Clean cooking lies at the heart of clean air for the people. In this post, Bishal Bharadwaj considers the challenges to the adoption of clean cooking in Nepal, the prevalence of traditional practices, the challenges of uneven development and insufficient infrastructure, and how some of it may be mitigated through customised policy and investment to achieve developmental goals.

Nepal’s diverse topography presents a unique challenge for ensuring access to energy. Since the establishment of democracy in 1951, three policies have significantly reshaped Nepal’s socio-economic context: the successful reduction and planned eradication of malaria, which triggered a significant migration of people towards the southern plains; construction of the East–West (Mahendra) Highway in the southern plain, which enhanced connectivity and accessibility across different regions; and increased southward migration.

Planned development projects began in 1956, but they have often been biased towards areas represented by influential political leaders, leading to an imbalance in development and infrastructure in the country. Even after several decades, significant disparities of physical infrastructure and socio-economic conditions remain across different areas; for instance, the central and mid-western regions have higher road density compared to the far-western regions. As we move westward, the intensity of monsoon rainfall decreases, posing a different set challenges in farming. As such, collectively, the mid- and far-western regions tend to exhibit higher levels of poverty compared to other areas. Deprivation tends to increase as one moves towards the northern side of the country.

*

Despite being one of the first countries in Asia to harness hydroelectric power, the majority of households in Nepal still rely on solid or dirty fuels for cooking. Various programs (subsidies, social mobilisation) have been implemented to mitigate this but progress in achieving widespread access to clean cooking has been slow and uneven. For example, cow dung use (for fuel) is 2.5 times the number of households using biogas. This raises a fundamental question: what are the underlying factors that impact energy access in Nepal?

Clean Cooking in Heterogenous Contexts

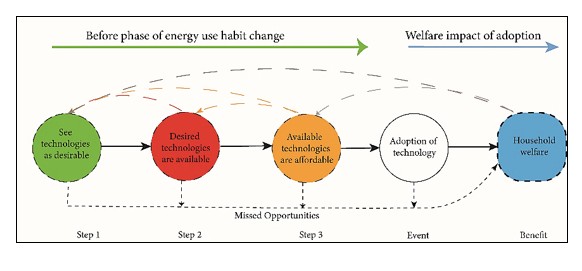

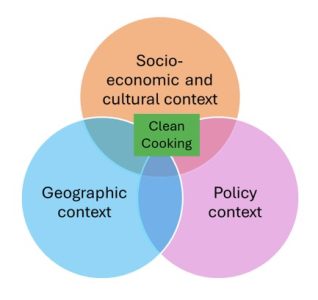

Using clean fuels for cooking is a household decision but a variety of external contexts, and policy impact, influence the demand for, availability and affordability of clean cooking technology (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Influence of Context in Energy Access © Bharadwaj (2022).

Figure 2: Factors Shaping Transition to Clean Cooking in Rural Nepal Energy Access © Author.

Demand for Clean Cooking

Cooking practices are an integral part of rural livelihoods, with firewood serving as the cornerstone of social cooking traditions. Firewood holds great cultural significance as it is deeply intertwined with traditional practices and rituals. In remote areas, access to goods (including clean cooking services and fuel) becomes both costly and challenging. Households have a traditional practice of producing their fuel goods through everyday livelihood practices. For instance, they collect leftover branches and twigs from cattle fodder and use it as cooking fuel to manage waste (otherwise a challenge to manage in rural settings) and fulfil energy requirements. The ash from firewood also has multiple uses, such as in pesticide and for cleaning utensils; thirty goods and services have been linked to firewood use in rural households in Nepal.

Without change in the overall/wider context, households continue to rely on firewood to meet their diverse needs, even for other purposes. Notably, firewood was ranked as the best cooking fuel in six out of nine criteria in Nepal. Traditional cooking methods that utilise firewood, including agricultural waste, offer several advantages to households. Apart from being readily available, people have the skill to construct and modify the mud-stoves as needed. Thus, a combination of economic, cultural and practical factors associated with firewood use contributes to its continued prominence in rural areas.

Availability of Clean Cooking

The adoption of clean cooking is influenced by the context in which they are implemented. Each clean energy technology requires certain conditions to be met for it to serve effectively as a cooking fuel in the household. For instance, cold climate creates an anaerobic reaction in biogas, posing a challenge to the suitability of biogas as a cooking fuel in mountain areas.

Availability of clean cooking fuels at the village level is influenced by various restrictions that may hinder access. Photo 1 — of yaks carrying Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG) cylinders — shows how lack of proper roads exacerbates the difficulties in using LPG regularly. Maintenance facilities and technicians are barely available in these areas, and the absence of grid electricity makes the choice of electric cooking impractical. All these factors contribute to the challenges surrounding the availability of clean cooking fuels.

Photo 1: Yaks Carrying LPG Cylinders to Namche Bazar © Rabin Raj Niraula; for further information, see below.

Where conditions are suitable for biogas in warmer areas, there too adoption is not guaranteed. The construction of a biogas plant for a household requires space and a sufficient supply of bio-feedstock, particularly cow dung, which can be restricting factors for households with limited space or those living in rented properties or without access to a secure supply of bio-feedstock. As for electric cooking, while it may be a viable option for grid-connected households, the unreliability of grid electricity and frequent power outages discourages households from taking the risk of relying solely on electric cooking.

Affordability of Clean Cooking

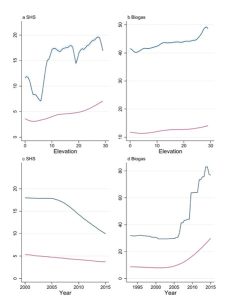

Context also plays a significant role in determining the affordability of clean cooking solutions. The value of money varies across different villages in Nepal, and households in remote districts often pay twice as much as those in accessible areas for the same goods and services. One of the major costs is transportation: the mode of transportation, the number of points where goods need to be unloaded, stored, repackaged, loaded again, and transported, as well as the commission charged by each agent at each point. This cost disparity across Nepal, and even from village to village, directly impacts the affordability of adopting renewable energy technologies (RETs). To illustrate, households in the Khumbu region have to pay NRs 15,000 (US$113 approx.) for an LPG cylinder, ten times the NRs 1,500 (US$11 approx.) in the capital, Kathmandu. Biogas cost also increase with elevation.

Subsidies do not necessarily adjust to account for these variations in cost, and installation costs offset by subsidies is lower for people in remote areas (see Figure 3). Not having a minimum capacity requirement for subsidised renewable technologies means households adopt low-capacity solutions that may not support electronic appliances like electric cooking.

Figure 3: Change in Cost and Subsidy over Elevation and Time © Bharadwaj et al. (2022).

Achieving Clean Cooking Targets in Nepal

Merely focusing on replacing cooking fuels without considering the integral role of cooking practices within livelihoods is likely to result in limited success. Therefore, when addressing energy access challenges, it is essential to recognise the multifarious cooking practices and the diverse benefits that traditional methods (such as those involving firewood) offer to households in Nepal.

This spatial inequity in renewable energy subsidies is just one indication of how policies could hurt remote communities that require additional support. These limitations and disparities in infrastructure and availability of clean energy and other social support hamper the adoption of clean cooking technologies in remote regions. The higher costs associated with transportation and installation, combined with lower subsidy coverage, present significant financial barriers for households in these areas. Addressing this affordability gap requires targeted interventions that account for regional cost variations and provision of appropriate financial support to make clean cooking solutions more accessible and affordable for households across Nepal.

To expedite the adoption of clean cooking in the heterogeneous context of Nepal, the federal government should provide result-based funding to the local government’s chosen contextual interventions on clean cooking — for example, where micro-hydro plants can reliably supply electricity for electric cooking and may choose to subsidise it. This motivates local governments to mobilise resources to benefit from federal support.

A decentralised approach has the potential to drive effective and tailored clean cooking initiatives throughout Nepal. The diverse topography boasts a range of clean cooking technologies such as electric cooking and biogas, an opportunity local governments can tap to accelerate sustainable clean energy transition.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

Copyright information for Photo 1 © Rabin Raj Niraula. This photograph has been used with permission by the author. it may not be used by anyone else without prior written permission of the photographer.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Sebastian Pena Lambarri, Stupa at Namche Bazar, Nepal, 2018, Unsplash.

*