RAY and implemented firmly.

Currently under the programme, cities have the responsibility for determining the tenability of slums and identifying them as either ‘hazardous’ or ‘objectionable’ for the purposes of the Action Plan. While hazardous slums are defined in terms of environmental problems and health risks, objectionable slums are those that violate legal or master plan norms. In some cases, only a part of a slum may be identified as tenable or non-hazardous. Unfortunately, there is no clear process or criterion to categorise untenable and hazardous slums, and decisions are taken on a case-by-case basis. Further confusion results from the fact that policies on water bodies, industrial and commercial land, mixed land use, etc. are not transparent or consistent across agencies. This ad hoc system has created enormous conflicts at the local level, often leading to legal impasse.

RAY guidelines must be more specific about slum mapping and granting land titles so that cities and states do not interpret these differently. To prevent subsidy leakages, the programme must identify and target the right beneficiaries; however, city commissioners find these responsibilities taxing in the absence of unambiguous criteria. India’s National Advisory Council (NAC) recommends that the District Collector should undertake slum mapping and surveys of eligible candidates in conjunction with officials, slum residents, youth groups, social workers, etc. For example, state and local government agencies in Mumbai had worked with the Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), an NGO, to develop multiple parameters to determine household eligibility for subsidised housing (with the provision of appeal by the excluded households) and this was a successful experiment.

Click here for Part 2 of this post, which analyses the affordability of the minimum acceptable dwelling unit for slum residents, will be published on Friday, October 26.

Dr Amitabh Kundu is Professor of Economics at the Centre for the Study of Regional Development at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. In 2007, Dr Kundu contributed an essay on ‘The Future of Indian Cities’ to an LSE Cities conference newspaper titled ‘Urban India: Understanding the Maximum City’.

Plzz VOTE for our proposed solution of improving civic amenities in urban india…

http://indiancag.org/manthan/entry/futureleaders

The Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) is a solution in the wrong direction. It will, and it seems it already is doing so as is described in this news article, create more problems than it solves. The solution lies not in accommodating immigrant populations in cities but in creating livelihood opportunities for them in their own villages and small towns so that they may want to go back to where they came from. This done, schemes like RAY can be rolled out to create affordable housing for native born population of the city so that they do not have to set up a shack when they need a place to live and so spring a new slum.