Among the demographic changes experienced by the United States over the past decades, perhaps the most significant are the growth of single-person (solo) households and the decline of married-couple households. These changes have serious implications for policy makers, planners, and public service providers. In a recent study, Devajyoti Deka identified some of these implications by comparing the living, moving, and travel characteristics of persons from American solo households with adults from married-couple households.

Among the demographic changes experienced by the United States over the past decades, perhaps the most significant are the growth of single-person (solo) households and the decline of married-couple households. These changes have serious implications for policy makers, planners, and public service providers. In a recent study, Devajyoti Deka identified some of these implications by comparing the living, moving, and travel characteristics of persons from American solo households with adults from married-couple households.

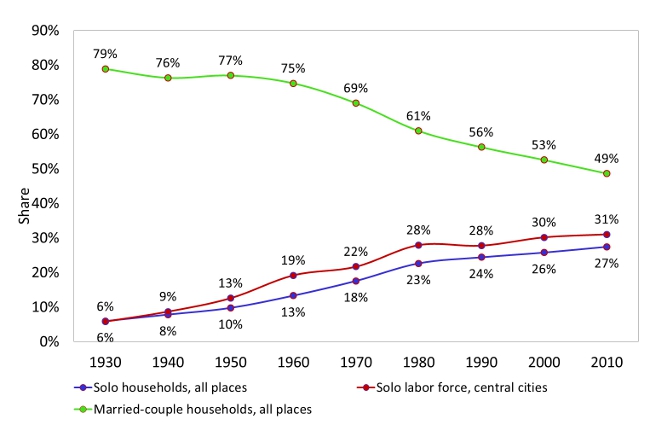

Between 1930 and 2010, the proportion of married-couple households decreased from almost 80% to less than 50%, whereas the proportion of solo households increased from a little over 5% to almost 30%. This transformation in living arrangements has been attributed by researchers to many factors, including higher education and labor force participation of women, adoption of ‘no-fault’ divorce laws by states, cultural acceptance of solo households by society, and an increasing life expectancy resulting in a growing number of elderly single persons.

Solo workers have historically preferred to live in cities instead of suburbs because of an earnings advantage. While workers from married-couple households earn fairly similar amounts by living in cities as in suburbs, solo workers earn more by living in cities. As shown in the figure 1, the share of solo central-city labor force has been higher than the share of solo households in all places since 1940. Thus, continued growth of working-age solo persons can potentially contribute to the revival of American central cities. One advantage of solo workers is that they can migrate to other places more easily than adults from married-couple households because they do not have to worry about spouses’ jobs or children’s schooling. Their ability to move helps the overall labor market because employers can attract employees from distant places.

Figure 1: Solo Household Share of Central-City Labor Force

The increase of working-age solo persons can be considered a blessing for American cities because they lost large volumes of workers and households for several decades. Working-age solo persons are beneficial to cities for several reasons. They prefer residential locations where activities are within walking distance and public transport is readily available. They are more likely to live in apartments than single-family homes. They are less likely to own cars and more likely to live close to work. If all persons had the living and transportation preferences of solo workers, more people would live in cities and take public transportation or walk to places. The dependence on the automobile would decrease and perhaps the air people breath would be a little cleaner.

There is little evidence to suggest that the increase of working-age solo persons in cities is due to deliberate strategies adopted by American cities. Given their small scale, urban revitalization efforts cannot account for the prolonged and significant growth of solo workers in cities. It so happened that the share of solo female workers was always high in central cities because of their propensity to take jobs that were typically located in urban areas. Their propensity to make short commutes made them live close to their work. The share of male workers in cities also started increasing in recent decades as a result of transformations in the labor market and growing acceptance of solo households.

While solo workers in cities earn more than similar workers in other areas, they also have to pay more to live there. In the first place, solo workers do not get the benefit of sharing housing space, utilities, etc., with other household members. Second, housing space is more expensive in cities than suburbs, although housing units are sometimes more expensive in suburbs because of larger size. For working-age solos to continue to be attracted to cities and contribute to city economies, city governments will have to recognize them as a significant population group and pay attention to their employment, housing, and transport needs.

Although the growth of solo households may be exciting for a number of reasons, its long-term consequences are yet to be fully understood. Their growth, and the decline of married-couple households, can potentially mean a greater need for social support to individuals in the future. Individuals typically solve their problems by themselves or with support from family, friends, and society. The growth of solo households and the decline of married-couple households could essentially mean a decline in the role of family, and thus increased demands from the self, friends, and society. Unless the individual becomes more able or friends become friendlier, the burden of assistance will probably shift to society. There will be increased demand for public services and society at large will have to pay.

To comprehend how the burden on society might increase with the aging of today’s solo workers, consider the case of transportation. Today’s elderly persons are several times more likely to take a ride from a family member than to make a trip by public transportation. Since these rides are predominantly given by one spouse to another, society has to begin wondering who will give rides to today’s solo workers when they get old. While there is little doubt that they will require more public transportation service than today’s elderly persons in the absence of family support, providing service to them in cities may be less expensive than providing service to today’s elderly persons aging in suburban or exurban areas. However, in order for them to be able to live in cities, cities must make efforts to keep housing and transportation costs affordable for the elderly. For the continued growth of solo workers, cities will have to attract better jobs because higher demand may increase the cost of housing. These implications of the growth of solo households and the decline of married-couple households should make cities and public service providers aware of potential future challenges and prepare plans to meet those challenges.

This article is based on the paper “The Living, Moving and Travel Behaviour of the Growing American Solo: Implications for Cities,” which recently appeared in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/N2QppE

_________________________________

Devajyoti Deka– Rutgers University

Devajyoti Deka– Rutgers University

Devajyoti Deka is the Assistant Director of Research at the Alan M. Voorhees Center, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy in Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. He conducts research on social, economic, and environmental issues related to transportation.