As the ruling Awami League pushes forth with its vision of a ‘Smart Bangladesh’ by 2041, focusing on increasing digitalisation and reliant on widespread subscription, Ratan Kumar Roy asks a crucial question: can a ‘smart’ policy alone bring about societal change, or does it require something more?

A short video-clip of the dramatic collapse of a dais — where the General Secretary Obaidul Quader of the ruling Bangladesh Awami League (AL) was talking about visions of a ‘Smart Bangladesh’ on 6 January 2023 — went viral. Hundreds of GIFs were created and circulated, and social media users made hilarious Reels and TikTok videos mimicking the moment of embarrassment. The GIFs served the purpose of the political opposition because of a coincidence of the crumbling of the stage and the utterance of ‘Smart Bangladesh’, thus gaining a symbolic significance, if inadvertently.

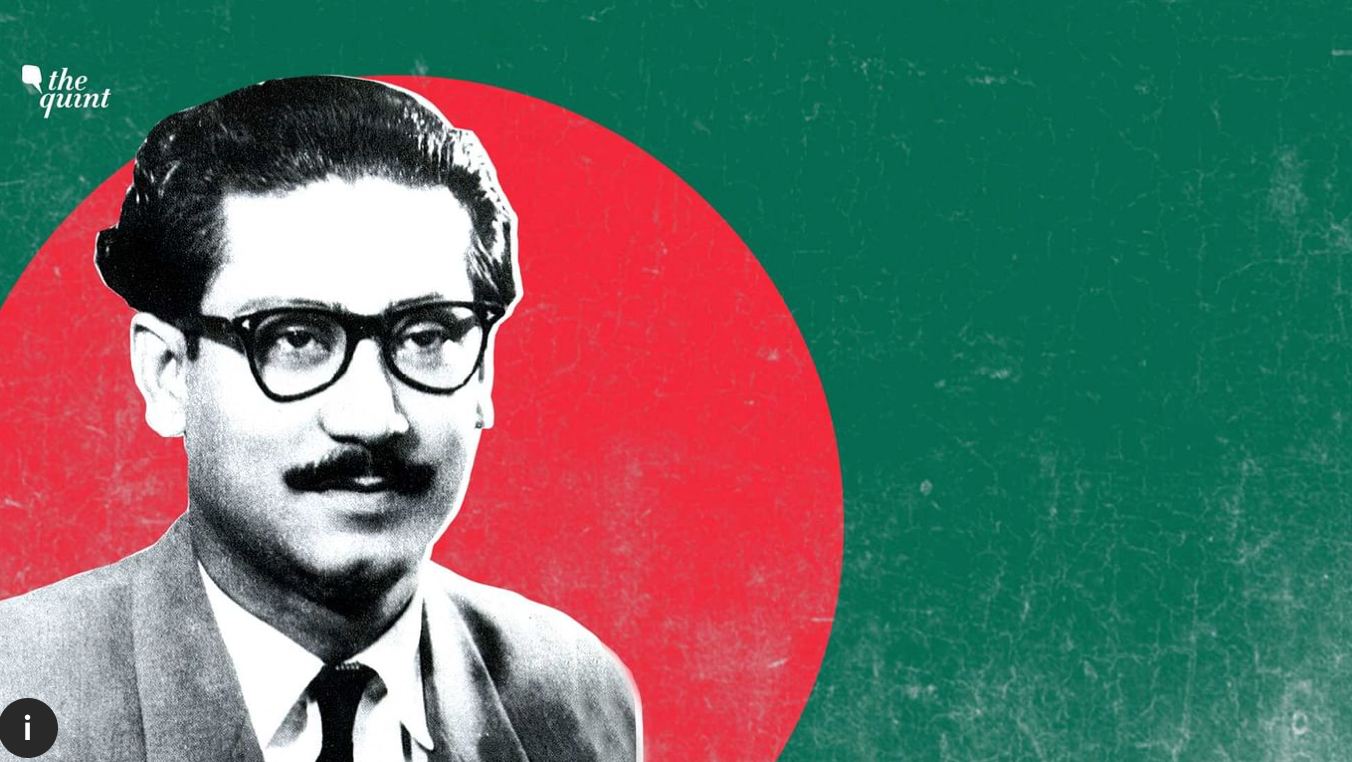

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina introduced the idea of ‘Smart Bangladesh’ on 12 December 2022, during her speech at Digital Bangladesh Day, unveiling her vision of making Bangladesh a developed nation by 2041. The project — ‘Smart Bangladesh Vision 2041’ — is built on four pillars: smart citizen, smart economy, smart government, and smart society. No wonder the narratives on and around ‘Smart Bangladesh’ are essentially techno-centric. But it appears that a critical element that has gone missing in this, one that would facilitate holding these pillars together, is Smart Politics.

In December 2022, Sheikh Hasina instructed the Bangladesh Chhattra League (BSL), the student wing of the Awami League, to build Smart Bangladesh. A month on, in January 2023, the stage collapsed at the University of Dhaka whilst urging BCL leaders and activists to work for Smart Bangladesh. In the following months, complaints were filed against BCL leaders for torturing students at various university hostels. This series of incidents made it pertinent to seek a smart political culture, even if not in practice but at least in thinking. Can ‘smart thinking’ be the bottom line of this mega vision? Here, I review what is outlined in ‘Smart Bangladesh’, and its genealogy.

*

The Awami League came to power in 2009 with a ‘Vision 2021’ centring around Digital Bangladesh which aspired to provide better services and governance through improved Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). To achieve a Digital Bangladesh by 2021, the government has since put tremendous effort into developing infrastructure and capacity in ICT. The vision was to connect citizens and accelerate service delivery, jobs, efficient governance, and an economy based on digitalisation. Expanding internet connectivity, increasing digital services and using ICT for economic sectors help conjure an image of a thriving development. Establishing around 40 HighTech parks, thousands of Digital Centres across the country providing hundreds of services and facilities, making a sizable export value for ICT, creating freelancers and 2 million ICT-based jobs, and installing Bangabandhu Satellite 1 are some of the visible successes of the Digital Bangladesh vision.

However, other aspects of the digital regime like the Digital Security Act (DSA) 2018 evoke apprehension and frustration among citizens. Controls, contestations and conflicts at various levels reveal the pitfalls of digitalisation, and the DSA has been implicated in muzzling ‘troubling’ voices of the people by the state. Between the development discourse on one hand, and digital control on the other, the government has adopted ‘Vision 2041’ as a continuation of ‘Vision 2021’ to provide impetus to the development dream of the nation, a strategy towards Smart Bangladesh while maximising the possibilities of the 4th Industrial Revolution (4IR). The claim is to be inclusive, and imagine ‘Smart Bangladesh’ beyond mobile and internet technology. Therefore, the four pillars are crucial for this vision.

The ‘Smart Bangladesh’ project aims to make citizens capable of using technology to improve their quality of life. In an App-based life, they buy-sell or fill out forms, and have an enhanced civic participation online. Smart Government is a data-driven public administration system that will rely on technology at both ends: policy-making and policy implementation. Transparency, efficacy and effectiveness for service delivery to citizens will be ensured with the availability and dependence on Apps, data analytics, and the Internet of Things (IoT). Smart Economy will be built on the bedrock of 4IR, emphasising smart supply and production chain management, and the use of Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Finally, the Smart Society will be a data-driven, inclusive society where access will be easier, participation will be more, and costs will be reduced. Such a ‘smart society’ will be sustainable and futuristic in that it will address socio-environmental challenges.

But in this moment of excitement about the inception of a digitally enabled ‘Smart Bangladesh’, less is being discussed about the cost of digital dependence. Moreover, it hardly creates a new imagination beyond the digital-centric production and institution. For example, it outlines a gradual implementation of digital skills development, e-commerce and market, e-agriculture, digital job platforms, smart and paperless administration, digital education and pedagogy, e-health, and medical services; what is missing is smart thinking for transforming the political culture often found responsible for making the system dysfunctional from within.

The questions ahead for the people and policy-makers are: will there be any mechanism to reduce corruption and bureaucratic red-tapism in the system? Can ordinary citizens be assured that a handful of people will not find a smart way to launder money from the country to various foreign destinations? Will the country have a peaceful atmosphere ahead of its elections, where confronting political groups will not spread violence on the street?

Current evidence in the everyday socio-political landscape of Bangladesh does not provide a positive view on these questions. Opposition parties are stuck with old versions of political activism and practices. BCL leaders are often involved in rape, highjack, torture, ragging students and extortion from businesses and others. The media’s narrowcasting lens focus on creating hype about political clashes and conflicts ahead of elections. The political party in power is getting tired of controlling the numbers of aspiring leaders; the General Secretary of the AL had to urge that they need more smart workers but not leaders for achieving ‘Smart Bangladesh’.

Uncertainty and volatility in the political climate cannot be convenient for the realisation of a ‘Smart Bangladesh’. It requires making politics smarter with smart thinking at various levels. Beyond the political culture, achieving a Smart Bangladesh would be possible if citizens themselves also become smart: for instance, even after 20 years of setting up automated traffic lights in Dhaka city, people in the city have hardly gotten used to following traffic signals. Air pollution level in Dhaka is 14+ times higher than WHO-recommended Air Quality Index value; people often litter and throw rubbish randomly with no effort to keep public places clean. All these are real-life scenarios of a capital city where use of smartphones and internet penetration is relatively high. Therefore, it is not far-fetched to argue that without penetrating ‘smart thinking’ amongst the people, and ‘smart imagination’ in the thinking of the new generation, a digital-centric vision of smart Bangladesh may not succeed.

In a country where the idea of digital connectivity is borrowed from the West and improvised for a nation dependent on technology produced in China, a digitally-oriented, techno-centric, data-driven ‘Smart Bangladesh’ must foster originality of ideas and imagination for meaningful innovation for a better future. At heart is the need for ‘smart politics’ to be inserted in this scheme, with smart thinking disseminated into the social psyche.

Effective ‘smart politics’ can be achieved by curbing partisan nepotism at various levels of bureaucracy and politics, and ending political control over rule of law. Political parties in power should not have undue control over the administrative and executive organs of the state to crack down the political oppositions. At the other end, those not in power should not rely on to violence, unrest and unconstitutional ways to oust governments. ‘Smart politics’ should enable party leaders and activists to move beyond the violent politics that has till now undermined the establishment of a stable, steady and robust democracy. Such a ‘smart politics’ would enable smart governance where there is transparent correspondence between the legislation, judiciary and executive, citizens are served by a corruption-free administration and judiciary, enhancing accountability. It will also lead to a truer decentralisation of power where better healthcare and education facilities are not urban-centric considering more than 60 per cent people live in rural areas in Bangladesh.

The genuine pursuit of ‘smart thinking’ for citizens is essential for making sure that technology is not outsmarting the people. ‘Smartness’ should not be imposed from above on people — it should align with varying levels of tech-savviness, digital literacy and access to technology. It is how smartly the government address the challenges of everyday life, defying digital divides and new kinds of inequalities. With a smart mindset that makes people responsible about self-conduct, passionate towards national development and motivated towards national values and human well-being, a vision of ‘Smart Bangladesh’ may thrive.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Anne Nygård, 2022, Unsplash.