The #MeToo Movement has resonated variously across the world, with differing impacts. Amidst all this was published LoSHA, a crowd-sourced list of alleged sexual harassers in academia by an Indian law graduate studying in the USA. Srishti Ray looks at the debates among Indian feminists surrounding #MeToo-LoSHA, and whether such global movements continue to fail to include historically marginalised groups in India.

The #MeToo Movement is a perfect example of the positive impact of social media. The movement, initially begun by Tarana Burke more than 10 years before it gained widespread global recognition in 2017, brought victims closer via social media, giving them a much-needed voice. This voice of protest demanding justice helped survivors share their side of the story, bringing down some very influential and powerful men from their sky-high seats.

Importantly, it has helped change legislations across the world. For example, states in the USA have banned Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) that cover any form of sexual assault. This was the direct outcome of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein’s Assistant Rowena Chiu’s complaint about being made to sign an NDA where she was not even allowed to disclose to her own family that her boss exposed himself to her, repeatedly, for over twenty years.

The #MeToo Movement reiterates the age-old fight against sexual harassment. It helps us to see issues through the victims’ lens, thereby making it more powerful and effective. The use of the #MeToo hashtag across the world has shown that this is a systemic issue where survivors — mostly women — have been systemically subjugated and ‘kept in their place’. It makes the larger public realise that it is not one person turned bad, but our fathers, neighbours, uncles, colleagues, bosses — the seemingly ‘good guys with a happy married life’ too.

But Martha Nussbaum in her Citadels of Pride: Sexual Abuse, Accountability, and Reconciliation (2021) rebuts this proposition. A pre-eminent philosopher known for her writings on justice as a philosophical debate, she argues that due process of law is being overwhelmed by the anger that is being channelled by the #MeToo Movement. Nussbaum acknowledges sexual harassment at the workplace as a systemic issue especially since there is no stable or uniform set of rules against them, and thereby an ‘asymmetry of power’. But her principal argument is that making the #MeToo Movement a social (rather than legal) issue means that justice is not being achieved through legal institutions that are impartial but by naming and shaming (an ‘apocalyptic vision’), which is unacceptable in her opinion.

In an interview with The New Yorker last year, Nussbaum said that she is against bringing back shaming as a punishment at the penalty stage: branding a person with an act, a single act, confuses the act with the person irrevocably. The people, via social media platforms, start acting like the jury and the penalty administrator, which is everything law and justice stands against.

I agree with Nussbaum on the point of crowd-administered penalty being an evil beyond morals. Sifting evidence before shaming a person for a crime they did (or did not) commit is essential. In case of Weinstein, for example, they tried to look for people to sit on the jury who did not already have a pre-conceived notion about him or the allegations. This, in substance, is very important; the ends of justice can only be served fairly when the two parties are brought to one room and heard without prejudice.

*

The impact that the #MeToo Movement has had in India unsurprisingly did not reach the historically marginalised sections of the population. In 2017, Raya Sarkar, a law student at the University of California-Davis of Dalit origin, published a crowdsourced ‘List of Sexual Harassers in Academia’ (widely known as ‘LoSHA’) on Facebook. This was a long list of academics who, she alleged, had sexual harassed their students. Two opposing sides spawned the debates that emerged out of LoSHA. On one side, some feminists applauded women in academia for finally being courageous enough to break their silence; on the other, accusations arose that LoSHA had no veracity, and went against due process of law. Surprisingly, and as commented by Rupali Bhansode (2020), feminists against LoSHA limited their voice to speaking only about ‘due process’ instead of extending it to criticising the lack of Dalit testimonies.

Sharmila Rege, in Writing Caste/Writing Gender: Reading Dalit Women’s Testimonios (2006), discusses why Dalit testimonies are to be read as ‘testimonio’, a ‘first-person talking’ narration as they recount a life-changing experience. Such testimonios, according to Rege, brings a delicate balance between caste and gender, and how it is shaped by patriarchy, and helps us better understand this both inside and outside the community. Caste-based sexual violence in India is not only a repeated occurrence but also one that has been conveniently overlooked for centuries. Several feminists spoke up against due process but there is a blatant disregard for Dalit testimonies.

Accessibility obviously matters when we talk about social media-run movements like #MeToo. Sure, the pros of such movements where women finally get to have a voice is tremendous and empowering, but marginalising the already marginalised solves one problem while creating another.

Intersectional feminism signifies how a system of oppression impacts differently on different people based on their race, caste, class, etc. It is therefore pertinent to understand that patriarchy impacts women of different castes in India differently. And here comes the concept of ‘casteist patriarchy’. Dalit women being exploited sexually has caused major hue and cry on several earlier occasions in India, and has led to changes in the Indian legislation. For example, the gang rape of a Dalit woman named Bhanwari Devi by upper-caste men in the 1990s led to what we now know as the Vishaka Guidelines (from the Vishaka & Ors vs State of Rajasthan & Ors 1997 lawsuit). But neither the judgement nor the Guidelines included consideration of Bhanwari Devi as a Dalit woman, and how it may have shaped the heinous act. By overlooking caste identity, we are looking at all such issues through the lens of gender alone, going against the very definition of intersectional feminism.

*

Coming back to LoSHA, its compiler made public the fact that most women who helped her compile the list were, like her, DBA (Dalit/Bahujan/Adivasi) women themselves, who trusted her enough to share their stories with her. A group of frontline feminists came out with the statement that this delegitimised the struggle to achieve due process, and made ‘their’ tasks as feminists more difficult. Thus, they wanted the List to be withdrawn as soon as possible. The hostile underlying tone suggested that women who courageously came out with their stories were not feminists, because their opinions did not match those of mainstream feminists, who were somehow the ‘correct’ ones. Understanding this divide is essential because this is not just a difference in opinion between two parts of the same family; rather, it clarifies that feminists are not a single body joined in their bones by a synovial fluid of sisterhood.

Growing up in a middle-class Hindu Bengali family, caste was never a topic that was brought to dinner-table discussions in my home. As and when I started reading up on matters like caste and gender, I began to realise how many ideas that we grew up with need to be rejected and started anew. Understanding intersectional feminism is one such idea that needed re-learning, and is still a work in progress. Understanding how someone’s social or political identity can marginalise them along with their gender is complex yet crucial.

*

So, was the #MeToo movement a voice only for the urban élite? The long and short answer is, Yes. But it is more complex than just that. Even though several Dalit women in India were at the forefront of the fight against sexual harassment, they are now left to wonder who the ‘Me’ in #MeToo-India is? A plea for #MeToo to be inclusive and acknowledge the suffering, adversity and strength of women who are Dalit, rural, and non-English speaking, whose experiences remain peripheral in the mainstream discourse, has never been more important than it is right now.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

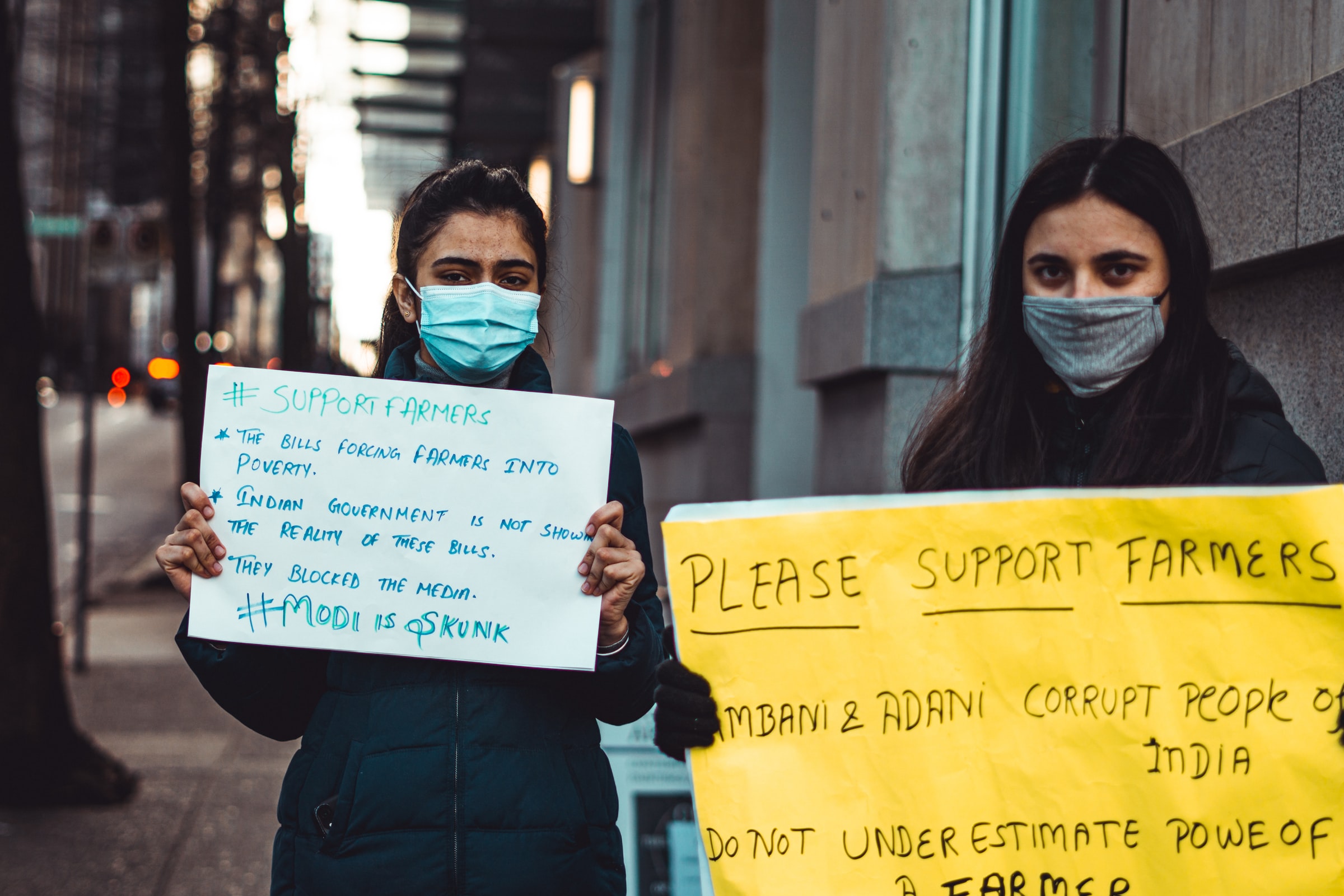

Banner image © Mihai Surdu, 2017, Unsplash.

*

I am proud and delighted to read your excellent article following the footsteps of your Father.

I would cherish to such articles of yours in the coming days.

With Love and All Best Wishes,