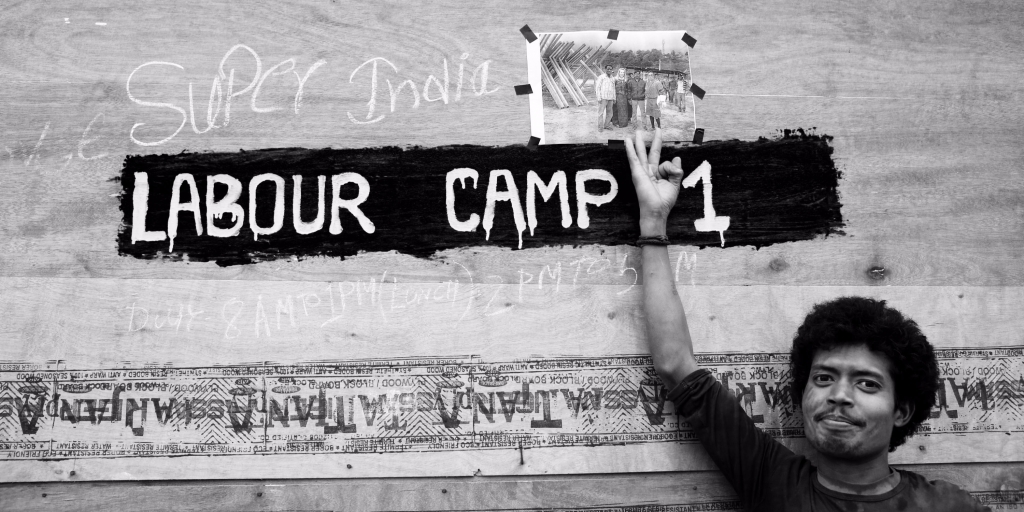

Indian labourers, along with the aid from India, are integral to Bhutanese economy. In this photo essay, Jaquelyn Poussot explores the problems they face — from local to geo-political level.

Indian labourers are everywhere in Bhutan. On roadsides, in tents, cutting boulders down to gravel sized pebbles, or moving large objects using make-shift devices. But what is their impact on Bhutanese society? Why are there so many of them and how are their facilities are permitted to be quite so tragic?

On visiting the housing of the construction workers I found that they were staying in an uninsulated, simple wood cabin with no windows. There were two wooden platforms which were made into beds, and one long bench fashioned from leftover building material. All of the tools in the make-shift kitchen are daintily hung along the wall. There was a beautiful 1990’s style sound system, with a subwoofer and two large side speakers, presumably for surround sound, although they were clumped all together on one table. It had a CD player which was playing beautiful Bollywood tunes.

Government data show there are nearly 45,000 legal Indian labourers in Bhutan, which is 6 per cent of the overall population of Bhutan’s 770,000 and 18 per cent of the working population.

In September 2015, increase in national wages, prompted by the Ministry of Roads (MoR) loosing able-bodied workers to better-paying hydropower projects, were only applicable only to Bhutanese labourers. Wages for unskilled laborers increased from 165NU/day to 215NU/day, roughly $3.25/day; providing, even the most low-wage earners, with a salary 70 per cent above the United Nations’ development poverty line of $1.90/day. Workers at sites above 8,000 ft were issued additional compensation of 600NU.

However, Indian laborers’ wages are negotiated separately on a contract basis without the protection of the Royal Government of Bhutan’s policies. With the increase wage adjustment came a new problem; the hydropower projects stopped hiring Bhutanese, on account that Indian workers were more affordable; directly contributing to the unemployment of Bhutanese. Current contracts and wage rates for Indian laborer could not be found. A report from a Bhutanese ex-road worker states that rages were comparable among the two work groups, but exact numbers were not accessible for comparison.

Stigma and health

According to the Health and Services Center in Thimphu, the first ever case of AIDS was reported in Bhutan in 1993. Many Bhutanese believe that the spread of HIV came to Bhutan by the Indian labourers. However, the RGoB requires all foreign labourers be tested for non-communicable diseases prior to employment, including, but not limited to HIV/AIDS. Although this type of testing is not required by the International Laborers Organization (ILO), Bhutan is legally permitted to make such requirements within their own jurisdiction. Complications come from the ethical conduct of such testing procedures. After a laborer qualifies for a job based on skill and merit, they are required to be tested. If a test comes back positive, that person may be fired and immediately deported. Often, they aren’t notified of the reason for for being fired. The situations under which workers are notified of their results can take place in non-private settings under which no emotional or medical counseling is provided. ILO reports that in many of these cases, the fired person frequently “disappear” and is never seen again.

In other circumstances, an employer might require “optional” testing prior to applying for the job. Since job placements are so coveted it is not uncommon for applicants to give “consent” just for the mere opportunity to compete for the job. However, this kind of consent is not considered “full” by the standards of the ILO as it is a direct violation of Human Rights laws of Body Integrity & Dignity.

In a third scenario, employers may draw blood for other kinds of testing and then secretly test for HIV without notifying the applicant. Those who test positive for HIV are in turn denied the position and may or may not be notified at all of their health status. A 2009 ILO report outwardly discouraged such testing on the grounds that it “represents a serious human rights violation” and is not an “effective public health response.”

As time went by, it seemed that I was the only one with the curiosity of how the Indians were treated and their well-being. Bhutanese people often avoid engaging with Indian labourers. When asked about this, there is always a bit of a hush tone to the quality of the response. A simple head gesture seems to echo the words of a local politician: “We have a saying here in Bhutan: ‘We like the Chinese, but we do not like China. And we like India, but we do not like the Indians.‘ “ Although workers may not arrive with such diseases as HIV, societal isolation in conjunction with absence of family, leaves many foreign laborers lonely. Thus, resulting in the higher probability of the use of sexual facilities, like dryangs, and increasing the likelihood that they do contribute to the spread of sexually transmitted disease and perpetuate the social stigma which renders them isolated in the first place.

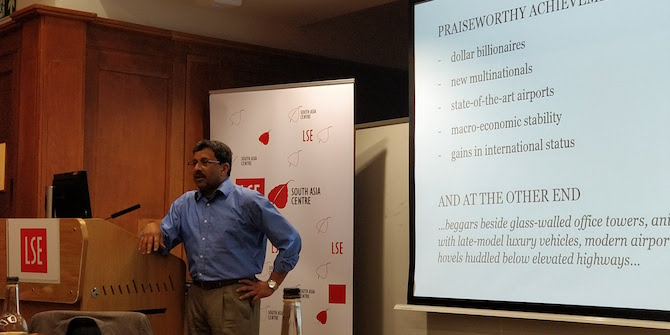

From micro to macro

At the geo-political level, the Government of India (GoI) is a huge supporter of Bhutan. The Counsel on Foreign Relations reported that India’s aid budget in 2016 was to contribute more than one billion dollars to Bhutan. This was 62 percent of India’s total global aid budget (2015). While Bhutan needs this aid, there is also no doubt that this money is well spent for India, as Bhutan is a gentle neighbor and well-sized buffer from China.

As of 2016, Bhutan’s hydropower funding is directly from the GoI, which is footing the bill for several projects whose budgets exceed $550 billion each. Financing is divided 30 per cent/70 per cent grant and loan, respectively. In addition to the hydropower projects, GoI is also directly involved in the funding of the major East/West road project which is at the root of Bhutan’s 11th Five Year Plan (2013-2018) for sustainable development. This road is promised to secure the Bhutanese people with a paved path for commerce and other public goods and services.

Image credit: Jaquelyn Poussot

These projects aren’t just funded by India, they are being manually produced by India’s work force as well. Indian companies, such as Jaypee, BHEL, T&D India and PES, compete in the bidding for such projects when presented by the Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB). These contractors independently contract their laborers, most of whom are hired from India. Lack of Bhutanese applicants isn’t just a result of limited technical training in the nation and an unskilled applicant pool, this generation of Bhutanese college graduates are most focused on securing a “government job” and blue collar jobs are looked down upon.

Economically, this business cycle with India needs to be closely examined. As India contributes aid and hydropower funding contributions, and Indian laborers are contracted to build the same, a substantial portion of workers salary is returning back into the economy from which it was gifted. That means, very little of the money that has been aided to Bhutan is actually remaining within the Bhutanese market. This decreases the opportunity to generate wealth, develop opportunity for local reinvestment or grow GDP and the result could be an un-payable debit and long-term, if not permanent, co-dependency on India.

These issues of Indian labourers in Bhutan are present from the mundane to the political level. They are faced with social stigma and neglect, along with poor living conditions but they seem to be happy. This is the paradox of the invisible class who are, literally, moulding the very landscape of possibility for this country.

This is an edited version of the article, Indian Labourers in Bhutan, published here on Jacquelyn Poussot’s blog in 2016. This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About The Author

Indian laborers are paid more than national minimum wage. They will not work on Bhutan national minimum wage. Those who work in hydro power projects are directly employed by Indian companies like JayPee and Hindustan CONSTRUCTION LTD., so, they are well paid by regional standards.