Esha Shah argues current theories on development and globalisation fail to take into account the powerful impact affective atmospheres have on shaping social and political reality. In seeking to address this, she uses popular Hindi films to sense the contemporary mood and to show how the shifts in the way poverty situations are depicted hint at changes in public morality.

Esha Shah argues current theories on development and globalisation fail to take into account the powerful impact affective atmospheres have on shaping social and political reality. In seeking to address this, she uses popular Hindi films to sense the contemporary mood and to show how the shifts in the way poverty situations are depicted hint at changes in public morality.

This article links to an earlier India At LSE post: Can film offer an(other) authoritative source of development knowledge? by David Lewis, Dennis Rodgers & Michael Woolcock

If the rich could hire others to die for them, we, the poor, would all make a nice living

This is a Jewish proverb that figures in the classic film Fiddler on the Roof. The subjective positions of the rich and the poor in this proverb are entangled in an ironical way. The rich are afraid of dying and the poor do not have enough for living. From the point of view of poor people, while the deaths cannot be exchanged for money, the rich would not hesitate to trade them if they could. Historian David Hardiman discusses another such ironical proverb linking poor peasants with Marwari-Jain money lenders: “A Baniya’s logic can never be understood; while he never drinks water without straining it carefully, he drinks blood freely.” In these representations of popular culture, poor people are not always portrayed as occupying the position of deprivation, need or marginality in relation to rich people.

Yet this is not how poor people and poverty are visualised in the policy discourses. Development discourses routinely conceptualise poverty in terms of different forms of lacking – for instance, lack of health, income, resources, well-being, education or capabilities. They also widely employ mechanical, spatial, and hydraulic metaphors such as up/down, below/above, centre/periphery, inside/outside, inclusion/exclusion to quantify or qualify the phenomena of poverty which is largely described in negative connotations.

In fact methodologically speaking, the development discourses and theories represent the “researching subject” (the researcher or policy maker) rather than the “researched subject” (the poor person) and have a kind of muting quality about the life situations of poor people. These discourses rarely consider poverty in relational terms, as inter-subjective experience, or as an affective (emotional) response.

In my essay Affective Histories: Imagining Poverty in Popular Indian Cinema I have mapped the way in which the “poverty situations” as inter-subjective affective dramas have been depicted in popular Hindi cinema since independence. How is poverty imagined in popular culture? How do poor people experience their situations? What are their aspirations, their personal journeys, their perceptions of the deprivation they suffer? How has this imagination changed in the course of half a century of the Bombay cinema? How have poverty situations been embedded in the psychic structures of public morality?

Popular cinema in India plays a highly influential role in shaping politics of public culture and public morality. It is not only considered the world’s largest film industry, but on an average day, it releases two and half feature films which are watched by 15 million people in 13,002 cinema halls. Tracing poverty as affect, I have divided popular cinema in Hindi in three distinct phases, which arguably also roughly reflect the distinct socio-economic and political eras in the history of independent India.

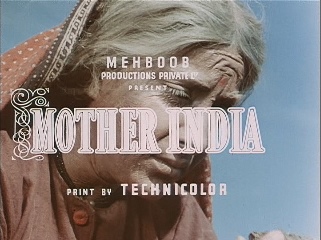

During the 1950s to late 1960s, the agrarian theme towards building a community – village and nation – dominated the cinematic representations. This is when the conflicts between rural and urban, and rich and poor were popularly depicted in Hindi cinema, in which the rural and the poor were morally privileged. The essay discusses the classic film Mother India in detail. In the iconic story of Radha the film epitomises the strength of India’s hard-working, courageous, and morally and ethically upright toiling masses. In doing so, the film depicts the utopia of Nehruvian dream of progress but not at the cost of dishonoring or disgracing what it transforms.

The mood of the representations of poverty in Hindi cinema shifted in the 1970s. This was a crucial period in Indian politics. The romantic ideas of progress of nation-building of the 1950s and 1960s had given way to multiple challenges to the authority of Indian state. Unemployment and inflation were on the rise and the Bombay film industry was acutely influenced by the wide-ranging political changes. It responded with what film historian Madhav Prasad calls “populist aesthetic of mobilisation”: a new phenomenon of films centred on the images of angry young man, anti-hero or proletariat hero.

As an example of this era I discuss the cult film Deewaar which portrays poverty as shame and humiliation as a precursor to anger and rage of the anti-hero. The character of adult Amitabh Bachchan is deeply and formatively affected by the humiliation that his mother experienced living on a pavement with two children and working as a menial laborer at a construction site.

My claim is that the fear of pauperisation, and especially the stigma attached to menial labour, is so deeply ingrained in the collective psyche and memory in Indian society that it is associated with shame and humiliation. Implied in this stigma is a long history of imagining the lives of the laboring classes – those who work with mud, stone, bricks, sand and earth – as worthless, lesser, and lower lives.

The anti-hero, however, eventually acquires the riches and purchases the entire building for which his mother had lifted bricks. I argue that the affective investment in the film in the images of humiliation and shame caused by destitution is a ploy, merely a reference point that contrasts with the fantasy space of glittering prosperity that unfolds.

The constitution of this fantasy became increasingly aggressive in the 1990s. A series of blockbuster films highly popular among the Anglo-American diaspora made in this period represented a new trend. The agrarian and rural themes disappeared from these post-liberalisation films and emerged two contradictory trends: one of them, termed as the “Bollywoodisation” of Indian popular cinema, depicted the grandiose urban life styles focused on the Anglo-American diaspora; the other portrayed the crime-ridden, rotting underbelly of urban India.

In these depictions, the fantasy of the glitter of urban modernity and its “dark” shadow have been resolutely separated in the distinct cinematic frames which denote the absence of any direct social and cultural intercourse between the rich and the poor. I argue in my essay that the shifts in the depictions of poverty thus denote a journey from discussions on “possible nations” to the emergence of “two nations” alienated from one another. The disastrous effects might even provide some explanation for numerous incidents of farmers’ suicides in the last decade and half.

Current theories on development and globalisation fail to take into account the powerful impact affective atmospheres have on shaping social and political reality. They also have not adequately explained the widespread dystopian utterances in rural India made in the background of, for example, a quarter million farmers committing suicides over a period of decade and half: “we are like the living dead”, “nothing can possibly change”, “how long should our lives be tied down to mud?” “our lives are wasted making dust and sifting mud”. My essay has used popular Hindi films to sense the contemporary culture and to show how the shifts in the way poverty situations are represented in the fantasy narratives of Bombay cinema hints at the historical change in public morality.

This blog is based on “Affective Histories: Imagining Poverty in Popular Indian Cinema”, Esha Shah’s chapter in D. Lewis, D. Rodgers, and M. Woolcock (eds.) Popular Representations of Development: Insights from novels, films, television and social media which was published by Routledge this year. Read the book review on LSE Review of Books.

About the Author

Dr. Esha Shah is a fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, India. She is currently working on what she calls affective histories of the modes of rationality and science – how affects and emotions lead the way for belonging ahead of the modes of rational, deliberative and epistemological thought.

Dr. Esha Shah is a fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, India. She is currently working on what she calls affective histories of the modes of rationality and science – how affects and emotions lead the way for belonging ahead of the modes of rational, deliberative and epistemological thought.

1 Comments