In the second of this two part series, Manisha Priyam analyses how realising the right to schooling is a struggle for Bihar’s poor children, particularly in the face of elite capture of state institutions. She calls for systematic attention to policy implementation to enable India’s poor to claim entitlements and prevent tragedies such as the death of 23 children after they consumed a school lunch served under India’s flagship mid-day meal scheme. Click here for part one.

Although the mid-day meal tragedy in Gandaman has dominated headlines in recent weeks, there is ample evidence in nearby villages that the incumbent government’s efforts to develop infrastructure and schooling in Bihar are working. In village Kewatiya, Dariyapur block of Chapra, I met some young ones en route to school. While the children were aware of the tragedy in Gandaman, they were not deterred from attending school. One student, Manish Kumar, told me, “We know children have died in some village in Mashrakh, but our school is not closed. We will study … but we will not eat a meal in school.” The students showed me the polythene bag with rotis they are carrying to school for lunch.

A little further down the road, I met a group of young girls cycling to the Rajakiya Inter College in Amnaur, where they are scheduled to sit examinations in science and maths. Later, I saw a group of young girls walking to the Buniyaadi Vidyalay Nautan in government-issued school uniforms. Money for the bicycles and school uniforms was delivered directly to the beneficiaries’ bank accounts as a cash transfer, and the girls I met confirmed it reached them promptly without any hassle. These are policy innovations, akin to conditional cash transfers widely used in Latin American countries, seeking to improve enrolment rates in Bihar.

Data showing improved rates of school participation since 2004-05 indicates that state initiatives have enabled more poor children, including girls and those belonging to the most vulnerable social castes, to attend school. This is significant given that primary school participation declined in 1999-2000 despite long-term federal assistance starting in the early 1990s, including external aid from UNICEF for the Bihar Education Project, and from the World Bank for the District Primary Education Programme. Only 51 per cent of primary school age children (6-10 years) were in school in 1999-2000—four percentage points lower than participation rates in 1993-94, as recorded by the National Sample Survey Organisation. In 2007-08, this number improved to a high of 76.1 per cent, primarily owing to outreach among very poor communities.

These gains notwithstanding, insufficient attention has been paid to the local structures of power within which schools operate. Two important aspects of this structure, which development policy must pay special attention to, are the rise of new intermediaries – referred to as naya netas by Anirudh Krishna – and the nature of state-poor relations at the local level, especially viewed through the lens of development schemes on the ground.

In many ways, jailed school principal Meena Devi’s husband, Arjun Rai, fits Krishna’s description of the local influential recast as a new political entrepreneur on the basis of his capacity to access developmental schemes—“the man in the middle … with chains of influence radiating both upward and downward” (p.309). Rai is said to have been influential in getting his wife deputed as the principal of the Gandaman school right across the road from where they live; had control over the sundry purchases for cooking the school meal; and is considered close to influential Yadav politicians. Further, Gandaman residents report the regular pilferage of grains meant for the school mid-day meal. Rai is widely considered to be part of the rent-seeking chain, which diverts school supplies on the basis of collusion with those responsible for transporting grains to schools.

In the policy design, local school councils known as Vidyalay Shiksha Samitis were meant to counter such forces of local domination, but there has been rampant elite capture of these institutions, especially by Panchayat Mukhiyas (see Priyam, 2012). Besides, at the time of the Gandaman tragedy, these councils were functioning in a minimal form, ensuring the domination of the mukhiya and school principal. Although these bodies were compliant with the norms specified under the country’s Right to Education Act, a local analysis of their functioning highlights how technical interventions for community oversight and voice were effectively curbed by local domination.

Gandaman also calls for a closer scrutiny of state-poor relations in terms of how the latter experience the state through its various agencies—the police and the developmental state. Village residents see the institutions of justice – the court in Chapra – as too distant from where they live and beyond their reach. “Whether the death of our children was an accident or a conspiracy, we do not know, and it is for upar ke log (those with power, higher up in the hierarchy) to find out who is to blame,” says Rajesh Sao, a bereaved father.

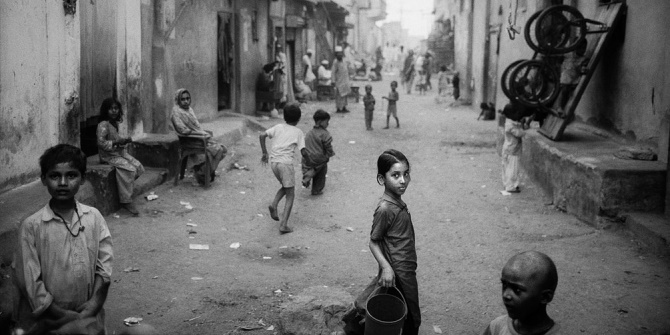

Amidst the grief in Gandaman, I found nobody making an effort (or even expressing a hope) for judicial redress. I asked Shanker Thakur, who lost his eight-year-old daughter, whether he would move the courts. He answered, “I am a poor barber, all I have for a livelihood is this gumti (chair kept by the road-side). What can I do?” Thakur’s lament reminded me of my doctoral research in Baysi in Bihar’s Purnia district, where people complained about the poor quality of mid-day meals replete with crawling insects, but could not lodge an official complaint as nobody would hear them.

Most poor people in Gandaman, and indeed elsewhere in Bihar, see the state “at a distance, episodically, often roughly and through intermediaries” (see Corbridge et al, 2005). It is ironic that Bihar will be using the same channels of distribution and local intermediation responsible for the tragedy in Gandaman to distribute grains to the poor under India’s new food security bill. Pursuing measures of aggregate welfare, while persisting with local structures of hierarchy and exclusion, will unfortunately turn even rights-based state approaches to development into a means for power. Future analysis of failures of policy and implementation must direct itself to understanding the human experience of development, and not limit itself to viewing human development as outcome goals.

About the Author

Manisha Priyam recently completed a doctorate at LSE’s Department for International Development on ‘Politics of Education Policy Reforms in India’. She is currently an ICSSR Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

Manisha is a regular contributor to the India at LSE blog. See here for more posts.

References

S. Corbridge, G. Williams, M. Srivastava, and R. Véron, Seeing the State: Governance and Governmentality in India. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

A. Krishna. “Dealing with a Distant State: The Evolving Nature of Local Politics in India.” Oxford Companion to Politics in India. Ed. Niraja Gopal Jayal and Pratap Bhanu Mehta. Oxford University Press, 2010.

M. Priyam. “Aligning opportunities and interests: The politics of educational reform in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh and Bihar”. PhD thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science, 2012.