While we celebrate Bangladesh’s achievements in economic growth and poverty reduction, a growth-focused strategy does not serve Bangabandhu’s vision for an egalitarian society as it excludes and neglects many citizens. As Bangladesh’s economy thrives, Mathilde Maitrot and Joe Devine’s research finds there are persistent pockets of extreme poverty, some of which are getting worse, and that minority religious and ethnic groups are amongst the most deprived. This continued neglect risks further dividing Bangladeshi society.

While we celebrate Bangladesh’s achievements in economic growth and poverty reduction, a growth-focused strategy does not serve Bangabandhu’s vision for an egalitarian society as it excludes and neglects many citizens. As Bangladesh’s economy thrives, Mathilde Maitrot and Joe Devine’s research finds there are persistent pockets of extreme poverty, some of which are getting worse, and that minority religious and ethnic groups are amongst the most deprived. This continued neglect risks further dividing Bangladeshi society.

Reaching the ripe age of fifty, Bangladesh can look back with pride and look forward with cautious optimism. Since its independence, it has found a way to overcome huge challenges including decades of political uncertainty, constant climatic threats and frequent devastating cyclones and floods. Who would have predicted 50 years ago that today the life expectancy of Bangladeshis would match the world’s average? Who would have imagined that in 2021 Bangladesh would be held up as a global leader in poverty reduction? Who would have guessed that the country would be globally praised for the way it has hosted one of the world’s largest community of refugees?

Bangladesh has exceeded many expectations, and is today among the world’s fastest growing economies. In 2005, Goldman Sachs identified Bangladesh as one of the ‘Next Eleven’ (N-11), a group of countries with potential to become major global economic players. Its current status as a middle-income country rests firmly on its successful economic growth. Over the past 20 years at least, successive governments, even with different ideologies, have followed the mantra of growth and prosperity, expected then to ‘trickle down’ to lift millions out of poverty, create employment, build food security, and improve standards of education, health and social development. A vision of growth that promises inclusive prosperity.

During a recent event titled ‘Bangabandhu and Visions of Bangladesh’, co-hosted by the LSE South Asia Centre (with the High Commission of Bangladesh in the United Kingdom) to celebrate the birth centenary of the Founding Father of Bangladesh Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Professors Amartya Sen and Rehman Sobhan commented that the best way to honour Bangabandhu would be to build an egalitarian and secular Bangladesh. Professor Sen cited Bangabandhu himself: ‘the people of the minority communities are entitled to enjoy equal rights and opportunities like any other citizen.’ So, has Bangladesh’s successful trajectory of growth delivered on Bangabandhu’s inclusive and egalitarian vision?

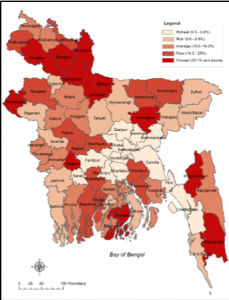

While Bangladesh can rightly boast many development successes, it remains the case that one in four citizens still live in poverty, with millions more surviving just above the official poverty line. Our recent research interrogates the geography and distribution of extreme poverty in the country. We found serious disparities: while more than half the citizens living in districts such as Kurigram and Dinajpur are extreme poor, in other districts such as Narayanganj and Munshiganj extreme poverty is almost non-existent. What this means in practice is that in Kurigram district for example, more than five out of ten people live on £16 per month or less. In other words, they cannot afford the cost of the most basic food and health needs. Map 1 below gives a sense of where those ‘left behind’, or ‘neglected’ — to use a more accurate word — live. Crucially, we also found that at a time of impressively high and steady economic growth (2010–16), the number of extreme poor actually increased in 24 of the country’s 64 districts! More than that, it is in the poorest districts where the number of extreme poor people is getting even higher, deepening the country’s pockets of exclusion, precarity and hardship. There is no point beating around this bush: the prevailing successful economic model neglects too many people. But who are these neglected citizens?

What has long been suspected can now be affirmed: there is a consistent pattern of deprivation amongst people who belong to minority ethnic and religious groups. There are persistent and strong associations between extreme poverty and marginalised ethnic and religious groups irrespective of the indicator used: income, education and health or access to basic facilities. However, our analysis is limited by the data available and we suspect a blind spot where other minority groups, not defined by religion or ethnicity, experience similar dynamics of exclusion and deprivation.

What has long been suspected can now be affirmed: there is a consistent pattern of deprivation amongst people who belong to minority ethnic and religious groups. There are persistent and strong associations between extreme poverty and marginalised ethnic and religious groups irrespective of the indicator used: income, education and health or access to basic facilities. However, our analysis is limited by the data available and we suspect a blind spot where other minority groups, not defined by religion or ethnicity, experience similar dynamics of exclusion and deprivation.

Beyond the place where people live and their ‘group’ identity, two other personal characteristics contribute to further marginalising people: gender and disability. Although counterintuitive, we find no stark difference in poverty between male- and female-headed households when we look at national level data. Differences however appear strongly when District level data is used. What this means is that that female-headship on its own is not a strong driver of extreme poverty, but it becomes powerful when intersected with other factors such as location or ethnic and religious identity. In other words, a female-headed household living in Bandarban or Kurigram is unlikely to be able to afford basic food. Our data suggests similar patterns when we look at people living with disabilities.

Why has Bangladesh’s successful economic growth not translated into better welfare outcomes for these marginalised groups? And why has the situation of these minority groups got worse over time? Poverty is not a natural phenomenon. It does not exist in some sort of vacuum, not in Bangladesh, not anywhere. Social injustices are not only rooted in unequal access to (un)fair markets but deeply entrenched within social institutions that exploit people’s vulnerabilities and often limit what they, and their children, can aspire to and achieve. For this reason, economic and growth-based solutions alone cannot solve deep-rooted social challenges such as marginalisation because the disadvantage experienced by those marginalised is not just economic. Moreover, our data suggests that a reliance on economic growth alone, i.e., pursuing development business as usual, risks creating an even more divided and unequal society with minority groups further alienated.

In her seminal work on justice claims, the American philosopher Nancy Fraser argues for a transformative political agenda capable of addressing the root causes of neglect and injustice, as opposed to looking at their consequences or impacts. This agenda requires both a politics of recognition that acknowledges differences and a politics of redistribution — the kind of politics Bangabandhu hinted at in his vision of an egalitarian Bangladesh. Can public policy help make this vision a reality? Yes it can, but only if it confronts the powerful others who have long benefitted from the current status quo. Yes it can, if it urgently addresses the dearth of data about ethnic minorities and marginalised groups in order to build the evidence base needed to develop tailored and targeted policies. We are two friends of Bangladesh looking from outside at a country we love, and hope that over the next 50 years, Bangladesh will surprise us again and build its own path towards a more inclusive society where all citizens’ rights are equally respected and fulfilled.

*

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and not those of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics & Political Science.

Banner image © Md. Golam Murshed, ‘A family, Bandarban, Bangladesh’, Unsplash.

The ‘Bangladesh @ 50’ logo is copyrighted by the LSE South Asia Centre, and may not be used by anyone for any purpose. It shows the national flower of Bangladesh, Water Lily (Nymphaea nouchali), framed in a design adapted from Bangladesh’s dhakai & jamdani textile weaves. The logo has been designed by Oroon Das.

*