In Pakistan, parents disproportionately prefer having male children. Rashid Javed (Pau Business School, France) and Mazhar Mughal (Pau Business School, France) argue that this preference to have a son has a direct effect on the status of women at home, however does not increase women’s involvement in familial financial matters.

On 22 October 2019, Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security released the latest Women, Peace and Security Index. The index ranks 167 countries on indicators of women’s empowerment and gender equality. In the rankings, Pakistan fared poorly, placed 164th, followed only by war-torn Syria, Afghanistan and Yemen. The situation is hardly any better according to the Gender Inequality Index, Gender Gap Index and Social Institutions and Gender Index.

Women empowerment is a prerequisite for attaining political, social, economic, cultural, and environmental security among all peoples (UN World Conference on Women). Female empowerment is a broad term which encompasses the processes through which women gain greater control over the circumstances of their lives. It focuses on women’s control over physical, financial, human and intellectual resources as well as their agency (i.e. the capability and freedom to make individual life-choices). These dimensions of empowerment can be measured by indicators such as women’s employment in the formal sector, educational attainment and participation in household decision-making.

In a recent study, we examined how the practice of a parent preferring to have a son is intimately associated with women’s decision-making power at home. The phenomenon of son preference is still widely practiced in the Pakistani society. In patriarchal societies, parents prefer having sons over daughters due to economic, social and cultural reasons. Sons are regarded as economic assets and old age insurance as the son stays with the household and significantly contributes to the household economy, continues the family legacy and provides the parents old age support and care. Daughters, in contrast, are considered an economic burden. Parents must save for their dowry and daughters leave home to join their husbands – their financial and human capital thus becomes property of their marital household. A tragic consequence of this preference for boys is that women in such societies who bear sons enjoy higher say within households while those who do not succeed in bearing a son face social stigma and pressure at home, leading to domestic violence or divorce.

We studied how bearing one or more sons affects Pakistani women’s place within the household. We used pooled data from two rounds of Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) carried out in 2012-13 and 2017-18 and control for women’s individual characteristics (age, education, employment status, age difference with the husband, exposure to the electronic media), and husband’s education and household characteristics (family size, wealth, location and province of residence). We considered four types of household decisions: decisions regarding woman’s healthcare; decisions regarding social activities; household consumption decisions; and financial decisions. The corresponding questions that were asked from the interviewed women were are as follows: Who usually decides on female respondent’s health care? Who usually decides on visits to family or relatives? Who usually decides on large household purchases? and who usually decides what to do with money the husband earns?

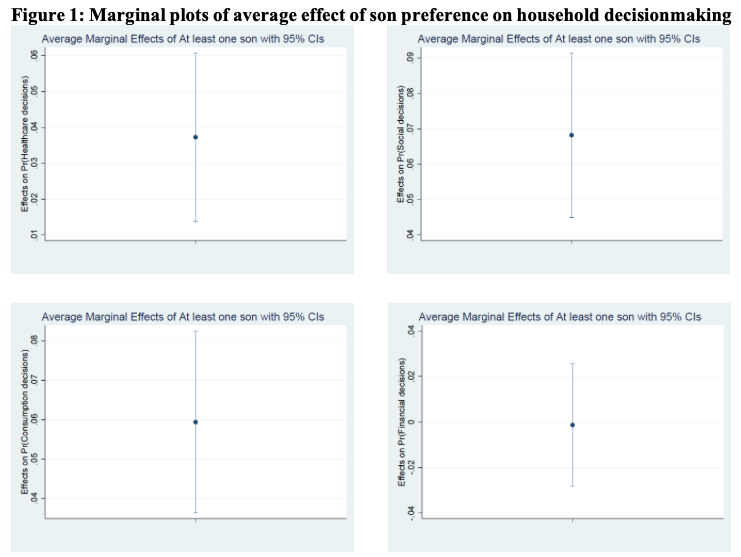

In our study, we found that women with at least one son make more household decisions either alone or jointly with their husbands compared with women without a son. Keeping other factors constant, the fact of women bearing one or more sons is associated with a 3.7 to 6.8 per cent increase in women’s say in decisions involving healthcare, social and consumption matters. Women’s role in financial affairs, however, does not differ significantly from women with no sons.

Based on these findings, it is clear that the improvement in women’s say in household decision-making resulting from bearing sons is decision-specific. Women’s say in everyday decisions increases to a certain extent as a result of bearing sons. ‘Everyday’, ‘routine’, or ‘mundane’ decisions correspond to less important social, healthcare, or economic matters not indicative of the existing power balance between the husband and the wife (for example visiting friends or relatives, seeing a doctor, buying a household item). This improvement, however, does not necessarily represent a greater bargaining power as her voice in financial matters does not improve. These ‘strategic’ decisions which involve money matters (for example who decides how much to spend) reflect the real source of power at home which inevitably remains out of women’s reach. Bearing sons does therefore not lead to significant economic empowerment.

Our analysis shows that a cause in the improvement of female decision-making may well be the disproportionate preference for a male child, which in itself symbolises the perpetuation of the unfavourable social status of women. This sheds a less glorious light on female participation in household decision-making as seen from the perspective of women’s empowerment. The findings, to a certain extent, explain why women in Pakistan and other countries in the South Asia show stronger preference for boys than do their husbands. The improvement in women’s bargaining power at home seems to come at a cost often paid by the girl child as differential preference for boys is associated with poor health and schooling outcomes of girls in Pakistan.

This blog has been adapt from Javed, Rashid, and Mazhar Mughal. “Have a son, gain a voice: Son preference and female participation in household decision making.” The Journal of Development Studies 55.12 (2019): 2526-2548.

This gives the views of the author and not the position of South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Male and Female Signage. Credit: Tim Mossholder, Pexels.