With immense pressure on public finances during the Great Recession restricting the use of fiscal policies, many governments have turned to monetary policy instruments to aid economic recovery. But how effective are these policies in times of recession? Silvana Tenreyro and Gregory Thwaites find that changes in official interest rates have no discernible effect on the economy during recessions. In light of this, they argue that recent signs of economic recovery are there in spite of the current policy mix, not because of it.

With immense pressure on public finances during the Great Recession restricting the use of fiscal policies, many governments have turned to monetary policy instruments to aid economic recovery. But how effective are these policies in times of recession? Silvana Tenreyro and Gregory Thwaites find that changes in official interest rates have no discernible effect on the economy during recessions. In light of this, they argue that recent signs of economic recovery are there in spite of the current policy mix, not because of it.

Much of the industrialised world has been trying to cut public borrowing without impeding recovery from the Great Recession. Central banks have attempted to square this circle by loosening monetary policy. For example, in 2012, the UK finance minister George Osborne stated that ‘[T]heory and evidence suggest that tight fiscal policy and loose monetary policy is the right macroeconomic mix’ for countries with excessive private and public debt.

A number of recent studies have found that fiscal policy is particularly powerful in recessions – tax rises and spending cuts harm growth more when the economy is already weak. But if monetary policy is still effective, these big negative effects could in principle be offset by lower interest rates. We find that, at least in the US, this is not the case: official interest rates have no discernible effect on the economy during recessions. So a crucial ingredient– the ability to stimulate a recession-hit economy by cutting policy rates – may be missing from the prevailing policy mix.

Auerbach and Gorodnichenko estimate the impact of tax and spending shocks on the economy, and how the impact varies over the economic cycle, using a ‘smooth transition local projection model’. They find that fiscal policy is more powerful in bad times than in good. We use the same framework to test whether the impact of shocks to the Federal Funds rate, identified by Romer and Romer, similarly varies over the cycle. A local projection model essentially involves regressing the response variable on a shock lagged a certain number of periods. The regression coefficient on the shock is the level of the impulse response at that horizon. Estimating a family of these regressions with varying lags, one can trace out a normal impulse response function.

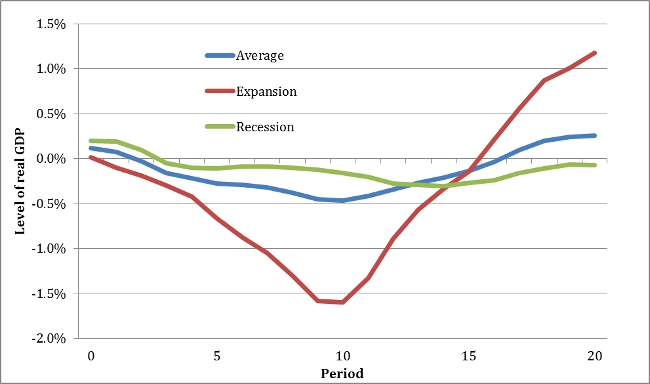

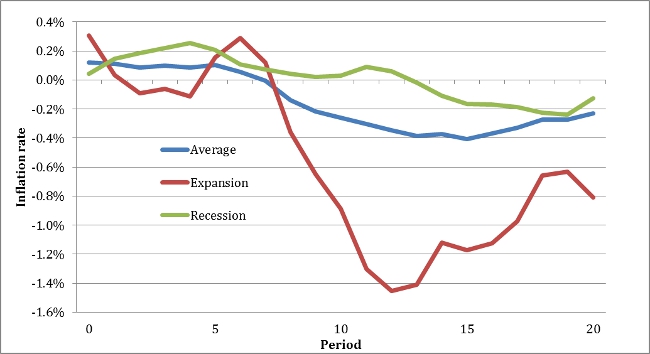

The average impulse response functions of the levels of real GDP and the quarterly annualized inflation rate to a 1 percentage point rise in the Fed Funds rate are shown as the blue lines in Figures 1 and 2. We find that unexpected changes in interest rates have the textbook effects on the US economy on average – a rise in interest rates first reduces spending, especially on durable goods, and then inflation.

Figure 1 – Level of real GDP given 1 percent rise in Federal Funds Rate

Figure 2 – Quarterly annualised inflation rate of GDP deflator given 1 percent rise in Federal Funds Rate

The ‘smooth transition’ part comes in when allowing the impact of monetary policy to vary over the cycle. The method estimates two sets of coefficients. When the economy is expanding strongly and the economy is hit by a policy shock, the model gathers information about the ‘good times’ coefficients. When it is contracting, we get information about the ‘bad times’ coefficients. When the economy is at neither extreme, the data informs estimates of responses in both booms and recessions. Local projection methods are well-suited to studying how the impact of shocks varies over the cycle because the only thing that matters is the state of the economy when the shock hits. In contrast, standard methods, such as vector autoregressions (VARs), assume that the propagation of an old shock only depends on how the economy is doing later on.

The headline results are shown in Figures 1 and 2 – the red line is the impulse response in a boom, while the green line is the impact in a recession. The difference between these lines is statistically significant at standard levels, suggesting that the differences we see are not just there by chance.

What could be driving these results? We do not find any evidence that fiscal policy is tending to counteract monetary policy more in recessions. Nor do we find the responses of credit spreads or quantities magnifying policy shocks by more in booms. In line with another recent paper, we do find that policy tightenings are more powerful than loosenings. This provides another reason to doubt the efficacy of a ‘tight fiscal, loose monetary’ policy mix in current conditions. But it does not explain our results, because the past incidence of unanticipated increases in the policy rate is no higher in booms than in recessions.

So, having ruled out a number of plausible candidates, we are left with a puzzle as to the underlying economic reasons for our findings. If our findings are correct, recent signs of economic recovery are there in spite of the current policy mix, not because of it. And if the world economy slips back into recession, we cannot rely on conventional monetary policy to get us out.

This article is based on LSE CEP discussion Paper 1218 “Pushing on a string: US monetary policy is less powerful in recessions”.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1aoWscF

_________________________________

Silvana Tenreyro – LSE Department of Economics

Silvana Tenreyro – LSE Department of Economics

Silvana Tenreyro is Professor in Economics at the London School of Economics. She is Board Member of the Review of Economic Studies and serves as Associate Editor for the Journal of the European Economic Association, the Journal of Monetary Economics, the Economic Journal, and Economica. Tenreyro is an external MPC member for the Central Bank of Mauritius, Member at Large of the European Economic Association (EEA), Leading academic at the Centre for Macroeconomics, Research Associate at the CEP Macroeconomics program, and Research Affiliate at CEPR. In the past, she acted as Panel Member for Economic Policy, Director of the IGC Macroeconomics Programme, and she chaired the Women in Economics Committee of the EEA. Her main research interests are Macroeconomic Development and Monetary Policy. Recent publications include “Technological Diversification” (AER), “The Timing of Monetary Policy Shocks” (AER), and “Volatility and Development” (QJE).

Gregory Thwaites

Gregory Thwaites is a PhD student at the LSE.