Even since before the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008, the growing level of poverty in America has been of great concern to government and policymakers. David Brady argues that while most research into the causes of poverty focusses on joblessness, the majority of poor people in the U.S. are working poor. By examining working poverty in the past two decades, he finds that the decline in unionization is closely linked to the rise in poverty. He writes that unions are a pathway to increased economic security for workers, through higher wages and benefits, increased job security and the greater regulation of risks.

Even since before the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008, the growing level of poverty in America has been of great concern to government and policymakers. David Brady argues that while most research into the causes of poverty focusses on joblessness, the majority of poor people in the U.S. are working poor. By examining working poverty in the past two decades, he finds that the decline in unionization is closely linked to the rise in poverty. He writes that unions are a pathway to increased economic security for workers, through higher wages and benefits, increased job security and the greater regulation of risks.

When Americans think about poverty, they think of joblessness. The widely held perception is that the typical poor person is unemployed, and lacks employment opportunities, human capital or the will to work. This widely held perception is also prominent in scholarly research. A great deal has been written by sociologists about joblessness, jobless young men, jobless single mothers, and the consequences of joblessness for families and health. Indeed, William Julius Wilson’s classic When Work Disappears was motivated by the plight of jobless neighborhoods. Economists, for their part, also focus great attention on unemployment rates and the business cycle. Purportedly, the most important thing is to get the economy to provide more jobs and raise the demand for workers so that more of the poor will be pulled into gainful employment.

The problem with this perception is that most poor people in the U.S. are working poor. Far more people reside in households with employed members than reside in unemployed households. In the past few decades, about three-quarters of American working-age poor households contained an employed worker. When one thinks about the basic math, this actually isn’t surprising. Imagine 10 percent of working age households are unemployed. This would be an unusually high rate of unemployment for the U.S, and in reality, many unemployed households escape poverty because they receive unemployment or disability insurance that is tied to past employment and/or have other sources of income. Still, presume 10 percent of working age households are unemployed and thus 90 percent are employed. For there to be more unemployed poverty than working poverty, almost all of the unemployed households would have to be poor and almost none of the employed households could be poor. To be concrete, imagine 80 percent of unemployed households are poor. If poverty among employed households even exceeds 9 percent, there would be more working than jobless poor. Because the U.S. always contains dramatically more people in employed households than unemployed households, there is always more working than jobless poverty.

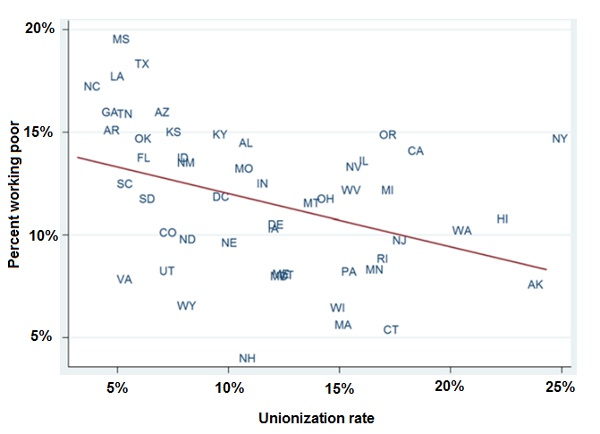

Motivated by these facts and the unfortunate lack of research on working poverty in the U.S., Regina Baker, Ryan Finnigan and I have examined the problem from 1991 to 2010. We found that that unionization is a major driving force behind the problem of working poverty; where unions are weak, working poverty is widespread and where unions are stable, working poverty is much less common. Moreover, the striking decline of unionization in the U.S. has stalled what might have been progress in reducing working poverty. We have tried to understand why working poverty has remained so stubbornly high throughout the ups and downs of the business cycle and despite undeniable long term economic development, and have looked closely at the differences in working poverty across the U.S. states and over time, as shown in Figure 1, below. In states like Mississippi and Texas, almost one-fifth of people in employed households are poor. In states like New Hampshire, less than 5 percent of people in employed households are poor.

Figure 1 – Working Poverty Rate and Unionization across 50 States and the District of Columbia

Note: Unionization rate is percent of civilian wage and salary employees, aged 16 years and older who are members of labor unions, measured in the same year

States differ in a number of ways that could explain the vast differences in working poverty. However, state-level unemployment and economic growth cannot explain much of the variation in working poverty. Also, social policies that differ across states – such as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families benefit levels – are only a small part of the story. Beyond state-level economies and policies, it could be simply the composition of states that explains the differences in working poverty. Indeed, Mississippi and Texas have far more less educated people and more single mother households than states like New Hampshire. We used a technique called multi-level models to incorporate information on the individual characteristics of individuals along with information about the states in which they reside. Of course, individual characteristics do matter – those with college degrees and two-earner married couples are much less likely to be poor. But, concentrating on such individual characteristics neglects the important factor of unionization that we highlight.

Unionization has larger effects on working poverty than the economic performance or social policies of the state in which one resides, as well as many other well-studied individual predictors of poverty. For example, if the average level of unionization in states 1991-2010 (13.5 percent) rose to the maximum in our sample (New York in 1991), the odds of working poverty would decline by about 1.8. This is effect is comparable to the effect of residing in a single mother household.

Why does unionization matter so much to working poverty? Unions raise wages and benefits, and regulate risks by enforcing safety regulations and increasing job security. Unions also protect and encourage the creation of better jobs. Also relevant, unions facilitate policies that help working families and cultivate norms of equality. Unions reduce the likelihood of poverty-inducing events like downward job mobility, pay cuts and injuries. Furthermore, unions mitigate the consequences when such events occur by elevating the pay of other household members and by insuring against loss through the cumulative advantages of better pay before such events. All of these pathways between unions and economic security are fundamental to reducing working poverty.

Encouragingly, unions do not discourage employment. Though it is often alleged that unions prevent job growth and/or exclude certain kinds of workers, we find no evidence for such claims. Further, unions do not reduce working poverty because they influence the selection into employment. Unions also seem to reduce working poverty among all kinds of workers, in different industries and occupations, and among women, men, and racial/ethnic minorities.

Unions have declined dramatically in the U.S. In the early 1990s, fully 15 percent of American workers were unionized. But, by 2010, this rate had fallen to 11 percent. In the early 1990s, more than 25 percent of workers in states like New York, Hawaii and California were unionized – a level much higher than present day Germany. By 2010, very few states had unionization rates above 20 percent and most were still falling. If one looks further back to the 1980s or 1970s, the decline of unionization is even more pronounced. This dramatic decline of unionization is really one of the most important threats to American workers and the economic security of American households. Moreover, the decline of unions is a crucial influence on poverty. To better understand poverty in the U.S., scholars and the public need to pay more attention to working poverty and to the decline of unions.

This article is based on the paper, “When Unionization Disappears,” in the October 2013 issue of the American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/16J0jAn

_________________________________

About the author

David Brady – WZB

David Brady – WZB

David Brady is Director of the Inequality and Social Policy Research Unit at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). His main fields of interest are poverty and inequality, in particular their causes, measurement and consequences. His book Rich Democracies, Poor People: How Politics Explain Poverty (Oxford University Press, 2009) analyzes how politics explain why poverty is so much higher in the US than in other affluent democracies.

4 Comments