The under-representation of expert women in the media is a global trend with women more likely to be invited onto television debates to discuss gender and sexual violence than science and technology. However, lessons can be learned from the UK according to Reshma Patil.

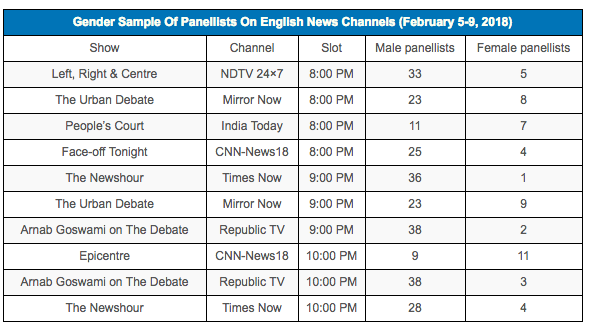

For five days starting February 5, 2018, IndiaSpend counted the number of men and women who appeared as panellists (commentators/spokespersons/newsmakers) on debates on 10 English news channels, between 8 pm and 10 pm.

Over four times more men than women–a total of 264 men as opposed to 54 women–appeared as panellists during the sample period, indicating the under-representation of women’s views in the broadcast media.

The gender count was restricted to invitees (not anchors) and debates (not interviews). The numbers were based on screenshots of groups of panellists who appeared in the first half of the shows (There may be minor discrepancies in total figures, as some panellists are brought in after the debate begins). The number of panellists on these shows ranges from three to 10 and some panellists appear on multiple channels the same evening.

The results highlight the need for further studies and empirical data to better understand why India’s professional women are largely unseen and unheard on primetime TV news in a nation with 780 million television viewers, more than the population of Europe. There are roughly 220 million viewers of English content and over 400 news channels in India.

Female panellists outnumbered their male counterparts on only one of the 10 shows in the five-day sample–Epicentre on CNN-News18 (which shifted from 7 pm to 10 pm from February 6, 2018).

Table showing gender sample of panellists on English news channel. Source: India Spend.

Women depicted less as experts, more as victims in news shows

The under-representation of expert women in the media is a global trend. In 2015, women comprised only 24% of the people “heard, read about or seen in newspaper, television and radio news, the same level found in 2010”, according to the five-yearly Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP).

A Mumbai-based media survey released last year showed that only two respondents–the BBC and IBN Lokmat, a Marathi-language news channel–agreed that “at least” one female voice makes for a “right mix” of television panellists. More than half the respondents in the study led by Population First and KC College were of the opinion that gender is not a decisive factor in the selection of panellists. But 15.78% of the respondents said that the “appearance” of panellists played a role.

In 2015, an International Federation of Journalists survey on media and gender in India showed that only 6.34% of respondents felt that women were depicted as experts/leaders in news programmes; 21.73% said they were depicted as victims.

Why is it important to ensure that more women professionals are seen on TV news shows? The depiction of gender stereotypes in the media could influence how communities perceive women and their place in society, say experts. “The media as a whole plays an important role in perpetuating or challenging cultural and societal norms so it is important that this industry is more representative of today’s society,” the British government stated in 2015, responding to a House of Lords inquiry into women in news and current affairs broadcasting

Why news managers tend to pick male experts for their mostly male audience

Men comprise half the viewership of Indian television and they watch news either at the start of or at the end of the day, India’s Broadcast Audience Research Council (BARC) estimated.

“Male TV anchors form a boys’ club with male commentators and (they) naturally gravitate towards them on most issues,’’ journalist Sagarika Ghose told the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) in Oxford, the UK, in an interview for a three-month fellowship paper on which this report is based.

There’s a belief among TV news managers in India that news audiences are “mostly male who prefer to get opinions from men rather than from women”, she added. There is also “discrimination against younger men, as TV and media platforms prefer elderly established male commentators”, she said.

Women called in mostly to discuss gender issues

Women speakers are generally called upon to speak more on gender than politics, geopolitics, defence, finance or the economy.

For example, all-male commentators discussed India’s Pakistan policy problems on three of the 10 shows sampled on February 5, 2018–Left, Right & Centre (NDTV 24×7), Face-off(CNN-News18) and The Debate (Republic TV).

An all-female panel appeared only twice during the sample period. On February 9, 2018, four women commentators appeared on Epicentre (CNN-News18) and on February 8, 2018, on People’s Court (India Today) to discuss gender politics around Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent remarks on Congress MP Renuka Chowdhury’s laughter in Parliament.

On The Urban Debate on Mirror Now, for example, there were no female panellists for a debate on the long-term capital gains tax, but an equal representation of three men and three women the next day discussed the goods and service tax (GST) on sanitary napkins.

In 2016, the websites SheThePeople and Safecity released results of a survey of over 100 conferences, events and television shows that revealed that women are mostly approached for comments on women’s issues. They recorded a quarter or less women panellists on news channels: 26% on CNN-News18, 25% on NDTV 24×7, 18% on Times Now and 12% on others.

The highest number of women panellists were invited to discuss sexual violence: 39%, followed by 26% on panels on crime and social issues. Women’s views were least heard on technology (14%) and industry (12%).

We look for best experts, gender balance isn’t priority, say anchors

Television anchors who were interviewed said they look for the ‘best’ speakers, irrespective of gender, and added that it is difficult to get women experts on business, finance and economic issues.

“I look for expertise, different points of view, also people who are articulate and comfortable on TV, which not everyone is,’’ said executive editor Nidhi Razdan, anchor of Left, Right & Centre on NDTV 24×7, in an interview for the RISJ paper. Women anchor five of the channel’s six prime-time shows.

“To be honest, I’ve never thought of panels from a gender perspective,’’ Razdan said, adding that she has hosted all-women panels too and frequently invites women to speak on politics and foreign policy. “Since I joined 18 years ago, it is women who have run NDTV, who hold top positions and anchor prime time shows. So, I’ve grown up in an environment that hasn’t really differentiated between men and women and we have been very lucky that way. So perhaps that’s why I’m also not as conscious of it. I look at inviting panels based on who I believe is the best person to speak on an issue, not their gender.”

Karan Thapar, former host of To The Point on India Today TV, said that the disparity in the number of men and women on news debates is “not deliberate… for example, some of the best and most knowledgeable speakers on foreign affairs are women”.

“I have to tell you, my priority is not to create balance,’’ Thapar said. “Gender representation is important but not the priority. Getting good people who speak well and are articulate is important.”

Political editor Marya Shakil at CNN-News18, one of the channel’s two primetime female news anchors, linked the shortage of women commentators to the shortage of women in charge of newsrooms. “Newsrooms are very, very male-centric,’’ said Shakil, “so they may overlook the contributions of women.”

Women not aggressive, assertive enough for TV debates?

Nearly every political party in India has female spokespersons but they are still a minority of one or two on panels. During the sample period, a 22 of 50 shows had all-male commentators, on issues ranging from Pakistan to Modi’s speech in Parliament, and the Ayodhya dispute to the Maldives crisis.

Journalist Kalpana Sharma noted that only “a very small number” of women are invited to political discussions. “It’s easier to get the ‘usual suspects’, almost always male, to come on panels rather than make effort at balance and diversity,’’ Sharma said. “Even if they get a token woman, they want her to be a film star, or a prominent socialite rather than someone with scholarship who will address the subject seriously. They need individuals who can perform, take up extreme positions, be rude, interrupt others, and basically be deaf to what anyone else is saying. Even men with sensible views are excluded because they will not perform. Of course, there are women who do; and predictably, they are the only ones called repeatedly.”

CNN-News18’s Shakil said she deliberately seeks women panellists, especially as spokespersons of political parties, and tries to give female panellists the last word on news debates, because “men tend to dominate the conversations” while women are “less assertive and aggressive”.

Reporter Karishma Vaswani does a piece to camera at the launch of the Indian Election train. Photo credit: Ben Sutherland, CC BY 2.0.

A lesson for India: How UK narrowed the gender gap in media panels

The broadcast news industry in the UK has experimented with several ways to end the under-representation of women’s views on television and radio.

The overall gender gap between male and female experts on flagship shows in news and current affairs broadcasting in the UK has narrowed from 4:1 in 2014 to 2.9:1 in 2016, research at the journalism department of City University, London, since 2013, indicates.

This 30% improvement is attributed to a slew of initiatives including the publicity around City University’s data on the under-representation of women experts in news programmes and its surveys on the attitudes of the media and professional women that may hinder their participation on television. The data stirred the House of Lords into asking for an investigation into the issue and in 2015, this report on the representation of female experts was released.

In 2013, the BBC Academy in London launched its first training day for expert women interested in becoming media commentators. There were 24 seats. Two thousand women applied.

In 2013 alone, at the end of four training days in London, Salford, Glasgow and Cardiff, the BBC Academy trained 164 women. The BBC continues to expand its Expert Women Database.

At the City University, Lis Howell, the director of broadcasting, leads a team of student researchers who regularly monitor flagship shows to record the gender balance of panels. Howell was of the opinion that journalism institutes in India could conduct similar projects to compel the media to explore ways to narrow the gender gap. The challenge would be finding the funds to pay student monitors to collect daily data. Television journalists would also question the methodology, Howell predicted, and “always be defensive”. Some broadcast journalists, for instance, responded to her department’s research surveys to say that it was more time-consuming to convince expert women to appear on screen, compared to men.

In 2013, when the City University published data on the lack of women experts in the media, the BBC considered it “a big strategic issue”, said Gurdip Bhangoo, head of Future Skills and Events at the BBC Academy, in London. In 2017, they had identified 48 new women experts.

“We aim to find 100 new expert women to appear in factual news programmes every year,’’ said Bhangoo. “Anecdotally, we found that more than half of the women we trained have been heard. We’ve got a format that works.’’ Bhangoo said that their initiative is replicable anywhere, but its success would depend on the “top editorial leadership” driving it. Imagine the potential for such an initiative in a nation the size of India.

This article has been edited for length and originally appeared in IndiaSpend where it can be viewed in its entirety.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Reshma Patil is a journalist and author whose stories have appeared in including Hindustan Times, Scroll and IndiaSpend. Previous roles have included associate editor of Hindustan Times and special correspondent of The Indian Express. She is a Fellow of the Chevening South Asia Journalism Program and holds a post-graduate diploma from the Asian College of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts with distinction (Political Science) from the University of Pune in India.