With the announcement of the FATA reforms, the time for change in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) may have finally come. Samra Anwar and Abdur Rehman Cheema give a lowdown on why democratic processes have taken so long to arrive and the challenges ahead.

With the announcement of the FATA reforms, the time for change in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) may have finally come. Samra Anwar and Abdur Rehman Cheema give a lowdown on why democratic processes have taken so long to arrive and the challenges ahead.

With Pakistani Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi re-initiating the process of mainstreaming Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), the region is again in the limelight. Unlike his predecessors, Abbasi seems to be serious on the matter as he is now the chair of the FATA Reforms Implementation Committee, and is joined by the Chief Minister of Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KP), Chief of Army Staff and Commander of 11 corps as its new members.

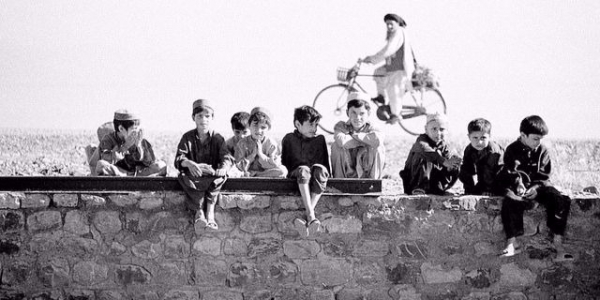

The people of FATA, Pakistanis as per the Constitution, have waited for a long time for better quality of life and a level playing field. For over two millennia, the region now included in Afghanistan and KP of Pakistan, while dominated by great powers, was frequently invaded. However, during this time the local tribal structure helped the local inhabitants in continuing with their independence.

Under the British rule, the tribal Jirga system was kept intact. Both criminal and civil cases were decided by the Jirga, and its decisions were unanimous. However, the British gave it legitimacy after some modification, while also introducing the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR).

Just before the creation of Pakistan in June 1947, Muhammad Ali Jinnah met Ghaffar Khan in Delhi to negotiate conditions for cooperation. Khan agreed to support Pakistan on the condition that tribal areas be merged with settled areas of North West Frontier Province (NWFP), the older name of the KP province. Subsequently, as per historical records, a new agreement was reached with tribal chiefs to maintain the existing arrangements in tribal areas in exchange for support to Pakistan. The agreement thus reached was revised by the government in 1952 to gain greater control over the tribal areas.

In 1970, the tribal areas of Dir, Swat, Chitral, Malakand and Hazara were included in NWFP while the rest of tribal areas were declared as Federally Administered Areas. Thus, two tribal areas were created in the North of Pakistan: FATA and Provincially Administered Tribal Areas (PATA) of NWFP. The administration of FATA was entrusted to Federal Government through the Governor of NWFP. Such constitutional position of FATA was created to guard the Durand Line as an international border and to focus on the highly under developed and poverty stricken areas of the country.

Administratively, FATA consists of two kinds of areas. It comprises of seven Political Agencies (Bajaur, Mohmand, Khyber, Orakzai, Kurram, North and South Waziristan) and six Frontier Regions (Peshawar, Kohat, Bannu, DI Khan, Tank and Lakki Marwat). These areas were controlled through political agents by the Pakistan Government until recently.

It was not until 1997 that the people of were given the right to vote. However, the election was on non-party basis, unlike in the rest of the country. The first general elections on a party basis in FATA were held in May 2013. This transition in the electoral process of FATA region was both an opportunity as well as a challenge. The process presented an opportunity to lead the development of democratic institutions in the area and helped in working toward ending FATA’s underdeveloped status.

However, there are some hindrances that could possibly keep the government from implementing FATA reforms. One of the major barriers is the strong opposition by some influential tribal influential people who believe that these reforms would be a threat to their historic norms and cultural practices. These local elites have the most to lose as they have enjoyed enormous powers and have been financially privileged by being legally identified with the draconian FCR. They have been ruling since the colonial period, and accrued more power when they were nominated by the state of Pakistan as custodians later on. This has resulted in corruption and underdevelopment of the area.

The inhabitants of this area are still deprived of a number of rights guaranteed by the Constitution of Pakistan because the area is still under FCR. For instance, Pakistan’s apex court is barred from exercising authority over FATA, and political parties were not allowed to operate in the area. Such rules and the aftermath of loss of internal control, gave prominence to the appointment of political agents and local tribal elders. Such elites have always been patronised by some political parties, who stand to gain seats in the National Assembly.

This model of governance has consequently resulted in hatred and rejection of the Pakistani government for acting as British had done in the past. While the political elite have enjoyed sovereignty over the area and live a life of luxury and exploitation, the general FATA population have lived in extreme poverty deprived of civic amenities.

According to a report released by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) as of 2016, two-third of people in FATA (73%), live in multidimensional poverty. A survey carried out by the FATA Secretariat in collaboration with the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics revealed that overall literacy rate in FATA is 33.3%, which is far less than the national average of 58% (2013-14). Similarly, the adult literacy rate in the region is 28% against the national average of 75%. The survey FATA Development Indicators Household Survey 2013-14, shows that the tribal region has consistently been one of the poorest regions in Pakistan.

An additional crucial factor that has held FATA back has been the existence of extremism and the Taliban, which have caused havoc to the region and have made the region more under developed and marginalised.

With the start of Afghan war, FATA became a homeland for militants due to the shared border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. However, many of these Jihadi groups turned against Pakistan once General Musharraf sided with the United States in the latter’s hunt for Osama Bin Laden. Pakistani military had undertaken several military operations to clear the Pakistani soil from those involved in anti-state activities.

The proposed reforms

The committee on FATA reforms proposes a seven-point agenda and abolishment of Article 247 of the Constitution of Pakistan. It suggests that either FATA be merged with KP, or creation of a separate FATA Province, or giving FATA the status of Executive Legislative Council (like that of the Gilgit Baltistan).

According to the report, in order to achieve peace and prosperity in the region, the most appropriate step would be to merge FATA with KP province. The committee suggests that reforms should take an integrated approach to bring all the stakeholders on the same page, and should also focus on strengthening institutions with gradual approach to influencing norms and culture of tribal Pashtun. Local politicians must be on board to negotiate some of critical issues such as girls’ education and participation of women in the electoral process. Unfortunately, the female literacy rate in FATA is an alarming 7.8%.

The central role of free and fair elections in the democratic process and political stability is clear and evident as elections are a cornerstone of democratic consolidation in any country. Through conscious advocacy of democracy as a means to development of the area, an implicit demand for a meaningful electoral reforms agenda arises. The main focus remains on material progress and development of the area.

Although military operations in the region have worked toward eliminating terrorism, the aftermath of such operations has left thousands of people homeless and displaced.

Without mainstreaming FATA, no amount of military operations and sacrifices of the nation can ensure peace unless backed up with the creation of new economic opportunities for the people living in those regions.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About The Authors

Samra Anwar is a development consultant with interest in issues of public policy and governance based in Islamabad, Pakistan. E-mail: samraanwar@gmail.com

Samra Anwar is a development consultant with interest in issues of public policy and governance based in Islamabad, Pakistan. E-mail: samraanwar@gmail.com

Dr. Abdur Rehman Cheema is Charles Wallace Fellow at the Sustainable Places Research Institute at Cardiff University. E-mail: arehmancheema@gmail.com

Dr. Abdur Rehman Cheema is Charles Wallace Fellow at the Sustainable Places Research Institute at Cardiff University. E-mail: arehmancheema@gmail.com