Sex-specific birth-spacing is one potential manifestation of the disproportionate preference for sons in traditional Asian societies. Dr Rashid Javed and Dr Mazhar Mughal discuss their research evidence from Pakistan to show that Pakistani women attempt to conceive again soon after a girl is born. They argue that the subsequent shorter birth intervals lead to higher demand on the mother’s body and greater health risks for mother and child.

Reducing gender bias and achieving gender equality is one of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 05). Son Preference is a form of gender bias that persists in many parts of the developing world. The phenomenon has a number of economic, social and cultural causes. In the absence of insurance markets and social safety net programmes, sons are perceived to be the households’ major economic assets, as they take up family businesses and insure parents’ old-age finances.

In contrast, daughters are considered an economic burden for the household: parents must save for their dowry, and they leave home after their marriage to join their husband’s household. As a result, women who bear sons often enjoy high status at home. In a previous project, we found that son preference has a direct effect on the status of women at home. Women with one or more sons have more say in household decision-making, while women not bearing sons face social stigma and pressure from the family.

Couples continue childbearing until the desired number of sons is achieved. Couples with only daughters and no sons may therefore go for the next child after a shorter interval. Shorter birth spacing leads to higher demand on the mother’s body and affects the nutrition and health of the existing children. As a result, there is higher risk of disease, malnutrition and mortality, particularly among girl children.

In a recent study, we examined the son preference – birth spacing relationship in Pakistan. This country is an interesting case study, being a populous, Muslim-majority country. Son preference is widespread in Pakistan, even though, unlike in other son-preferring Asian countries such as China and India, sex-selective abortion is not commonly practiced. The reproductive effects of son preference are therefore bound to be reflected in differential birth stopping and spacing patterns.

We tried to find answers to a number of unexplored questions: Does son preference affect birth spacing? Does it vary by the order of birth when sons are born? Has this relationship evolved over time? Does son preference increase the probability of risky births (those taking place within 24 months after the preceding birth)? The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a minimum 24-month gap between two consecutive births to maintain the health of the mother and the child.

We employed data from three rounds of the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS), PDHS 1990-91, 2006-07 and 2012-13. We restricted our sample to those women who have completed their childbearing with at least one child. We controlled for women’s individual characteristics (age, education, employment status, age difference with the husband, exposure to the electronic media), husband’s education, and household characteristics (family size, wealth, location and province of residence).

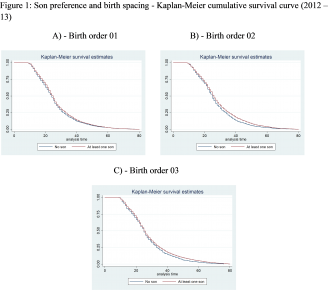

We found a strong relationship between son preference and subsequent birth spacing (Figure 1). The effect is statistically significant at early birth orders, and seems to dissipate beyond the third birth interval. Women with a first-born son are 10 –13% more likely to delay the second birth compared to women whose first child is a girl. Likewise, women with at least one son out of the first two children are 10 –15% more likely to delay the third birth compared to women without a son. In the same vein, we find that women whose first two children are boys are 13 –17% more likely to delay the next birth compared to women both of whose first two children are girls. We also checked the role of son preference on the last birth interval. We found that all-son women are 14 –18% more likely to delay their last birth compared with corresponding women with one or more daughters.

We also found son preference to be associated with risky births. Women with at least one son have lower probability to have subsequent birth spacing of less than 18 or 24 months.

Another indication of this differential spacing is found in the couples’ contraceptive prevalence as women with one or more sons who do not report their fertility to be complete are found to be more likely to use contraceptives compared to women with no sons.

Source: Authors’ calculations using PDHS 2012 –13

To summarise, we found conclusive evidence suggesting that Pakistani couples stay away from contraceptive methods and shorten their subsequent birth spacing in order to obtain the desired number of sons. This manifestation of son preference has important consequences at the national level. Connubial bliss may indeed require a son or two, but the disproportionate preference for sons that it entails affects the country’s demographic transition by hampering efforts to control rapid population growth, reduce high incidence of child and maternal mortality, and improve health outcomes.

Pakistan has one of the highest child and maternal mortality rates in Asia. Mortality among girl children is especially high, and may in part result from the risky fertility behaviour associated with excessive preference for boys. The country seeks to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal of bringing the incidence of maternal mortality to below 70 deaths per 100,000 live births and under-5 mortality to below 25 per 1,000 live births by the year 2030. Policy measures and awareness campaigns that promote gender equality in the country can help lessen the occurrence of risky births, thereby not only lowering the risk to both mother and child’s life but also improving their health outcomes. Tackling pervasive desire for sons can therefore be an important ingredient of any successful policy action targeting maternal and child health.

This blog has been adapted from Javed, Rashid, and Mazhar Mughal. “Preference for boys and length of birth intervals in Pakistan,” Research in Economics 74.02 (2020): 140 –152.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Banner Image: Photo by Luis Galvez on Unsplash.