The past two decades have seen falling homicide rates in Chicago, previously dubbed the ‘murder capital’ of the U.S. This decline in homicides has generally coincided with a period of gentrification of Chicago, but are the two related? Chris M. Smith takes a close look at how gentrifiers, private investors, and local government have contributed to the process of gentrification, which has had mixed results on gang homicides. She argues that while individuals and investors reduce homicide rates through gentrification, when local authorities demolish public housing, they may actually be intensifying gang violence through forced relocation.

The past two decades have seen falling homicide rates in Chicago, previously dubbed the ‘murder capital’ of the U.S. This decline in homicides has generally coincided with a period of gentrification of Chicago, but are the two related? Chris M. Smith takes a close look at how gentrifiers, private investors, and local government have contributed to the process of gentrification, which has had mixed results on gang homicides. She argues that while individuals and investors reduce homicide rates through gentrification, when local authorities demolish public housing, they may actually be intensifying gang violence through forced relocation.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Chicago, like other U.S. cities, experienced both rapid gentrification and a remarkable decline in crime. Political officials and city planners have since bolstered gentrification policies with the vision of revitalizing urban blight, decreasing crime, and bringing much needed tax revenue to urban neighborhoods. City dwellers and visitors easily spot gentrification when the address of a shabby payday-lending counter becomes a shiny new pet-grooming spa, and urban residents feel gentrification when they notice that they never used to feel safe walking in a particular neighborhood. Though the results of gentrification are familiar and visible, the processes of gentrification are incredibly complex in which higher income households directly and indirectly displace lower income households changing the character and composition of a neighborhood.

Various actors participate in the processes of gentrification. First, there are the gentrifiers themselves often hipsters, artists, and young urban bohemians moving into cheap neighborhoods located near the central business district with old Victorian housing stock and empty warehouses. They in turn develop a thriving art and music scene that attracts a second wave of young urban professionals to the neighborhood who pay higher rents for brownstones and invest in property renovations.

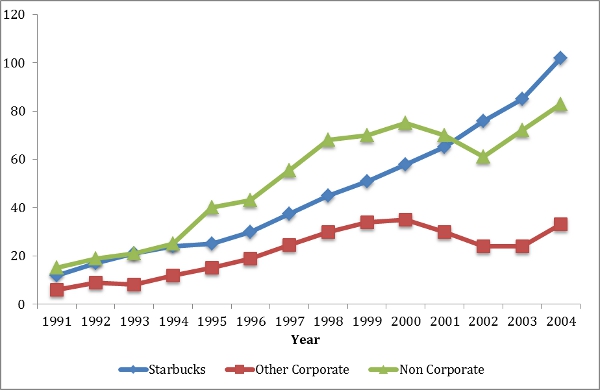

A second set of actors are the private investors who transform commercial districts from convenience stores, pawnshops, and check-into-cash counters into pedestrian-friendly streets of art galleries, yoga studies, and fine dining. High-end retail emerging in previously poor neighborhoods indicates a form of neighborhood change that requires profitable locations near a certain class of consumers. One such example would be the 1990s explosion of coffee shops in the U.S. as coffee shop giants and private entrepreneurs procured convenient storefronts in neighborhoods with residents willing and able to pay US$3 for a cup of coffee.

Figure 1 – Number of Coffee Shops by Type in Chicago, 1991-2004

Adapted from Papachristos et al. 2011

A third set of actors participating in the process of gentrification is the local and state political powers. Gentrification through state intervention includes rezoning, investments and permits in revitalization efforts, and the demolition of public housing. Public housing in the U.S. epitomizes decades of racial segregation, public disinvestment, concentrated poverty, and many devastating consequences. The Cabrini-Green housing projects of Chicago, for example, gained a national reputation of violence and danger following several high-profile murders including the 1992 murder of 7-year-old Dantrell Davis who was killed on his way to school by a stray bullet. In 2000, Chicago began its Plan for Transformation that included massive demolition efforts of public housing high rises. Today a Target shopping center stands where the Cabrini-Green high rises once stood.

In recent research, I show how each of these three gentrification processes affected the crime of gang homicide in Chicago from 1994 to 2005. My results were mixed. While the demographic shifts associated with gentrifiers and a count of neighborhood coffee shops associated with private investment both decreased neighborhood gang homicides over time, the demolition of public housing actually increased gang homicides in the short term.

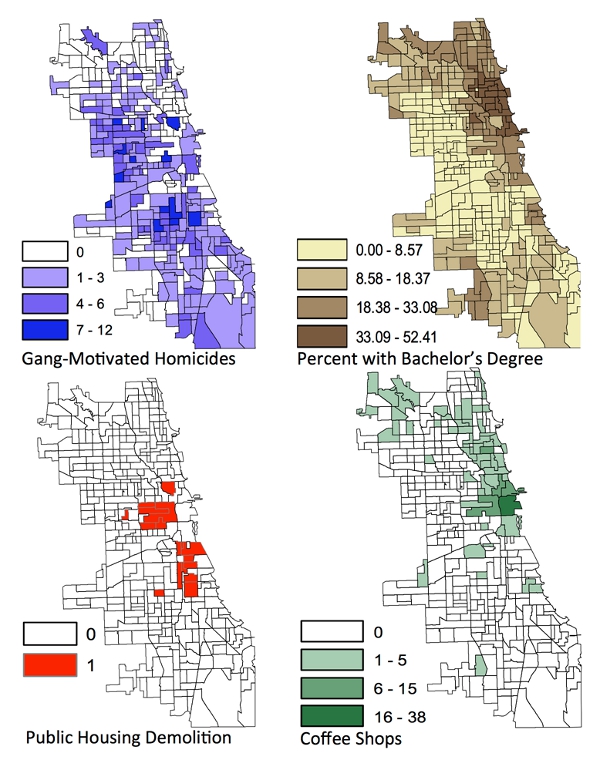

The map in Figure 2 presents this pattern descriptively showing that most coffee shop and high education neighborhoods were not the same neighborhoods with high gang homicides and public housing demolition.

Figure 2 – Maps of Chicago Neighborhoods, 2000-2005

Adapted from: Smith 2014

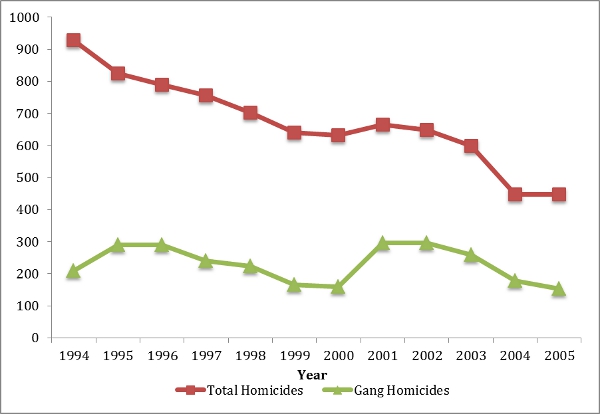

The Chicago Police Department distinguished these homicides as motivated by inter-gang and intra-gang violence. Official crime data seldom include motive, so this measure of crime is very insightful. Gang homicides tend to garner heightened media attention thereby increasing the general public’s fear of a neighborhood’s residents and provoking the neighborhood image as bad or dangerous. Gang homicides are particularly threatening because they most often involve guns and occur publicly on the streets. The victims are disproportionately young minority males and innocent bystanders. Though the total number of homicides decreased in the city of Chicago from 1994 to 2005, gang homicides did not follow the same pattern.

Figure 3 – Number of Total Homicides and Gang Motivated Homicides in Chicago, 1994-2005

Adapted from Smith 2014

Figure 3 shows an overall decline in Chicago homicides ranging from 928 in 1994 to 448 in 2005. The gang homicide line is much more sporadic. Comparing these two lines suggests that mechanisms driving down total homicides may not have had the same effect on gang homicides. In fact, the proportion of gang homicides to total homicides actually increased during this time. In 1994, gang homicides were 23% of Chicago’s total homicides while in 2005 gang homicides were 34% of Chicago’s total homicides. The highest proportion was in 2002 when gang homicides made up 46%—almost half of the city’s total.

Gentrifiers are not likely to be victims of gang homicide, but, from a policy perspective, gang violence dissuades private investment-style gentrification while encouraging state intervention such as the financial abandonment of gang-ridden public housing and eventual demolition of high rises. In other words, forced relocation rather than economic development might be one of the only tools of gentrification that can be used in a neighborhood with a severe gang problem—but at a cost.

Qualitative research in Chicago has detailed the ways in which public housing demolition devastates volatile gang boundaries and exacerbates gang violence creating a situation in which families fear moving into alternative housing. State efforts to revitalize crime-ridden areas are actually intensifying neighborhood crime conditions and increasing body counts, at least in the short term.

My research captures a unique historical moment in Chicago, 1994 to 2005, a period of increased gentrification and overall crime decline. However, the relationship between gentrification and crime remains unclear—my research and the research of other urban scholars have found mixed results on the relationship between gentrification and crime. The implication of all this is rather than treat gentrification as a silver bullet crime prevention strategy, we should investigate the characteristics that make gang homicide neighborhoods more volatile during public housing demolition. This approach would continue to serve at risk populations even after they have been relocated or displaced.

This article is based on the paper The Influence of Gentrification on Gang Homicides in Chicago Neighborhoods, 1994 to 2005 in Crime & Delinquency.

Featured image: Cabrini-Green prior to demolition CreditL Señor Codo (Creative Commons BY SA)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1npnuZF

_________________________________________

About the author

Chris M. Smith – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Chris M. Smith – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Chris M. Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her research areas include criminology, social network analysis, gender and crime, and urban sociology. Her dissertation examines women in organized crime networks from Prohibition-era Chicago.