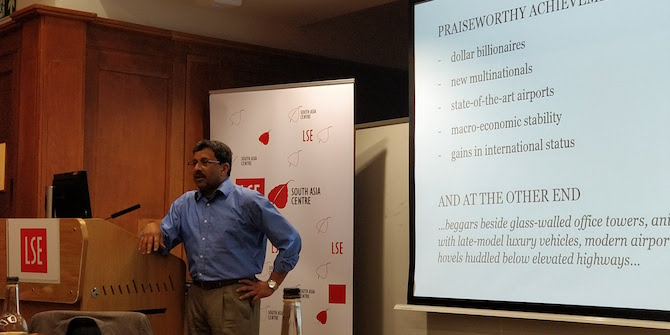

Earlier this month, Kaushik Basu, Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank and C. Marks Professor of International Studies and Professor of Economics at Cornell University, delivered a lecture at the London School of Economics and Political Science. The event was chaired by Craig Calhoun, and Amartya Sen and Lord Nicholas Stern were discussants. Ankita Mukhopadhyay reports.

Earlier this month, Kaushik Basu, Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank and C. Marks Professor of International Studies and Professor of Economics at Cornell University, delivered a lecture at the London School of Economics and Political Science. The event was chaired by Craig Calhoun, and Amartya Sen and Lord Nicholas Stern were discussants. Ankita Mukhopadhyay reports.

What happens when distinguished Economists like Amartya Sen, Kaushik Basu and Lord Nicholas Stern are discussants at the same event? LSE, on 3 March 2015 saw a packed Old Theatre Hall for one of the most illustrious events of the year. The expectations were high, and the lecture left the audience wanting for more.

Kaushik Basu, Chief Economist of the World Bank, spoke on ‘Law Economics and the Republic of Beliefs’. He argued that the way in which Law and Economics as a subject is currently taught in Economics is flawed. He supported his argument by with insights from his research and work in India and game theoretical models.

“What is the standard Law and Economics model?”

One of the things that most frustrates Basu is how corruption negatively affects the lives of so many and yet persists. He gave an example of the food rationing system in India, where there is currently a huge amount of leakage in the mechanism. Middlemen hike up prices and as a result the poor still cannot afford food, even though the law stipulates that they have the right to it.

There has been agitation in the streets against corruption, but Basu argued this agitation has to be combined with analysis. He gave an example from his time as Chief Economic Advisor in India when he wrote a paper on corruption and posted it on the Ministry of Finance website. According to the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, both taking and giving a bribe is considered a crime. As a result, when the bribe has taken place, both bribe giver and bribe receiver hide the fact that the bribe happened to avoid being penalised by the law. Basu called for this law to be changed, in particular when demands for bribes compromise fundamental rights, i.e. harassment bribes. In these cases, the receiver has to be punished more than the giver in order to change the behaviour of the person asking for bribes. Furore broke out in response to the paper, but although then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and others admitted they did not agree with the idea, Basu was never asked to remove the paper and it remains on the Ministry of Finance website today.

Basu stands by the paper and highlighted that one of the recurring issues, heard mainly in developing countries, is that many laws are seen as fine on paper but stall because they are not properly implemented. He sees this as the methodological problem between law and economics which handicaps progress.To give a better understanding of this complex relationship, Basu drew on Gary Beker’s economic model, which takes an amoral view of individuals to weigh up net returns against the probability of getting caught and punished for illegal activity. For example, if the government enacts a law stating that mining is an illegal occupation, then:

- Probability of getting caught = p

- Fine = f

- The venture is worthwhile if B > pF

- No crimes happen if B ≤ pF

In his model, Beker indicates that the government has control over the variables p and F, in that they can increase the probability of catching criminals by investing in policing, or they can increase the fines. Increasing p can be difficult and expensive, in that you need a large and efficient police force and machinery to catch those committing the crime so raising the fine might therefore be seen as the cheap and easy way to make pF greater than B and deterring the crime. However, the fine cannot be raised too high because (for example) those committing the crime are unlikely to be in the position to pay large sums.

Basu recognised Beker’s model as an important contribution to the discussion around the nexus between law and economics but he felt there was a fault line which centred on the question “why should a law change behaviour?” When a new law comes it is assumed the pay-off calculation, and therefore behaviour, changes. But why should it, when the law is ultimately just ink on paper? Basu argued that when economists write down the “economy as game”, as they so often do, they fail to write down the full game. In particular, the police, courts and magistrates are excluded and treated as robots which will automatically follow the law rather than autonomous entities, potentially responding to different incentive structures. If these groups continue to behave as they did before the law was introduced the pay-off calculations simply remain the same.

Is behaviour = pay-off?

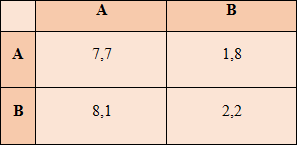

Basu used Prisoner’s dilemma to explain his theory. According to Prisoner’s dilemma, two players are given choices. He set the game up like this:

In this game the incentives are such that it is always worth both players selecting action B. If the other player selects A, they will get the maximum pay-out of 8, but even if both players select B they will get a pay-out of 2, higher than the one they would get if they selected A and the other player selected B.

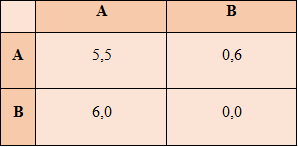

The current theory of Law and Economics will fine those choosing action B to make it less attractive:

There is the assumption that a new law has changed behaviour because it has created greater incentives for selecting A.

But when a new law is enacted and a fine is imposed, this assumes a third actor: the person who charges the fine. If there are three players (or more, if not just the police but also the courts and the judge are included), the two person prisoners dilemma ceases to effectively map incentives and penalties.

If pay-off functions are not changed, how can law affect behaviour at all?

Basu argued that behaviour change can still come about, if actors expect others to behave differently. A law can therefore deflect the negative action by creating an alternative “focal point” to push behaviour change. Basu illustrated this point with a second game where both players are asked to choose a common square in a set of ten without communicating. If all the squares are the same, one never knows what the other person will choose, but if a gold coin is placed in one square both people will most likely choose the square with the coin. According to Basu, the addition of the gold coin creates a focal point for action, and therefore a self-sustaining shift in behaviour. So the game of life can remain unchanged but an effective law will create a focal point which encourages one behaviour equilibrium, or social norm, over others. The role of different actors remains key – for example the mindset of those who do (or do not) enforce the law – but Basu suggested the focal point idea is a useful tool for establishing what makes a good or bad law.

Conclusion

Nick Stern questioned the usage of Beker’s model in the presentation and pointed out a fundamental problem which is the understanding of what constrains punishment. Retribution should always be limited by the nature of the offence. The model has a technical problem because it raises questions of appropriateness of punishment and Stern highlighted the equilibria can be changed by the fury of people, a good example being Xi Jinping campaign on corruption in China, launched in response to popular pressure so great that it threatened the existing power structures. In what circumstances can equilibrium be found?

Amartya Sen praised Basu’s lecture for effectively combining elements of the technical with those of the practical. He also raised the issue of what makes an individual move from one focal point to another? A lot of people might want to but can’t due to circumstances. When you have two possible outcomes, both of them are still equilibria. Yet we have seen in the past that tipping points are reached, some sooner than others for a variety of reasons.

Basu ended the lecture by stating that we need to understand that there is a need for a focal point in law and economics, and a re-inclusion of third party individuals in this larger game of life, where law and economics as a discipline needs a revision.

Listen to the full podcast of the lecture here.

Image credit: LSE/Nigel Stead

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Ankita Mukhopadhyay is currently studying for an MSc in History of International Relations at LSE. She completed her undergraduate degree in History (Hons.) from Lady Shri Ram College , New Delhi and tweets @muk_ankita.

Ankita Mukhopadhyay is currently studying for an MSc in History of International Relations at LSE. She completed her undergraduate degree in History (Hons.) from Lady Shri Ram College , New Delhi and tweets @muk_ankita.