While Nepal’s elections were widely hailed as a major success, it would be a mistake to ignore many underlying issues that question the integrity and effectiveness of the recent elections, writes Nimesh Dhungana.

While Nepal’s elections were widely hailed as a major success, it would be a mistake to ignore many underlying issues that question the integrity and effectiveness of the recent elections, writes Nimesh Dhungana.

2017 may well go down in Nepal’s history as a year of elections. In the summer of 2017, Nepali voters participated in the local elections to choose over 35,000 local representatives across 77 districts of the country, overcoming a democratic vacuum caused by the absence of local elections for nearly two decades. In November and December of 2017, provincial and parliamentary elections were held, which resulted in the election of 275 representatives to the national parliament, and 550 representatives to the provincial assemblies.

For a country striving to institutionalise a newly adopted federal democratic model of governance, Nepal’s elections of different levels of government within a short span of one year is no ordinary achievement. Several other indicators also reinforce the success story of these elections. They were held for the first time after the promulgation of the new constitution in 2015, which guaranteed freedom of assembly and expression. Barring few exceptions, most political parties, including some agitating political groups from the southern plains of Nepal, took part in the elections. Voters’ participation was impressive, with the recent parliamentary and provincial elections registering an average voters’ turnout of 65%. Despite some sporadic violence before and during the elections, citizens cast their votes peacefully and freely throughout the country. The Election Commission (EC), a constitutionally mandated body, made efforts to ensure the elections comply with the basic standards of electoral practice. National and international monitors to elections, including the Carter Center, the European Union and the United Nations, were quick to laud the conduct of elections as a historic achievement in consolidating Nepal’s post-conflict democratic journey.

Holding periodic, fair and transparent elections is widely seen as an intrinsically desirable goal within multiparty and representative democracy. Under the logic of democratic accountability, elections are considered a primary vehicle by which citizens select promising politicians and penalise underperforming, or corrupt politicians. Despite this claim, notable scholars of democracy, namely Pippa Norris (2015), Adam Przeworski et al.(1999), Andreas Schedler (2002), Amartya Sen (2011), among others, have long raised caution against the unyielding faith in elections as a measure of democratic achievement. Elections often suffer from a lack of adequate and transparent information about the political leaders, raising questions over citizens’ ability to hold the leaders to account. Voters are subjected to undue pressures and manipulation by the political parties and their leaders. Local social dynamics, politics of identity, clientelism and favouritism, negatively impact voters’ ability to make a free and fair choice. As Sanders (2002) notes,

“voters must be insulated from undue outside pressures if they are to choose freely. If power and money determine electoral choices, constitutional guarantees of democratic freedom and equality turn into dead letters” (p.44).

These claims demand closer insights into the conditions under which citizens exercise their electoral right.

While Nepal’s elections were widely hailed as a major success, it would be a mistake to ignore many underlying issues that question the integrity and effectiveness of the recent elections. From my close reading of the mainstream and social media accounts, together with in-person interactions with ordinary voters during my short visit to Nepal in the eve of second phase of parliamentary and provincial elections, below I raise a few points that seek to challenge the ‘success tale’ surrounding Nepal’s recent elections.

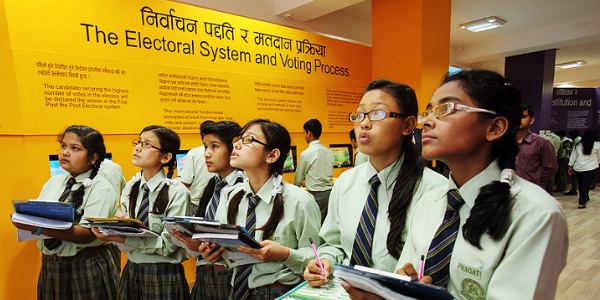

Schoolgirls experiencing the interactive learning process at the Electoral Educational and Information Centre in Kathmandu. Image source: Jim Holmes, USAID, Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

The menacing influence of money

That elections these days demand massive monetary resources is hardly surprising. With the recent elections, Nepal seems to have also joined the long list of democracies where money has become a normal and even legitimate instrument for electoral competition and subsequent success. Consider this example. The EC, as a legitimate body to regulate electoral proceedings, set a maximum ceiling of per candidate expenditure for running for the first-past-the-post election to Nepali Rupees (NPR) 2.5 million (equivalent to about USD 25,000). For a low income country with a per capita income of USD 730, this move by the EC should itself serve as a warning sign about the growing influence of money in elections. This poses a huge barrier for monetarily disadvantaged yet capable politicians to contest elections, a concern that was raised by a few politicians. Without first amassing enough monetary resources, it is seemingly becoming impossible for politicians to secure a candidature from the political parties, let alone contest and win elections. Increased influence of money also raises the risk of wealthy individuals and businesspersons pulling the strings of elections, by either securing candidatures themselves, or by promoting candidates of their choice. Not to mention more money means more likelihood of election-related malpractices, as reported by the media in the eve of recent elections. Despite a code of conduct issued by the EC against using money or other resources to manipulate voters, violations of code of conduct was reportedly rampant, exposing a lax state of regulatory authority in holding the political parties and leaders to account.

Elections without engagement

Underlying the democratic accountability logic of elections is that citizens have the time and opportunity to engage with, and evaluate the political leaders and parties contesting the elections. This demands sufficient time for interaction and deliberation between candidates and voters. Amidst the priority and pressure to hold elections, Nepali voters saw the opportunity for engagement between voters and candidates compromised. Most of the political parties made public their election manifesto in haste. Efforts to bring parties’ manifestos for public discussion were seriously limited. From the time of formally filling in their candidatures, the candidates had barely over a month time to make themselves and their party’s agenda available for public scrutiny. This resulted in rushed election campaigns that, on the one hand, put undue competitive pressures upon candidates. On the other hand, it meant little opportunity for the voters to demand answers from the political parties and candidates about the nature of political representation being expected across different political positions. This was particularly problematic as the elections marked the formal entry of Nepal into the federal system of governance. The representatives to the state assemblies were being selected for the first time in Nepal’s history, demanding sufficient opportunity for citizens to weigh in their choices. The relative hastiness by which the elections were organised thus raises question that citizens had enough opportunity to make an informed assessment and selection of their representatives.

The rise of misinformation machinery

The use of social and electronic media outlets in Nepal’s recent election campaign was unprecedented. This in itself is not a worrisome sign. The problem is the materials circulated through such outlets, many of them seemed intent on spreading (mis)-information, rumours, and so-called “fake news” against politicians and candidates. Such materials forced candidates into an intense and somewhat unwarranted battle of rebutting what they claimed as politically motivated rumour. In another instance, a candidate sought legal recourse over the election defeat, which he blamed to a fake news circulated during the silence period. Political leaders and parties, in turn, skilfully deployed social media platforms as a blunt instrument to circulate populist rhetoric and discredit oppositional leaders. Whether or to what extent these practices impinged upon the free will of ordinary voters, or what implications they may have for the long-term health of Nepal’s democracy, remains an open question. But the fact that there was limited space for face-to-face interaction between voters and candidates, combined with a serious lack of means to verify the authenticity of online materials, it is reasonable to assume that citizens’ ability to make an informed choice was compromised.

Conclusion

There is no denying that recently held Nepali elections marks a major achievement in institutionalising the country’s hard-earned democratic and constitutional victories. However, to bask on the success of elections, measured in terms of number of positions filled, turn out of voters, peaceful organisation of elections, and to discount the underlying flaws of the elections would be a grave disservice to Nepal’s democracy. The task is to move away from the measures that mimic prevalent definition of electoral success and focus on conditions that enable citizens to make a free and fair selection of their representatives. The observations made above are merely indicative, not exhaustive, list of conditions that deserve careful attention to strengthen the integrity and usefulness of elections. The obvious step is for the Election Commission, as an apex regulatory body, to revisit its existing mandate and mission. Based on which, fresh and enforceable codes of conduct could be developed for future elections. Equally important is for the media, independent monitors and civil society actors to reconsider their scope and strategy of monitoring the elections. A closer involvement of social scientists in building our understanding of the messy realities under which citizens exercise their electoral rights seems urgent. Without such collective efforts on the part of Nepali state and societal actors, elections’ basic goal of democratic accountability seems ever elusive.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Nimesh Dhungana is a PhD candidate at the Department of Methodology, LSE. His PhD research explores the notion and practice of social accountability in the context of Nepal’s earthquake recovery. His interests also span multiple areas of research within politics of development and disaster, governance, rights-based development, community mobilisation and South Asian politics. He Tweets @Nimesh724.

Nimesh Dhungana is a PhD candidate at the Department of Methodology, LSE. His PhD research explores the notion and practice of social accountability in the context of Nepal’s earthquake recovery. His interests also span multiple areas of research within politics of development and disaster, governance, rights-based development, community mobilisation and South Asian politics. He Tweets @Nimesh724.

In pursuit of the trees, the author has missed the forest. The basic flaw with Nepal’s elections has to do with “political match fixing” used to defeat the opponents. Unlike in the past elections when a candidate file his/her nominations from more than one constituencies, to ensure his/her victory. This time such practices have been banned and in its place we have now so called political alliances that has reduced electoral game neither fair nor free.