This June, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a decision that could have important impacts on the rights and representation of minorities. Using new research, Paru Shah, Melissa Marschall and Anirudh Ruhil find that the number of cities covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act with at least one African-American city council member increased by 82 percent between 1981 and 2001. They also argue that coverage by the Voting Rights Act seems to amplify the effects of minority voting strength, council size, and electoral structures in cities.

This June, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a decision that could have important impacts on the rights and representation of minorities. Using new research, Paru Shah, Melissa Marschall and Anirudh Ruhil find that the number of cities covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act with at least one African-American city council member increased by 82 percent between 1981 and 2001. They also argue that coverage by the Voting Rights Act seems to amplify the effects of minority voting strength, council size, and electoral structures in cities.

Given that blacks were historically excluded from officeholding, it is generally thought that by removing barriers to voter participation and candidacy, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) would have its most significant effect on increasing not only black voter participation but also black candidates’ access and ascension to elected office. At the same time, the conditions that led to the passage of the VRA – voter discrimination and intimidation, vote dilution, as well as restrictions on educational and employment advancement for blacks – meant places covered by the VRA’s Section 5 had considerable ground to make up. Section 5 prohibits election practices or procedures in states with a history of discriminatory voting practices until these new procedures have been subjected either to an administrative review by the United States Attorney General, or after a lawsuit before the United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

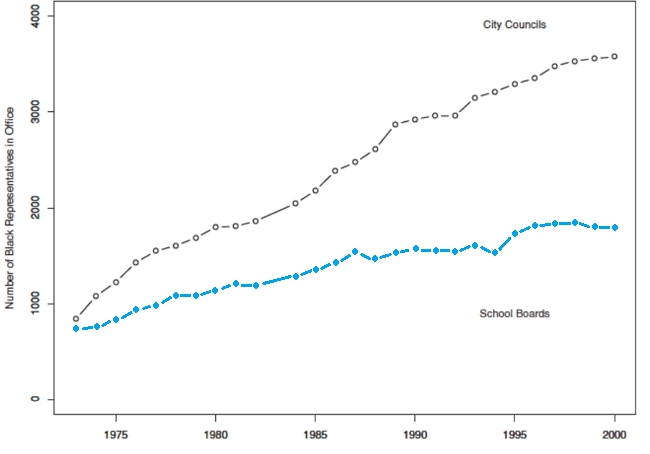

Anecdotally, some have argued that we have achieved the goal of increased representation. In his critique of the continued value of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, Chief Justice Roberts noted that many of the same cities witness to the violence during the civil rights movement are now governed by African-American mayors, and concluded that “there is no denying that, due to the Voting Rights Act, our nation has made great strides.” It is certainly true that over the past several decades racial and ethnic minorities have secured elected office at all levels of government: between 1972 and 2000 the total number of black elected officials in the United States increased by roughly 300 percent, from 2,264 to 9,040, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Black Representation on City Councils and School Boards (1973-2000)

Missing, however, from the arguments surrounding the reauthorization debate was an examination of the VRA’s role (as opposed to that of changing racial attitudes or black population growth) in ensuring black candidates win elected office. Our research is one of the first to take a “big picture” look at a large sample of city councils over time to see where African-Americans are making gains, where they are adding or losing seats and whether they have ever been elected in the first place.

How could VRA coverage impact the likelihood of black representation? On the one hand, Section 5 coverage could indirectly thwart attempts of voter dilution by limiting the ability of cities to change their voting rules from those that relied on compact electoral districts to those that required candidates to compete city-wide. Thus, in ensuring a cohesive minority-voting block, the VRA could help ensure that the conditions encourage minority residents to seek and win local elected offices were in place, thereby increasing minority representation.

On the other hand, the VRA could operate directly on black gains in representation by changing the nature of the places covered. For example, an explicit goal of the civil rights movement centered on black enfranchisement and political participation in the South, particularly in those states eventually covered by the VRA. Civil rights groups worked relentlessly to register, mobilize and empower black voters throughout this period. This activist infrastructure and the fact that blacks in the South were politically motivated and increasingly activated, means that voters in covered places would more effectively translate their votes into elected seats. We argue that similar contextual effects influence the ways in which governing institutions, black resources, and white voters matter in Section 5 covered jurisdictions.

To explore the questions of where, when and how the VRA contributed to gains in black representation, we constructed a dataset spanning 25 years (1981-2006) of cities across the United States. Examining black representation on city councils, our analysis focused on two questions: first, how did VRA coverage impact the likelihood of any black representation on a city council, and second, how did VRA coverage impact the total number of black council members elected to office?

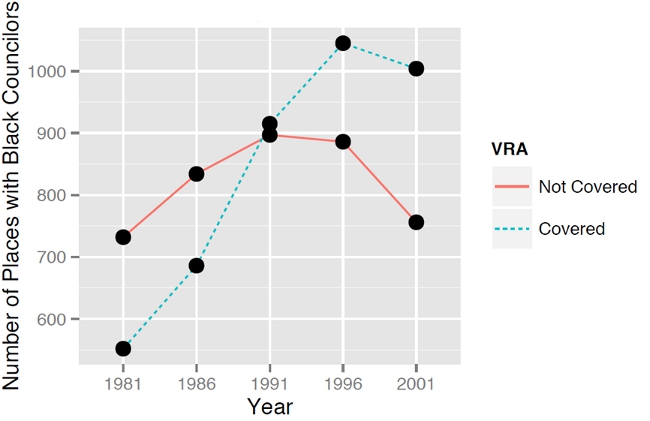

We found that the VRA continues to be a significant force in ensuring gains in black representation. First, most of the gains in black representation occurred in covered jurisdictions. As Figure 1 illustrates, between 1981 and 2001, the number of cities covered by Section 5 of the VRA with at least one African-American city council member increased from 552 to 1,004 – an 82 percent change. The number of cities not covered that had at least one African-American city council member increased just 3.3 percent – from 732 to 756.

Figure 2 – Number of cities with black councilors by VRA coverage 1981 – 2001

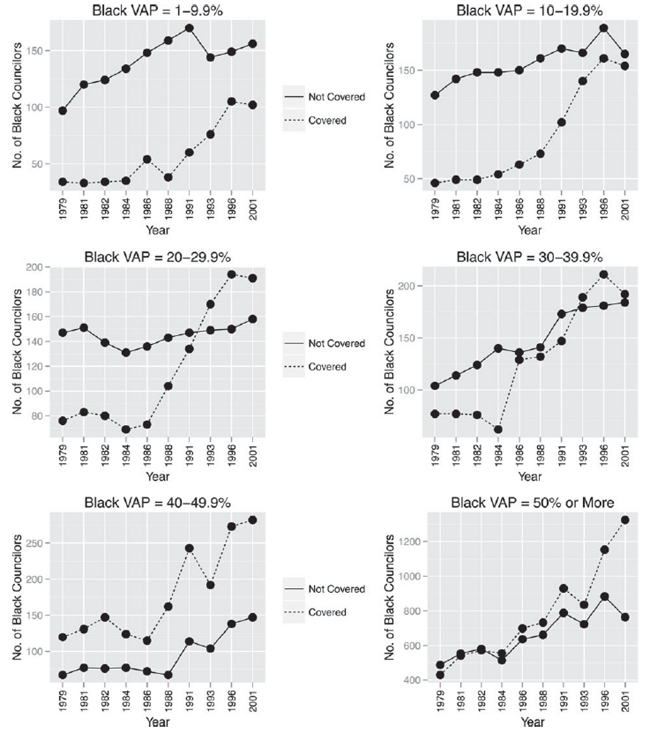

Figure 3, below, clearly demonstrates that population size matters. Black representation is more likely in places with majority (greater than 50%) black populations, regardless of VRA coverage. However, the rate of growth in representation was greater in covered cities with more average (10-30%) black populations. We also found that coverage did indeed change the nature of the cities. Specifically, coverage seems to amplify the effects of minority voting strength, council size, and electoral structures. Thus, whereas other research has also demonstrated that each of these factors is important for minorities seeking elected seats, our findings suggest the coverage reduces the challenges posed by smaller black voting populations, smaller legislative councils and at-large or mixed electoral systems.

Figure 3 – Distribution of Black Councilors by year, Section 5 coverage, and percentage of Black voting age population (VAP)

Note: Total number of black councilors is displayed by percentage of the city’s black voting age population (VAP) and Section 5 coverage. Data comes from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Roster of Black Elected Officials and thus constitutes the full population of places in the U.S. with black representation on city councils for any particular year.

We also found important over-time effects of the Voting Rights Act. In particular, we find that the size of the black population required to get over the “hurdle” of no representation went down. In other words, covered cities with average black populations had a better chance of gaining representation. Moreover, few uncovered cities have moved beyond electing a single black city councilor, suggesting the VRA was also instrumental in moving American cities beyond a single token minority representative to true political incorporation and decision-making.

Together, these findings suggest that we have made remarkable strides towards representational equality thanks to the Voting Rights Act, and that voting protections for minorities are still important. While many of the earlier tactics of disenfranchisement and dilution no longer work, minority voters continue to face significant obstacles at the voting booth. Earlier this year, the day after Supreme Court effectively struck down the “heart of the Voting Rights Act of 1965” by a 5-to-4 vote, dismantling the Section 4 provision that required states (mostly in the South) to obtain federal clearance to change their election laws, Texas immediately adopted a voter ID law that many saw as targeting minority voters. The US Department of Justice is currently suing North Carolina for what it sees as tough new laws that impose restrictions on minority voters. Florida is once more looking to ask minorities to prove citizenship before they are allowed to vote. These are but the earliest examples of how loss of Section 4 may impact minority rights, and further evidence that we are far from achieving all the promises of the Voting Rights Act.

This article is based on ‘Are We There Yet? The Voting Rights Act and Black Representation on City Councils, 1981–2006’ in the October edition of The Journal of Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/19E2EMV

_________________________________________

Paru Shah – University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Paru Shah – University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Paru Shah is an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Her research centers on American politics, with an emphasis on race, ethnicity and politics, urban politics, and public policy analysis.

_

Melissa Marschall – Rice University

Melissa Marschall – Rice University

Melissa Marschall is the Albert Thomas Associate Professor at Rice University, Houston, Texas. Her research focuses on immigrant and minority incorporation, education policy, race and representation, and political behavior.

_

Anirudh Ruhil – Ohio University

Anirudh Ruhil – Ohio University

Anirudh Ruhil is an Associate Professor at Ohio University and the Associate Director of Research and Graduate Programs. He has published widely on issues of race and representation in local America, state politics and policy and education policy.