Last week the Senate Intelligence Committee voted to declassify parts of its controversial report into the CIA’s practices in the aftermath of 9/11. Allison Stanger warns against interpreting this and the likely termination of the collection of telephone meta-data as the beginning of the end of the U.S. surveillance state. She argues that most of the emergency measures that quickly became business as usual during the Bush Administration are still on the books, and that these will still allow the government to track the communications of Americans abroad, as well as their Internet traffic that is not based in the U.S.

Last week the Senate Intelligence Committee voted to declassify parts of its controversial report into the CIA’s practices in the aftermath of 9/11. Allison Stanger warns against interpreting this and the likely termination of the collection of telephone meta-data as the beginning of the end of the U.S. surveillance state. She argues that most of the emergency measures that quickly became business as usual during the Bush Administration are still on the books, and that these will still allow the government to track the communications of Americans abroad, as well as their Internet traffic that is not based in the U.S.

The Senate Intelligence Committee voted on April 3 to declassify portions of its 6,300 page report on the CIA’s detention and interrogation practices during the George W. Bush administration. The report is said to expose “brutality that stands in stark contrast to our values as a nation,” according to a written statement from the Committee’s chairwoman, Senator Diane Feinstein, and to reveal that the CIA misled the public about the effectiveness of its extreme methods. Acknowledging the excesses of the previous administration, however praiseworthy, does little to address the larger reality: The Obama administration continues to support many practices put in place by its predecessors that effectively cordon off large segments of executive branch activity from public scrutiny.

It is hard to imagine President Obama not approving the report’s declassification. He has said he wants the findings of the report to be made public and as a candidate opposed the CIA’s enhanced interrogation tactics, which included depriving suspects of sleep for days at a time, slamming them against walls, and waterboarding them. The report is said to dispute the claim that these brutal methods produced any vital intelligence breakthroughs. That finding would coincide with the conclusions of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Board (an independent, bi-partisan agency within the executive branch), whose January 2014 report concluded,

“We have not identified a single instance involving a threat to the United States in which the telephone records program made a concrete difference in the outcome of a counterterrorism investigation. Moreover, we are aware of no instance in which the program directly contributed to the discovery of a previously unknown terrorist plot or the disruption of a terrorist attack.”

But what of the overwhelming majority of wartime emergency programs initiated after 9/11 that the Obama administration has allowed to continue, prompting Bush Press Secretary Ari Fleischer in 2013 to claim that Obama was “carrying out Bush’s 4th term”? Whatever one may think of the intelligence contractor turned leaker Edward Snowden, his revelations unveiled the vast surveillance state that 9/11 unleashed. Snowden’s documents, taken as whole, revealed no less than a complete transformation in NSA operating procedures after 9/11. Prior to that date, the NSA’s awesome power was explicitly not to be directed at US citizens. After President George W. Bush’s secret executive order of October 2001, NSA protocol flipped from targeted searches (search then seize) to dragnet searches (seize then search under approved conditions). What began as wartime emergency measures following an attack on American soil became the new normal. In President Obama’s words, “It is hard to overstate the transformation America’s intelligence community had to go through after 9/11.”

Congress’s 2001 Patriot Act and the 2008 amendments to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) then sanctioned the NSA’s permanent transformation as legitimate and legal. The Patriot Act lowered the barriers to legal surveillance by allowing the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to review requests to suspend privacy rights. The Surveillance Court only hears arguments from the Justice Department and not opposing views, and Chief Justice Roberts has unilateral power to select its members. The determination of whether or not an individual’s right to privacy should be upheld is made behind closed doors and beyond public scrutiny—until Snowden forced those choices into public view.

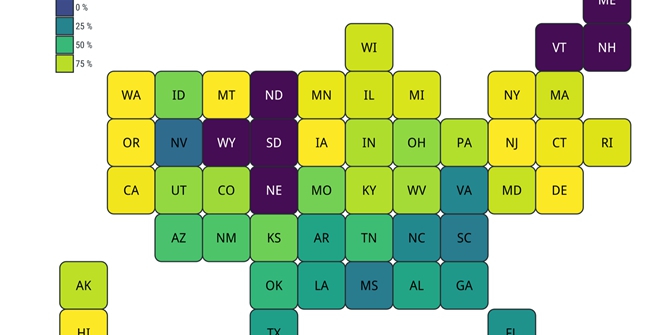

Section 215 of the Patriot Act authorized dragnet surveillance of the telephone records of American citizens, the collection of meta-data about which other numbers a person calls, for how long, and how frequently, not the actual contents of private conversations. That program is likely to end soon, as it has been criticized from all points of the political spectrum, and President Obama announced his intention to do so in his January 17 NSA speech. Federal judge Richard J. Leon of the District of Columbia has deemed NSA collection of American telephone records likely to be unconstitutional; “James Madison would be aghast,” he pronounced. Another federal judge, however, has deemed the practice in keeping with the Constitution, making Supreme Court consideration of the issue likely. Section 215 is up for renewal by Congress in June 2015, and it is hard to imagine, given the controversy the program has generated, that a majority of Congress would choose to associate itself with the program’s continuation.

While ending the telephone metadata program would be a step in the right direction away from the wartime emergency measures that have become America’s business as usual, it will hardly put a dent in the national security surveillance state. Section 702 of the 2008 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Amendments Act allows the government to track the Internet communications and phone calls of foreigners who are “reasonably believed to be located outside the United States” with permission from the secret FISA court. If Americans are at one end of the communication, their electronic utterances can be legitimately monitored. Since many Internet communications cannot be situated geographically and often pass through fiber-optics cables located outside the United States, Section 702 provides legal cover for expansive snooping. For example, the NSA obtained data from Google and Yahoo by tapping fiber-optics cables on British territory.

To date, the US government has assumed that American citizens would trust them not to abuse these privileges. Yet when such a vast zone of secrecy persists, and technology has outstripped our laws, that trust becomes misplaced. “Given the unique power of the state,” President Obama has himself warned, “it is not enough for leaders to say: Trust us. We won’t abuse the data we collect. For history has too many examples when that trust has been breached.” If the telephone dragnet surveillance program comes to an end as anticipated, the green light to monitor e-mail, social media, and phone calls will persist in programs sanctioned by 702. To quote the President himself again, “Our system of government is built on the premise that our liberty cannot depend on the good intentions of those in power. It depends on the law to constrain those in power.”

Former CIA and NSA director Michael Hayden recently accused chairwomen Feinstein of being too “emotional” in her condemnation of CIA enhanced interrogation practices, questioning the objectivity of the report she seeks to declassify. He meant it as a put-down. Yet despite the insistence of intelligence officials, no convincing evidence has been presented that torture produced results, and there is plenty of evidence to suggest that it did not. Perhaps a bit more emotion in response to the trampling of American values and human rights in the name of security is precisely what American democracy now needs to correct its own excesses.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1lHxj5g

_________________________________________

Allison Stanger – Middlebury College

Allison Stanger – Middlebury College

Allison Stanger is Leng Professor of International Politics and Economics at Middlebury College and the author of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Leaks: The Story of Whistleblowing in America (Yale, forthcoming) and One Nation Under Contract: The Outsourcing of American Power and the Future of Foreign Policy (Yale, 2009). She received her PhD in Political Science from Harvard University and is also an LSE alum (Diploma in Economics).