Between 1992 and 2012, nearly 170 Southern state legislators switched from the Democratic to the Republican Party. While many would assume that these conversions came about as legislators became increasingly concerned about their re-election chances, new research from Antoine Yoshinaka points to another explanation. He finds that shifts in the longer term characteristics of constituencies; such as changes to the black and Latino populations, as well as the state’s larger political context, explain why many legislators switch parties and others do not.

Between 1992 and 2012, nearly 170 Southern state legislators switched from the Democratic to the Republican Party. While many would assume that these conversions came about as legislators became increasingly concerned about their re-election chances, new research from Antoine Yoshinaka points to another explanation. He finds that shifts in the longer term characteristics of constituencies; such as changes to the black and Latino populations, as well as the state’s larger political context, explain why many legislators switch parties and others do not.

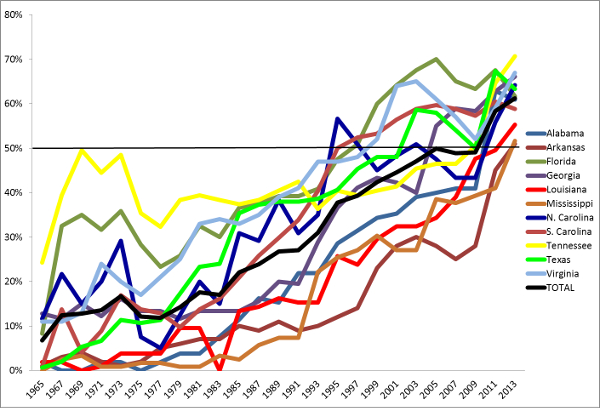

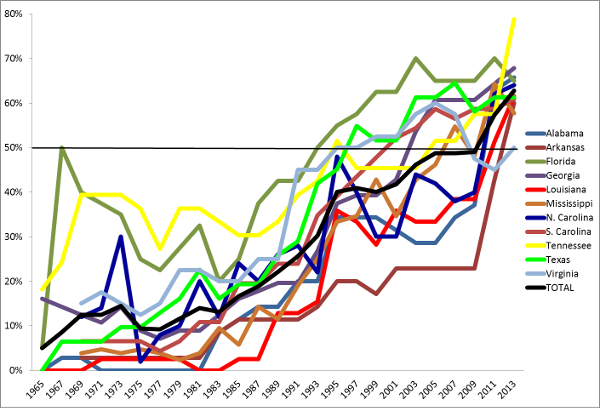

One of the most significant transformations of the American political landscape over the last several decades has been the realignment of the American South from a one-party Democratic stronghold to a Republican-dominated region. While this shift at the national level (the U.S. House and Senate) started about half a century ago, it is only in recent decades that Republicans started making significant inroads at the state and local level. In 1990 Democrats controlled all 22 state legislative chambers in the South; after the 2012 elections all but one were in the hands of the GOP. Figures 1 and 2 show how the Republicans’ hold on state houses and state senates in the South accelerated quickly in the 1990s and 2000s.

Figure 1 – Percentage of Republican state house seats in the U.S. South, 1965-2013

Figure 2 – Percentage of Republican state senate seats in the U.S. South, 1965-2013

An important factor fueling this change has been the conversion of Democratic elected officials to the Republican Party. Between 1992 and 2012, nearly 170 Democratic state lawmakers switched to the GOP. Recently, my co-author and I began to unpack this phenomenon in a systematic fashion. And what we found might surprise some: short-term electoral competition doesn’t appear to exert much influence on the decision to switch parties. Rather, the characteristics of the constituency as well as the larger political context in the state seem to explain why some legislators switch parties while others do not.

At the national level, cases of party switching have received heavy media scrutiny. In 2001, Vermont Senator Jim Jeffords left the Republican Party and gave the Democrats the majority in the Senate; in 2009 it was Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter’s turn to bolt the GOP. At the state level, party switchers handed Republicans a legislative majority in several states, and the U.S. South has been a fertile ground for party switching. States outside the South such as Maine and Pennsylvania have also seen a fair number of party switchers including some that flipped majority control of a legislative chamber. Yet, until recently political scientists knew very little about the factors that systematically induce party switching at the state level. In recent research, my co-author Seth McKee and I estimate a series of multivariate regression models that allow us to test various hypotheses regarding the factors that correlate with party switching.

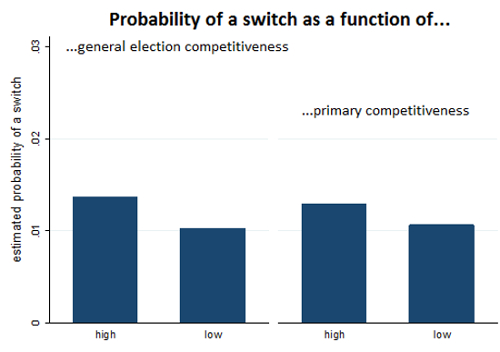

One theory is that legislators in danger of losing their reelection are prone to switch parties. However, this is not borne out by the data. Looking at the most recent completed decade of data (2002-2012) in the U.S. South, Figure 3 shows that the probability that a Democratic state legislator switches party isn’t related to either his primary margin at the last election or his general election vote shares. Since competitiveness in the previous election is generally one of the strongest predictors of competitiveness in the upcoming election, we must look elsewhere for a systematic explanation.

Figure 3 – Party switching and electoral competitiveness

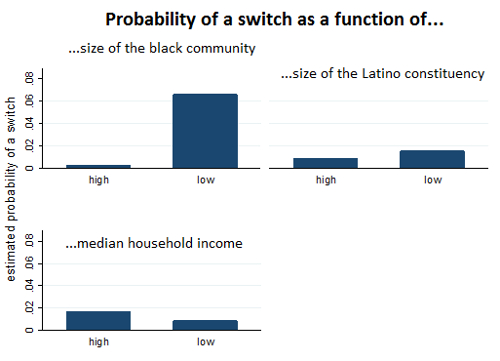

What we found was that the characteristics of the constituency, which have longer-term implications, correlate highly with party switching. Figure 4 shows that a Democratic lawmaker representing a constituency with a small number of African-American constituents is much more likely to switch parties than a Democrat in an area with a large number of black constituents. A similar (albeit less striking) pattern can be found with respect to the size of the Latino constituencies. Moreover Democratic politicians elected in wealthy districts are more likely to jump to the GOP. While some of these differences may appear small, we must remember that switching parties is a rare event. Still, going from, say, 0.01 to 0.02 means that the probability has doubled, which is quite significant when aggregated over the hundreds of Democratic lawmakers serving in office.

Figure 4 – Party switching and constituency characteristics

In concert with our non-finding pertaining to electoral marginality, we interpret these results as indicative of lawmakers responding to longer-term trends in their constituencies rather than to immediate electoral pressure. To be sure, the two are intertwined, yet they are distinct from one another: a competitive environment does not automatically yield a competitive election. Even in this era of Republican dominance in the South, Democratic incumbents at the state and local level are often quite secure in their reelection, at least in the near-term. An incumbent, even a Democratic one, usually wins reelection in the South. So party switching isn’t so much a response to an immediate threat of removal by the voters. This is consistent with another finding that Democrats who switch to the Republican Party often run for higher elective office soon thereafter. Ambition, then, is a potent force behind the decision to switch parties.

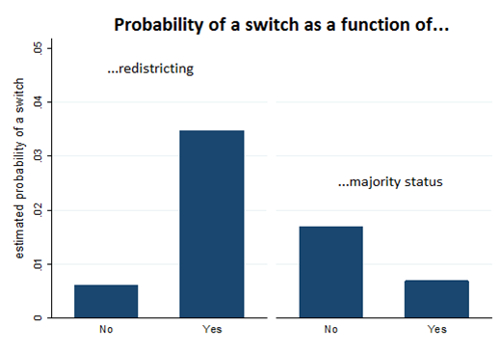

Finally, the larger political context highly correlates with the propensity to switch parties. Figure 5 shows that party switching is much more likely to occur concurrently with the redrawing of district boundaries and that minority-party legislators are more likely to switch parties than lawmakers belonging to the majority. These results suggest that factors outside the direct control of individual lawmakers, which create new opportunities, can explain party switching.

Figure 5 – Party switching and statewide context

Perhaps the most well-known party switcher of all, Sir Winston Churchill (who switched parties twice) once quipped that “anyone can rat, but it takes a certain amount of ingenuity to re-rat.” Like southern Democrats who switch before running for another office, switching parties certainly helped fulfill some of Churchill’s ambitions. He did, after all, become Chancellor of the Exchequer after re-joining the Conservative Party in 1924, and of course he became Prime Minister a decade and a half later. Being rewarded with a plum position is also common in the United States. Yet, party switching on the whole remains a relatively rare event. This is because it is costly to switch parties. Voters do not always welcome such behavior on the part of their elected officials. Some view it as a breach of trust; switching may be branded as crass or opportunistic. These costs help explain why most lawmakers – even those ideologically at odds with their party – never jump ship. After all, no one wishes to be compared to a rat.

This article is based on the paper Late to the parade: Party switchers in contemporary US southern legislatures in Party Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/NHIiit

_________________________________

Antoine Yoshinaka – American University

Antoine Yoshinaka – American University

Antoine Yoshinaka is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Government at American University, Washington DC. His research examines how institutions and the preferences of political actors influence political outcomes. Some of his recent work on congressional redistricting, for instance, examines the various ways in which partisan mapmakers strategically allocate uncertainty across districts.