One of President Obama’s most important tasks upon entering office in 2008 was the filling of more than 3,000 appointed positions within the federal government. But what governed these appointments, policy expertise or political reasons such as campaign experience? By studying more than 1,300 of Obama’s presidential appointments Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr., Gabriel Horton, and David E. Lewis find that he appointed individuals with policy expertise to agencies responsible for policies on his agenda and those who were more conservative. They write that more liberal agencies tended to have more appointees with campaign experience or political connections rather than policy expertise.

One of President Obama’s most important tasks upon entering office in 2008 was the filling of more than 3,000 appointed positions within the federal government. But what governed these appointments, policy expertise or political reasons such as campaign experience? By studying more than 1,300 of Obama’s presidential appointments Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr., Gabriel Horton, and David E. Lewis find that he appointed individuals with policy expertise to agencies responsible for policies on his agenda and those who were more conservative. They write that more liberal agencies tended to have more appointees with campaign experience or political connections rather than policy expertise.

Presidential appointees matter. One only needs to consider the United States government’s response to Hurricane Katrina to recognize that having agencies led by political appointees without relevant expertise can have disastrous consequences for citizens and the credibility of the presidential administration. Therefore, one of the most important tasks for new presidents is to fill more than 3,000 appointed positions within the federal bureaucracy.

From the perspective of presidents, the ideal appointee is one who is ideologically compatible, personally loyal, competent, and has the ability to further the electoral goals of the appointing president and his or her party. However, candidates who excel on all of these dimensions are few and far between, and so presidents must make tradeoffs between policy goals and political realities. This tension that has been recognized at least as far back as former president Woodrow Wilson’s seminal 1887 essay, “The Politics of Administration.” However, despite the long history in American presidential politics of using presidential appointments for patronage purposes, as well as the potential deleterious influence of patronage on the partiality and competence of government administration, the questions of how, when, and where presidents prioritize patronage considerations over other factors have been relatively understudied ones.

To address this, we amassed and analyzed new data on the backgrounds of 1,307 presidential appointments made during the first six months of the Obama administration. These data included information on whether or not the appointee had qualities one might reasonably link with policy expertise (e.g., having previous agency experience, having previous federal agency experience, having subject area expertise, etc.) and political expertise (e.g., having campaign experience, etc.). We looked for relationships between the relative types of appointee expertise and the types of agencies to which they tended to be appointed.

Our results suggest that, while President Obama likely had to make certain appointments for reasons outside of policy expertise, appointments of these types tended to be to agencies viewed as less important or more amenable to his policy goals. More individuals with demonstrated policy expertise were sent to agencies responsible for implementing policies on his agenda as well as agencies more resistant to his policy goals.

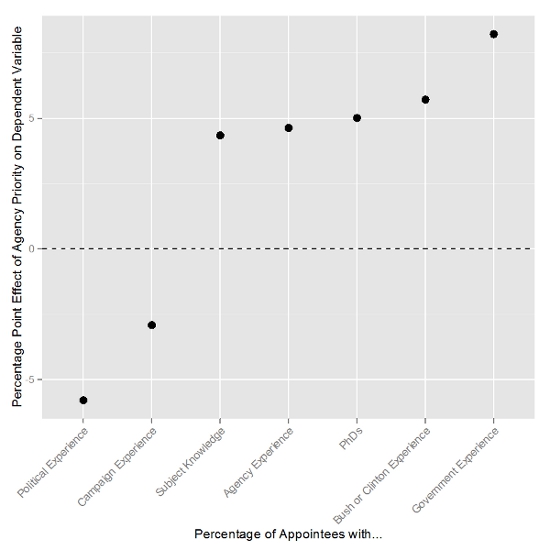

One of the first relationships we examined was that between competence and agencies responsible for policies on the president’s agenda, as determined by whether the agency was mentioned during his February 24, 2009 address before a joint session of Congress. The results from this analysis are rather striking. Generally, we found that agencies responsible for policies on the president’s agenda were more likely to be staffed with appointees with background characteristics we reasonably associate with competence, as showcased in Figure 1. For example, the proportion of appointees with PhDs in agencies on the President’s agenda was, on average, about five percentage points higher than the proportion of appointees with PhDs not on the agenda. Of course, we can’t be certain whether appointees with these background characteristics are truly more competent or simply credentialed but it is rather interesting that appointees with more background experience and education are generally more likely to work in agencies on the president’s agenda.

Figure 1 – Agency Priority and Appointee Types

However, the qualification of appointees is only one side of the story. Appointees with less competence are selected for another reason, namely campaign experience or connections. Indeed, we found that agencies on the president’s agenda were less likely to have high proportions of employees whose last job was in politics or who worked on the campaign. All else equal, agencies on the president’s agenda had rates of appointees selected for campaign experience or connections between four and six percentage points lower than those not on the president’s agenda. Collectively, these results add credence to the argument that presidents need appointees who not only support their initiatives but also have the skills to push for and execute new policies.

Of course, the above analysis raises a larger question—what types of appointees get put into positions with heightened expertise requirements? To understand this, we looked at the proportion of professional (as opposed to clerical or blue-collar) employees in an agency as a proxy for task complexity, under the assumption that the proportion of professional employees is an indicator of high agency task complexity, and therefore higher expertise requirements. We found that more professionalized agencies were linked to higher proportions of appointees with credentials reflecting expertise, suggesting that appointees with higher skill levels are necessary to manage agencies with complex tasks.

We also looked at the relative influence of appointees within agencies, using agency size as a proxy. In smaller agencies, each individual appointee will have more influence, on average, and we find that these agencies tended to have fewer appointees selected for political reasons, suggesting that people from the campaign or with a political claim on the administration may be easier to place in larger agencies where their influence is smaller and their presence is easier to accommodate.

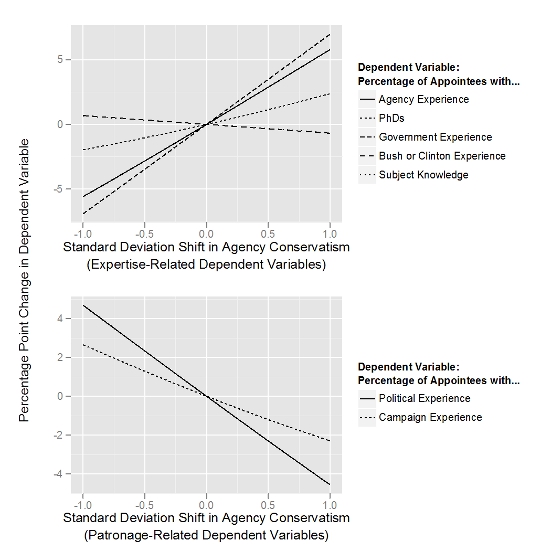

Finally, we looked at the role of ideology using Clinton and Lewis’s (2008) measures of agency ideology. As Figure 2 illustrates, we found that liberal agencies were less likely to have appointees with the background characteristics associated with competence and higher proportions of appointees with characteristics reflecting campaign experience or political connections. These findings seem to confirm that when presidents confront an agency that has policy views different from their own, they need appointees competent enough to bring change. In agencies that share the president’s views on policy, such as liberal-leaning agencies in the Obama Administration, career professionals are less likely to resist the direction of the White House, making the president’s management task easier and the competence of appointee management less crucial to the accomplishment of the president’s policy goals.

Figure 2 – Effects of Agency Ideology on Agency Characteristics

Our analysis here suggests that President Obama, when making appointments to those agencies high on his agenda and potentially resistant to his policy preferences, tended to focus on expertise and prior experience in addition to ideology. Indeed, these agencies—high-priority and conservative—received fewer appointees with demonstrated political credentials. Together, these findings suggest that appointing those with demonstrated or presumed competence—and not necessarily political experience—may be the method by which presidents seek to gain control over agencies and induce them to produce the policy outputs they prefer. However, greater proportions of appointees with demonstrated political credentials were named to less salient agencies and agencies more receptive to his policy goals. Of course, future research is needed, particularly research which differentiates among appointees with regard to loyalty and ideology.

What do these results mean for the ability of presidents to govern effectively? Our results are merely suggestive, but the signs are ominous. Indeed, the president’s success or failure depends in large part on the actions of the thousands of people managing day-to-day operations in the Department of Defense, emergency responses within the Department or Homeland Security, or the economy in the Treasury Department. However, if the personnel process, influenced by patronage pressures, diminishes the loyalty or competence of this team, this can have dramatic consequences for a presidency. Many of those selected primarily for campaign or political experience serve faithfully and well in obscurity but others end up causing significant damage to the country and the administration that appointed them, with potentially catastrophic results for the president and the nation.

This article is based on the paper ‘Presidents and Patronage’ in the American Journal of Political Science.

Image: President Barack Obama walks along the Colonnade of the White House with Chief of Staff Bill Daley and Office of Management and Budget Director Jack Lew, Jan. 9, 2012, before announcing Daley’s resignation and Lew’s appointment to replace him. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1oofKIw

_________________________________________

Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. – University of Georgia

Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. – University of Georgia

Gary E. Hollibaugh, Jr. is a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Public Administration and Policy at the University of Georgia, and will join the Department of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame as an assistant professor in July. He studies American politics and the interaction between the presidency and Congress, with a focus on presidential appointments.

_

Gabriel Horton – Vanderbilt University

Gabriel Horton – Vanderbilt University

Gabriel Horton is a research associate in the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions at Vanderbilt University.

_

David E. Lewis – Vanderbilt University

David E. Lewis – Vanderbilt University

David E. Lewis is William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt University. His research interests include the presidency, executive branch politics and public administration.

1 Comments