In 2005, Hurricane Katrina caused enormous devastation across the Gulf Coast of the U.S. But while many considered the hurricane to be a tragedy, in the aftermath, many city officials in the region saw it as an opportunity. Kate Derickson looks at how two Gulf Coast cities, Biloxi and Gulfport, used the destruction wrought by Katrina as an impetus for regional development. She writes that this development has been largely focused on poor African American neighborhoods that had already been squeezed by urban development strategies prior to the disaster, and that the nature of these neighborhoods helped to justify officials’ narrative that the storm had rendered them as ‘blank slates’.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina caused enormous devastation across the Gulf Coast of the U.S. But while many considered the hurricane to be a tragedy, in the aftermath, many city officials in the region saw it as an opportunity. Kate Derickson looks at how two Gulf Coast cities, Biloxi and Gulfport, used the destruction wrought by Katrina as an impetus for regional development. She writes that this development has been largely focused on poor African American neighborhoods that had already been squeezed by urban development strategies prior to the disaster, and that the nature of these neighborhoods helped to justify officials’ narrative that the storm had rendered them as ‘blank slates’.

A curious thing happened after Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast of the United States in 2005. In the cities of Gulfport and Biloxi, Mississippi, 90 miles east of New Orleans, city officials and business leaders spoke of the storm not as a tragedy, but rather an opportunity. Standing on the beach looking north toward devastated neighborhoods still little more than rubble dotted with trailers from the Federal Emergency Management Agency six months after the storm, this claim was perplexing. Yet one only had to look south, to the glittering high rise resort-style casinos built back “better than ever” to begin to get an inkling of the nature of this so-called opportunity. The city of Gulfport’s website beckoned potential developers:

“Like the artist with the blank canvas or an explorer who steps foot in a brand new land – as residents of Gulfport, Mississippi, we eagerly await the authors who will write the future chapters of our beloved hometown… From the fury of Mother Nature comes the opportunity to redefine our city as a progressive new enterprise of hope and prosperity. When you bring your vision to the shores of Gulfport, you will take your place among the other captains and watch your own ship come in” (City of Gulfport, 2010).

In short, the storm had accomplished what the region’s elites could not have otherwise done, creating the conditions under which rapid and sweeping redevelopment and gentrification were possible.

The notion the region was wiped clean, at least in some places, set the stage for a host of urban design and economic development challenges the cities had been pursuing in the years leading up to the storm. Once known as the seafood capital of the world, the Coastal Mississippi cities of Biloxi and Gulfport had been stumbling to find economic footing in the wake of a near collapse of the boat building, fishing, and seafood processing industries in the late 1970s. The evolving economic development strategy of the region had coalesced around a characteristically neoliberal set of urban redevelopment strategies, including place-promotion, high-end consumerism, state-led infrastructure investment to promote business, and low taxes.

The often-cited goal, repeated in numerous interviews with various members of what Molotch would call the regional growth machine, was to transform the region into a Tier One destination. Though there does not appear to be a technical definition of a Tier One destination, those promoting this vision most often referenced airport capacity and connectivity, numbers of hotel rooms, quality of tourist attractions, availability of high-end branded casinos and golf courses, and conference hosting capacity as elements of the larger vision.

The prospect of the Mississippi Gulf Coast as a top tourist and conference destination turned primarily on a growing casino industry in the region. In 1990, the Mississippi State Legislature passed critical legislation to allow individual counties in the state of Mississippi to authorize casino gaming, with a restriction requiring that gambling floors be located on navigable waters. This restriction ensured that casinos would not be able to dominate the landscape of the entire state, but it also meant that key pieces of property along the Gulf Coast that were home to now defunct seafood processing plants would be substantially more valuable as casinos sought to assemble parcels zoned to allow gaming. Notably, the legislation was shepherded by Tommy Gollot, a Biloxi representative who, along with his brothers, owned large swaths of land along the coast and has since collected substantial rents from casinos.

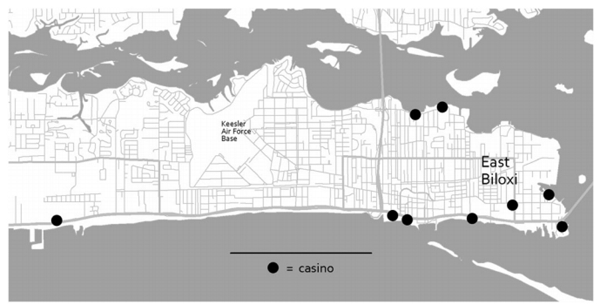

By the time Hurricane Katrina hit, there were 9 casinos forming a ring around the eastern peninsula of the city (Figure 1). Yet while the casino industry was thriving to the point that the mayor of Biloxi had declared the city in the midst of a “renaissance” the landscape of East Biloxi and much of Gulfport remained wildly uneven, still bearing the scars of over a century of institutional racism. During reconstruction, African Americans in the region took advantage of the Swamp Lands Act to purchase swamp land, often in the backwaters and bayous set away from the whites-only areas along the coast.

Figure 1 – Casino locations in East Biloxi

Map by Paolo Raposo.

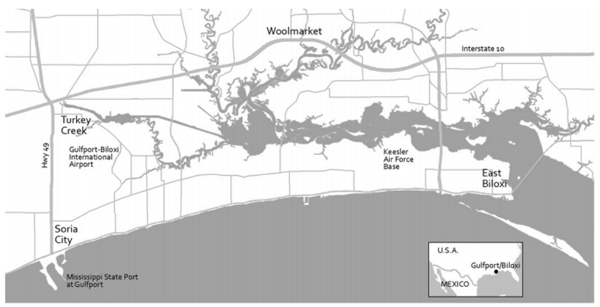

Natural and human-made features of the landscape served as de facto dividing lines and created pockets of African American settlement that endure today. African Americans remained heavily concentrated in neighborhoods that had been the historic centers of African American life during reconstruction, Jim Crow, and in pre-Katrina Mississippi. Neighborhoods like Biloxi’s Back Bay and Gulfport’s Soria City, North Gulfport, and Turkey Creek were home to a disproportionate concentration of the region’s African Americans and were all majority African American, a notable concentration in an area where African Americans made up less than 30 percent of the population (Figure 2). The east-west railroad divided the beachfront from the back bays and bayous, setting Soria City and Back Bay apart (Figure 2), while Turkey Creek represented a Swamp Land acquisition of what the neighborhood’s folklore calls “eight forties” in reference to the promise of forty acres and a mule to freed slaves.

Figure 2- Historic African American neighborhoods in Gulfport and Biloxi, Mississippi

Map by Paolo Raposo.

Prior to Katrina, in Harrison County, which includes both Gulfport and Biloxi, 27 percent of the African American population lived in poverty, the 2000 US census showed that whereas only 10 percent of the white population were poor. Median household income for white families was $38,353 in 2000, compared with $29,394 for African American families. Data from the 2010 census show an even starker divide, with median household income for whites increasing at a rate of 33 percent since 2000 (to $50,903), with African American household income increasing at just 3.6 percent to ($31,013). Further, the neighborhoods associated with low-income and poverty status are also the historic centers of African American life in the region. Thus, when the specter and pathologies of low-income housing and families are raised in the redevelopment process, race is implicated as well.

Prior to the storm, each of these neighborhoods were feeling squeezed by urban development strategies meant to realize the new vision for the region. Turkey Creek and North Gulfport were surrounded by an interstate, the airport, a creosote plant, and a polluted creek prone to flooding, and targeted for a new road that would fill in wetlands to connect the State Port to the Interstate. Soria City was also in this path and adjacent to the industrial port. The Back Bay of Biloxi was directly in the middle of the casino development. Thus, the storm did not come ashore in a post-racial space; neither did it create one, despite the refrain often defensively repeated in interviews and closed-door meetings that the storm did not discriminate. In fact, analysis by the Mississippi Center for Justice suggests otherwise. The Center found that 95 percent of residents of the most heavily impacted areas of Biloxi earned below federal median income, and 80 percent of these residents suffered extensive or catastrophic damage. The most heavily African American census tracts in the cities of Gulfport and Biloxi faced the highest surge elevations of 16 – 22 feet.

In light of the uneven impact of the storm and the fact that these neighborhoods were located adjacent to areas designated for high end use, the giddiness with which regional boosters declared that the storm was, in effect, an opportunity, can be newly interpreted. In the same way that the racialized concept of blight justified and created opportunities for new forms of urban development under the guise of urban renewal in the post-War era the highly racialized and impoverished nature of these neighborhoods worked to justify and enable the narrative that the storm had rendered them blank slates, and in so doing, created new opportunities for intensifying and further accomplishing the vision of the city promoted by regional boosters.

This article is based on the paper ‘The Racial Politics of Neoliberal Regulation in Post-Katrina Mississippi’ in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

Featured image credit: Michael Muniz (Creative Commons BY NC ND)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/TYLSYL

_________________________________

Kate Derickson – University of Minnesota

Kate Derickson – University of Minnesota

Kate Derickson is an Assistant Professor of Geography, Environment and Society at the University of Minnesota. Her research interests include racialization, urban political economy, and community-based activism. She has worked extensively with historically marginalized communities in Mississippi, Atlanta, and the Govan neighborhood of Glasgow, Scotland. Her work has been published in academic journals, including the Annals of the Association of American Geographers and Progress in Human Geography.