Nepal’s local development policymaking regime is undergoing a transformation in order to adjust to the recently established federalist structure in Nepal. Here Thaneshwar Bhusal (Civil Servant and Researcher, Nepal) explains how local policymaking has adapted to the country’s new governance structures.

With the introduction of a federalist constitution in 2015, Nepal aimed at solving three big problems that were supposedly hindering the developmental landscape of the country for centuries. As the preamble of the Constitution writes, the first problem relates to the centuries-old centralized bureaucracy which needed to be transformed in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity. Earlier efforts to reform the bureaucracy brought some changes into the system but they were largely insufficient, if not unsuitable to address the contemporary societal needs. Decentralisation reforms — painted with a greater taste of administrative devolution — took place in a somewhat speedy manner since the early 1980s yet their overall implications to solve the problems of the centralised administrative state were relatively insignificant.

The second perennial problem concerns the socio-economic structure of the country. The Hindiusm-based social structures were found to be creating devastating gaps within societies in the name of caste and ethnicity. For long time, Nepali society has been seen as being structured into four diverse social or community groups: Bramhin, Kshetriya, Baisya and Sudra; with Bramhin placing at the top consisting of wealthy, intelligent and most privileged group of people, leaving the Sudra at the bottom comprising untouchable and most disadvantaged community people. In terms of ethnicity, as the Constitution recognizes, Nepali society has been clustered into two broad ethnic communities namely Arya and Mongol. Although there does not seem to be any significant social gaps as can be seen within the caste system, the division of society between Arya and Mongol has created much scarier gaps. Reforms aimed at narrowing such gaps — as with the problems of centralized government structure — did not bring any exciting outcomes.

The third, and the most relevant issue, is the developmental disparity caused not only due again to the centrally-driven public policies but also because of the geographic complexity. Geographically the country can be divided into three categories: Himal with approximately 17% of mountainous regions bordering China in the north; Pahad with about 68% high hills; and, Terai with remaining 18% of flatlands near the southern border to India. Although reform initiatives carried out during 1960s and 1970s showed some scale of sympathy by dividing these three broad geographic categories into five developmental regions (Eastern, Central, Western, Mid-Western and Far-Western), the developmental policies and programs implemented thereafter could not produce balanced outcomes. Consequently, newly labelled developmental regions remained severely imbalanced in aspects of life: politics, economics, social wellbeing (health, education etc.).

An assessment of modern-day local development policymaking

The landscape of modern-day local development policymaking in Nepal has been significantly changed, generally after the introduction of the Constitution in 2015 and precisely after the restoration of the elected leadership at the local level in 2016. These changes have been demanded by the new federal structure of the country. There are currently 753 new local governments, many of which were created by amalgamating previously created Village Development Committees (VDCs) and Municipalities under the LSGA (1999). These local governments are broadly categorised as rural municipalities (460) and urban municipalities (293) with further classification into municipalities (276), sub-metropolitan cities (11) and metropolitan cities (6). In addition to these local governments, there are 77 District Coordination Committees (DCCs) which are created to work as coordinating mechanisms between different levels of the government (federal, provincial and local) as well as among public and private sector agencies in a given territory.

What is more important is that the new federalist constitution specifies the functions to be solely carried out by local governments as well as jointly with federal government. Based on the Local Government Act (2017) as well as the relevant Articles on the Constitution, the following polity (structure), politics (process) and the policy (contents) can be illustrated as the local landscape of development policy in Nepal:

The polity

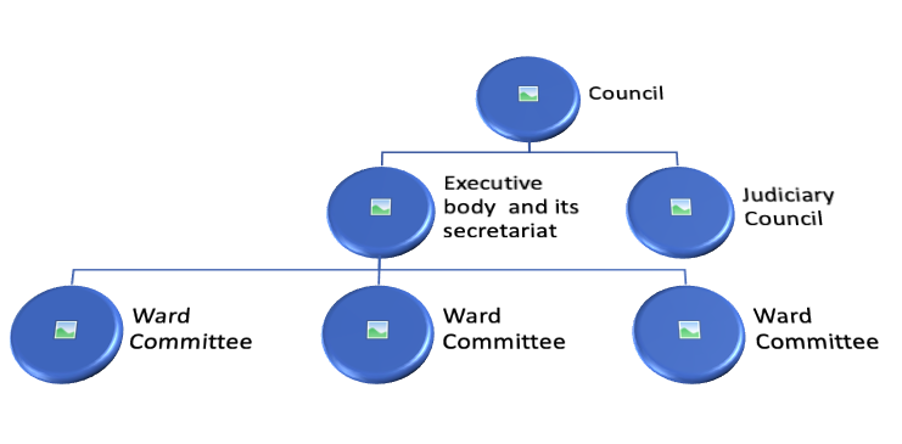

As a preliminary outlet of the local government, the federal government has prescribed the structure for all 753 local governments in Nepal. According to the constitutional as well as legislative provisions, however, local governments can redesign their organisational structure including their sub-municipal entities, number of employees and the inter-relationship between municipal and sub-municipal entities. While many local governments in Nepal are financially in a weaker position to challenge the federal or provincial government, it gives them a form of pressure to rely with what the federal government directs. The existing outlet of the policymaking regime seems like the following structure:

Figure 1: The existing generic organogram of local governments in Nepal

Figure 1: The existing generic organogram of local governments in Nepal

Although variations can be observed across municipalities, Figure 1 above gives us an idea of how the local governments in Nepal are structured for local development policymaking. According to the Local Government Act (2017), all the municipalities are required to organise the participatory planning process on an annual basis with clear budgetary ceilings, policy guidelines as well as programmatic requirements. A common process is that the executive body receives federal and provincial budgetary ceilings and policy guidelines which then needs to be reworked according to the municipal ability to raise revenues. The revised version of the budgetary and policy guidelines are then forwarded to the sub-municipal entities (ward committees) with clear mandate to deliberate them in communities. It has been observed that municipalities with more financial and technical capabilities have been organising informal forums at diverse communities to communicate such budgetary and policy guidelines as well as listen to what ordinary people in communities have to say. In others, ward committees organise broader semi-formal deliberative forums with the aim of discussing budgetary and policy guidelines with elites representing professionals such as teachers, health workers, NGOs, private sector and politicians. The end product of such deliberative forums — both at the semi-formal and informal levels — need to be forwarded to the executive body of the municipality. The executive board then forwards the proposals to the Council for final decision-making. All these tasks require at least nine different activities under three different stages.

The participatory planning process is not a new institution in the local government system in Nepal. Since the planning process has been brought forward to the Local Government Act (2017), it is legitimate to ask how much changes have been made to cope with or adjust to the new federalist structure of local government in Nepal. The foremost answer to this question can be ‘nothing’ because many steps in all the three stages of the participatory planning process remain the same as they were envisaged in the LSGA (1999). However, if we go a little bit deeper into it, municipalities are more autonomous in terms of how they would like to deliberate their development policies in communities. There does not seem to be any legislative obligations for municipalities to strict to; but instead, they are more powerful (than their predecessors) in designing the planning process according to their capacity and local circumstances. Only a few municipalities have shown such capacity to remodel the institution of planning, though their ideological ground, elements and processes, as well as the implication to local development policies, need to be carefully studied.

The politics

The procedural aspect of the new landscape of local development policymaking appears to be far more progressive than the previous model of local government in Nepal. As per the Local Government Act (2017), all municipalities must organise consultative workshops, if not deliberative forums, across a range of communities and neighbourhoods to help ordinary citizens explore, develop and prioritise their developmental needs. But they are not obliged to follow a specific set of institutions and processes. In other words, they are now free to set up their own institutions and processes to develop their local development policies and programs. However, in the last two years, not all the municipalities have followed this root to policymaking. As per the Auditor General’s annual reports, there are some municipalities which have taken decisions without organising such consultative workshops or deliberative forums. This raises a series of questions: (i) to what extent municipalities are obliged to follow procedures prescribed by a law promulgated by the federal government? (ii) whether laws framed by concerned municipalities can legalise their domestic policymaking regime? and (iii) what happens when municipalities do not go through consultative workshops or deliberative forums as part of their policymaking processes?

The answer to these questions is not simple, thus, we need a political approach. Because the Constitution puts local governments as the third tier in the federation, any legislative arrangements decided through local councils can be regarded as laws. And, the policymaking regime of local governments — if governed by the laws of respective municipalities — must be validated. No external authorities such as the Office of the Auditor General’s office can label the policymaking regimes of local governments as void. The newly designed local policymaking regime of local governments in Nepal, therefore, is a complex institution.

In terms of the process of local development policymaking, we should take citizen engagement as a criterion to assess whether the landscape of participatory policymaking has been changed over the years. For a variety of reasons, the local governments without electoral politics from 2002 to 2016 had geared the notion of citizen engagement as one of the mandatory steps towards policymaking. One reason was the provision of performance measurement, a grant allocation tool adopted by the Local Bodies’ Fiscal Commission (LBFC), which obliged all the local governments to ‘maintain citizen participation in the planning process.’ This exercise has been broken after the introduction of the Local Government Act (2017) leaving the potential for ‘citizen engagement’ in the fog. Interview materials gathered for this research suggest that ordinary citizens are relatively unhappy with the current system of local development policymaking partly due to the nature of the representative local democracy. Elected officials continue to claim that they represent ordinary citizens through ballot-papers hence they do think less practicality to go back to communities to ask for ordinary people’s developmental needs and, or policy preferences. Balancing the thirst of ordinary people to participate in the development policymaking and unwillingness of elected politicians to deliberate the local developmental policy in communities requires endogenously instigated institutional reforms across all the local governments in Nepal.

The policy

What should be the development policy of local governments in Nepal? This is a question the Constitution leaves upon to be answered by the local governments themselves. If we carefully look at Annex 8 of the Constitution, there is a list of policy areas which need to be addressed by local governments through the formulation of sector-specific policy. Similarly, Annex 9 of the constitution mandates all three tiers of the federation — federal, provincial and local — to jointly formulate policies. How it is possible to bring diverse government entities into a single platform of policymaking is relatively unclear, though there are some recent initiatives from the federal government such as the promulgation of the Intergovernmental Relations Act (2020).

Based on the experience of the last three years across a range of municipalities, two key determining factors were noted to be important in (re)shaping the contents of the local development policy. The first is the domestic revenue-raising capacity. Municipalities with stronger revenue-generating capacity are found to be designing policies with innovative contents while others with financially more reliable to the federal government appear to be following incrementalism, a development policy path that moves slowly with less innovative policies. The second is the administrative capability to introduce and handle innovativeness. There are only a few number of municipalities which seem to be regularly showing innovative local development policies hence attracting national media. The elected leadership can obviously be behind the scene but the bureaucratic readiness as well as the ability to handle such innovative policies is crucial in such situations.

It’s without question that Nepal’s local development policymaking regime is undergoing a transformation in order to adjust to the recently established federalist structure in Nepal. Many of the local-level institutions have been adapted from the Panchayati period (1960–1990), though significant changes in terms of the structures, power and resource-distribution mechanisms have been made. These structures require a rigorous evaluation, but what is clear is that there are real strenghths within them for how citizens can directly participate in the local policymaking.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Arrows. Credit: Geralt, Pixabay.

1 Comments