The Supreme Court of India’s ruling that privacy is a fundamental right is a victory for privacy advocates. However, by questioning the foundations of India’s unique identity scheme it may prove a roadblock to fighting corruption and modernising the economy, writes Abhishek Parajuli.

On 24th August, India’s Supreme Court decided that India’s 1.3 billion citizens have a fundamental right to privacy. A victory for privacy advocates, this decision now threatens the Modi government’s most important policy initiatives and may inadvertently hurt India’s poor. It is thus a bittersweet victory; a step forward for privacy but a potential setback in the fight against corruption and the drive towards modernising the economy.

The reactions from some of India’s leading political figures reflected the importance of the ruling. The ex-finance minister P. Chidambaram called it one of the most monumental rulings since the advent of the constitution and the de facto leader of the opposition Rahul Gandhi tweeted: “Welcome the SC verdict upholding Right to Privacy as an intrinsic part of individual’s liberty, freedom and dignity. The SC decision marks a major blow to fascist forces.” Regardless of where you stand politically, understanding the implications of this decision is crucial as it will impact a number of core policies.

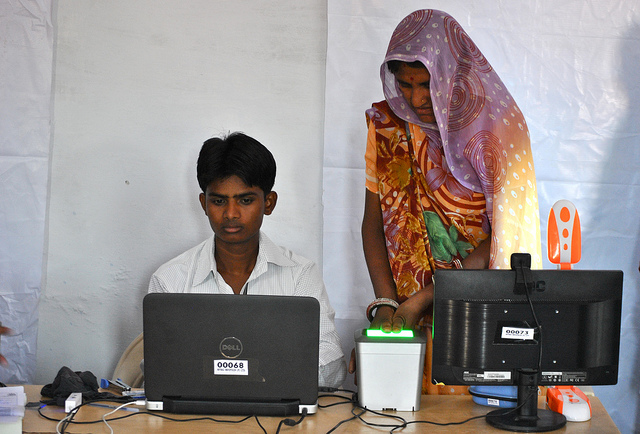

The case stemmed from the national biometric ID system, known as Aadhaar. The government has been trying to enroll all 1.3 billion Indians by capturing iris and fingerprint scans. Concerns that personal data were being centralised were fuelled when the government started using the ID system to transfer state benefits. It also used it as a foundation – incidentally the meaning of the word ‘Aadhaar’ in Hindi – for other innovations like a payment system that allows transactions using just fingerprints.

Aadhaar has faced legal challenges before but emerged largely unscathed. When the government made the card essential for filing income taxes, the Supreme Court deemed it constitutionally kosher with a few reservations. The Court did forbid the government from making Aadhaar mandatory, with a few exceptions, for welfare schemes but this decision has been flouted without censure.

Finally, there are also legal uncertainties about the way the policy was introduced in parliament. The Aadhaar Act 2016 was launched as a money bill. These are bills related to government taxation and expenditure and the Indian constitution gives the lower house – the Lok Sabha – exclusive jurisdiction with the upper house playing only an advisory role. Critics argue the government misclassified the bill to ram it through the upper house where it lacks a majority. While these challenges have chipped away at Aadhar, its core has remained intact.

Now, however, that foundation is at risk of collapse. While the court did not rule on the ID initiative itself, the strong judicial support for privacy will be a blow to the Modi government which had argued that privacy is not a fundamental right. Two of the government’s core policy initiatives will falter if the court now rules against Aadhaar on the back of this.

The first is providing bank accounts to India’s poor. Modi’s focus on this issue was driven by the fact that in 2011, only 35 per cent of Indians had access to a bank account which was much lower than the 50 per cent global average. Bank accounts allow the poor to save money safely and access credit without paying usurious rates to local moneylenders.

But India’s poor did not have even basic identity documents like birth certificates and so the banks were out of reach. The ID scheme helped overcome this bottleneck and the BJP-led government was able to get almost 220 million new bank accounts opened within one and a half years.

The second related goal is a war on corruption in state welfare transfers. Most of these transfers happen through food and fuel allocations and middlemen often siphon off large chunks of the aid. What is more, illiterate Indians are often unaware of their rights and so some of the benefits are rerouted into the private market and sold back to them.

Here too the Aadhaar ID is critical. It would allow direct cash transfers that could go straight from the treasury into a poor recipient’s bank account. The head of India’s National Planning Commission once said that only about 16 per cent of the funds for the poor reached recipients. That figure is probably out of date but it does show the scale of the problem. The direct cash transfer model has helped tackle this graft.

All this is not to say privacy advocates did not have reason to worry. Creating a centralised database of 1.3 billion Indians with biometric, demographic and potentially banking and consumption records sounds like a tantalising invite for a hack. While strong security measures may help, collecting the minimum necessary information and avoiding centralisation of databases serve both privacy and safety concerns.

Two breaches in nations with strong data protection norms illustrate this danger. Last month, Sweden had a serious breach exposing details of defense and witness protection programs. In fact, the leak almost brought down the government there. In 2015, a breach in the US Office of Personnel Management affected 21.5 million federal employees. The Indian government has pledged proper protections but it should keep in mind that hackers may still make it through.

The court’s decision is thus a bittersweet victory. A looming threat to privacy may have been averted. But, the Aadhaar ID system has tremendous potential to transform the lives of India’s poor and so it may come at a cost. Now that the court has settled the constitutional question on privacy, it will now turn to a case on the ID system itself. Its decision there will be monumental for India’s future.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Abhishek Parajuli is a Clarendon Scholar of Politics at Nuffield College, University of Oxford and a Peter Martin Fellow at the Financial Times. I can be reached at abhishek.parajuli@ft.com and abhishek.parajuli@nuffield.ox.ac.uk