With the approach of the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, James D. Boys reflects back on JFK’s unfinished presidency. He notes that Kennedy is often judged on his promise, rather than his substantial achievements in office, and imagines a second Kennedy administration, speculating that without the emotion created by Kennedy’s death, the Civil Rights Act would not have passed Congress.

With the approach of the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, James D. Boys reflects back on JFK’s unfinished presidency. He notes that Kennedy is often judged on his promise, rather than his substantial achievements in office, and imagines a second Kennedy administration, speculating that without the emotion created by Kennedy’s death, the Civil Rights Act would not have passed Congress.

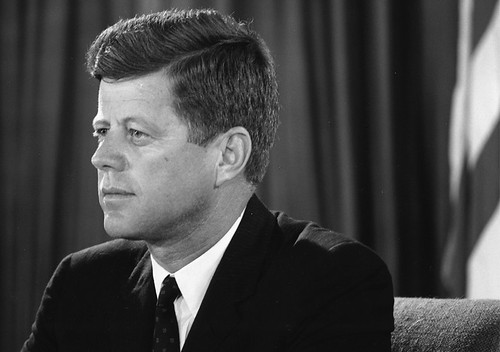

50 years after his assassination in Dallas, Texas, President John F. Kennedy continues to rank as one of the most popular chief executives in American history. He was, of course, only in office for a little over a thousand days, leading to obvious questions as to the rationale for his high standing, especially considering that most Americans alive today have no living memory of his administration.

Perhaps more than any other president, JFK is judged to a great extent on his promise, as opposed to his specific achievements in office. However, this is a situation that risks undermining the feeling of euphoria that he brought to the presidency as well as his great achievements in office; of saving the world during the Cuban Missile Crisis and his work in securing the first nuclear test ban treaty, signed shortly before his fatal trip to Texas. Kennedy set the tone for an idealised, romanticised presidency that many, if not all, of his successors have sought to emulate and against which, all have come up short.

Indeed, the fact that both Republicans and Democrats have sought to emulate or bask in Kennedy’s reflected glory speaks to the importance of his presidency. He redefined the office in terms of public relations, style and image. Alas, his imitators have all too often failed to see the substance behind the smile. He prevented Armageddon over Cuba, repeatedly refused to commit ground troops to Vietnam, initiated the Apollo mission to the moon, signed a nuclear test ban treaty with the UK and the USSR, committed the United States’ government to the passing of civil rights legislation, created the Peace Corps and committed to a phased withdrawal of all US personnel from Vietnam by 1965, with the first 1,000 advisers due home by Christmas 1963. During his 1,000 days in office, John F. Kennedy redefined the office of the presidency in terms of its ability to motivate and inspire a nation and, to a great extent, the world.

Having grown substantially in office, Kennedy was not taking re-election for granted. His trip to Texas marked the beginning of an anticipated year-long campaign to secure a second term. The great unknown element is what would Kennedy have addressed between 1964 and January 1969 and how would this differ from what occurred under Lyndon Johnson? Historians and commentators routinely suggest that either little would differ (as LBJ retained Kennedy’s cabinet), or else that Kennedy’s living presence would have resulted in a far more equitable and peaceful world.

The truth, however, would certainly have been somewhere in-between. Having repeatedly refused to commit ground troops to Southeast Asia during his first term, Kennedy would have continued his efforts to ensure that the Vietnam withdrawal, commenced in the fall of 1963, was completed on schedule. While this would naturally have a great benefit for those Americans not impacted by the draft, (particularly African Americans), there would likely be a major downside to a second Kennedy Administration. Having won re-election JFK would have struggled to pass the planned Civil Rights legislation due to vehement opposition, not only from Republicans, but primarily from Southern Democrats.

Lyndon Johnson’s ability to pass the 1964 and 1965 bills was due in large part, to his willingness to exploit the assassination as an emotional rationale to manipulate members of Congress. Even so, this was achieved at the loss of the Democratic grip on the southern states, which in 2013, continue to be dominated by Republicans. Kennedy, without LBJ’s mastery of Congress and without the emotional leverage caused by his own demise, almost certainly would have failed to pass the legislation that he had introduced. This would have had major implications for African Americans and ensured that the Republican Solid south that emerged in 1968 would not have materialised, with implications for future presidential elections.

Further afield, a planned state visit to Moscow may have helped keep Nikita Khrushchev in power and enable Kennedy and Khrushchev to develop their relationship that had begun to improve after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Having signed the test ban treaty, the two men could easily have implemented the vital lessons that they had learnt from the Cuban crisis.

Counter-factual history has its detractors, but it is fascinating tool with which to consider a 1960s dominated by an 8 year term for JFK, devoid of the turmoil of Vietnam, but without the leap forward in civil rights that was only achieved in the aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/19yCVG2

_________________________________

Jam es D. Boys – Richmond University and King’s College, London

es D. Boys – Richmond University and King’s College, London

Dr. James D. Boys is a political historian specializing in the United States and its place in the world. He has a special interest in the study of the United States’ presidency and specifically in the administration of Bill Clinton. The Clinton administration’s formulation of foreign policy in the 1990s is the subject of James’ forthcoming book, Clinton’s Grand Strategy: US Foreign Policy in a Post-Cold War World (Bloomsbury, 2014). He is an Associate Professor of International Political Studies at Richmond University (London) and a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at King’s College, London. He maintains a website (www.jamesdboys.com) and tweets: @jamesdboys

Not sure you can say Kennedy prevented Armageddon, since the risk of a nuclear conflict only arose when he imposed a blockade, surely? Some would say that he brought the missiles to Cuba in the first place by his sponsoring of the attempted invasion of Cuba in the Bay of Pigs. And the Kennedy boys continued to plot against Castro even after October 1962. He would have stayed out of Vietnam, I guess. Having been beaten up by Khrushchev at a summit, and then gone head to head in Cuba, and having to worry about Berling as well – would he really want another confrontation with USSR? And would he want another Bay of Pigs, in a country thousands of miles away where the battle would be joined with a substantial, experienced guerilla army?