The so-called “nuclear option” to limit the filibuster was talked about for years before Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid finally moved forward with it last week. Michele Swers describes this move as the culmination of years of increasing polarization in the Senate. She goes on to argue that the elimination of the filibuster will only make bipartisan deals more difficult to attain and will ultimately shift power away from the legislative branch and into the executive.

The so-called “nuclear option” to limit the filibuster was talked about for years before Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid finally moved forward with it last week. Michele Swers describes this move as the culmination of years of increasing polarization in the Senate. She goes on to argue that the elimination of the filibuster will only make bipartisan deals more difficult to attain and will ultimately shift power away from the legislative branch and into the executive.

The Nuclear Senate

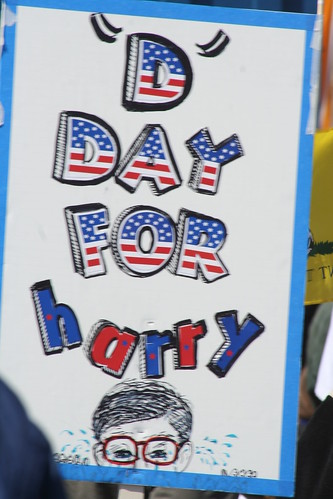

Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) and the Senate Democrats pushed the nuclear button this week and eliminated filibusters, but only on executive and judicial nominations (except for Supreme Court nominees). Why did they do it and what does it mean for the future of the Senate?

Why They Did It

The rules of the Senate are designed to elevate the rights of the individual in order to force the majority to accommodate the views of the minority. Unlike House members, senators can place holds on legislation and nominations, offer non-germane amendments on the floor, and yes, filibuster. With rights come responsibilities and in order for the Senate to function and pass legislation, senators must limit their use of these tools. As the parties have become more polarized with the Democrats becoming more uniformly liberal and the Republicans more conservative, each side views the other party’s policies as disastrous for the future of the country. Therefore, they are more willing to do whatever it takes, meaning deploy their procedural prerogatives, to prevent the other side from achieving a policy victory. The justification of the recent government shutdown as an effort to defund President Obama’s healthcare plan illustrates the point.

Additionally, in recent years, partisan control of the Senate has changed multiple times. When a majority party becomes the new minority, they remember how the opposition party abused the filibuster and fight even harder as a result. For example, when George W. Bush was President, Democrats took the unprecedented step of filibustering ten of his appellate nominees. Republicans resented these filibusters and their impact on President Bush’s efforts to fill judicial vacancies, thus they increased use of the filibuster when President Obama took office. Figure 1 below from The Century Foundation illustrates this dynamic. As the Senate has grown more polarized, the use of the filibuster (denoted by the number of motions filed to invoke cloture) has risen astronomically. The use of the filibuster increased with each change in party control of the Senate with the Republicans taking it to new heights in the Obama years.

Figure 1

The fight over judicial nominations brought the current conflict to a head. Republicans did not object to anything in the record of the three D.C. Circuit nominees. Instead they asserted that these vacancies do not need to be filled, citing the court’s caseload. Republicans also did not want more Democratic judges appointed to the court that rules on disputes involving the actions of federal agencies as Democratic nominees would be more sympathetic to Obama administration policies from health care to climate change.

While the Senate had reached deals to avert the nuclear option as recently as January and July of this year, this time was different. Unlike July when Senate Democrats agreed to withdraw certain nominees to get others confirmed, there were no nominees to trade. Moreover, most of the dealmakers who made up the Gang of 14 that averted deployment of the nuclear option over judicial nominees during the Bush years are gone from the Senate. Furthermore, the political calculus has changed for the Democrats. With President Obama and Democrats’ poll numbers dragged down by the problems with the Obamacare rollout and the continuing stalemate between the Republican-controlled House and Democrats, there is little chance that any of President Obama’s legislative initiatives will be passed. Therefore, Democrats do not need to preserve comity in the hopes of gaining immigration reform, gun control, or a grand bargain over the budget. Moreover, if Obamacare continues to falter, the Democrats could lose their majority in the 2014 elections. Therefore, they are looking to the nomination process to secure the President’s legacy through the actions of administrative agencies and the rulings of the courts.

What Does the Deployment of the Nuclear Option Mean for the Future of the Senate?

In the near term, deployment of the nuclear option means we will see Obama nominees confirmed to the DC Circuit, the Federal Housing Administration, and the Federal Reserve. However, it also poisons the well and makes bipartisan deal making that much harder for those who are engaged in it, such as House and Senate Budget Chairs Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Patty Murray (D-WA) and the conference they are leading to try to reach a budget agreement.

In the long term, eliminating the filibuster on judicial and executive nominees makes it easier for majorities to achieve their policy priorities without having to consult or rely on the votes of the minority. Since the button has already been pressed, when party control switches again, the new Republican majority could decide it needs to eliminate the filibuster on Supreme Court nominees or on certain kinds of legislation such as Appropriations bills. Perhaps a Republican Congress and a Republican president will decide that the need to reduce dependence on foreign oil is so severe that the filibuster should not be used to block oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve.

Finally, the elimination of the filibuster marks a further shift of power away from the legislative branch to the executive branch and the courts. With the potential threat of a filibuster, a president must anticipate the reaction of the minority party when considering whom to appoint to a position. Presidents are forced to moderate their picks to select someone that can attract the support of a broad coalition. Without the filibuster a President George W. Bush and a Republican controlled Senate could have appointed even more of the strongly conservative judges that Democrats decried as out of the mainstream. Thus when Republicans control both the presidency and the Senate, we should expect future Republican judicial nominees to look more like Robert Bork, the Reagan Supreme Court nominee who Democrats defeated based on his ideological views, and less like Anthony Kennedy, another Reagan nominee and current swing vote on the Supreme Court. The increasing polarization of the Senate will lead to increasing polarization of the courts for nominees who are selected in periods when the same party controls the Senate and the presidency.

Furthermore, the partisan dysfunction that grips Congress continues to limit members’ ability to pass legislation to deal with the country’s problems. As a result, President Obama and future presidents will increasingly use their administrative authority to address policy problems. Thus, after a Democratic controlled House and Senate failed to pass a climate change bill, President Obama turned to the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to pursue policies to curb greenhouse gas emissions. The DC Circuit, which will include new nominees more friendly to the President’s agenda, will now rule on whether, for example, the EPA has the authority to limit carbon emissions from power plants. Thus, partisan dysfunction forces presidents to utilize their executive authority rather than seeking legislation to resolve policy problems. These administrative actions will be challenged in a court whose newest appointees will likely have preferences that are more aligned with the president than they would if he had to make his appointments with an eye to avoiding a filibuster threat.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/IccOyB

_________________________________

Michele Swers – Georgetown University

Michele Swers – Georgetown University

Michele Swers is an Associate Professor of American Government in the Department of Government at Georgetown University. Her research interests encompass Congress, Congressional elections, and Women and Politics. Her most recent book, Women in the Club: Gender and Policy Making in the Senate (University of Chicago Press 2013) examines the impact of gender on senators’ policy activities in the areas of women’s issues, national security, and judicial nominations.