In this book Zaid al-Ali sets out why and how the post-occupation Iraqi government has failed to achieve legitimacy or improve its citizens’ lives, covering how corruption has prevented aid and oil income making a difference to security, healthcare and power. Vivid descriptions of the extent of violence and low quality of life that became part of everyday life in Iraq are remarkable and give the reader a much closer understanding of what Iraqis, especially in Baghdad, have been going through, writes Zeynep Kaya.

The Struggle for Iraq’s Future: How Corruption, Incompetence and Sectarianism Have Undermined Democracy. Zaid Al-Ali. Yale University Press. 2014.

The Struggle for Iraq’s Future: How Corruption, Incompetence and Sectarianism Have Undermined Democracy. Zaid Al-Ali. Yale University Press. 2014.

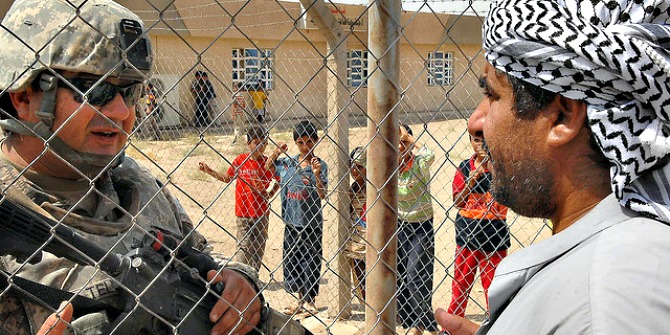

The rise of ISIS in parts of Northern Iraq and the possibility of a breakaway of the Kurdish region from the central Baghdad government make questions about Iraq’s future more prescient than at any stage since the 2003 invasion. If Zaid Al-Ali’s central claim in his book The Struggle for Iraq’s Future is accepted, Iraq’s position today could be entirely different if the artificiality of sectarianism was understood and if today’s political elites could act beyond their short-term interests. Al-Ali provides a detailed account of the downward progression of the state of affairs in Iraq, offering readers illuminating explanations of the political, economic and social context of the increasing sectarian rift that has led to today’s turmoil.

Al-Ali, a lawyer who specialises in comparative constitutional law and international commercial arbitration, explains how hopes for Iraq to become a freer and more prosperous country faded over a ten-year period following the collapse of Ba‘ath regime. Particularly focusing on the period since 2005 when the Iraqi constitution was drafted, he provides a forensic and compelling account of the constitution-making process and the substantial issues within the constitution that set the ground for the political turmoil which followed. In more general terms, Al-Ali compares pre-2003 and post-2003 Iraq, which helps the reader to identify the long-term and short-term problems Iraqi politics and society have been experiencing.

There can be little doubt that this book is more suitable for those who already have a relatively good understanding of Iraqi politics and society, the political divisions among parties, and the process of intervention. Having said that, the opening two chapters, ‘A legacy of oppression and violence’ and ‘The origins of the political elite’, offer a lucid and accessible background for the general reader. Combined, these chapters cover Iraqi politics before the collapse of Saddam Hussein’s regime and outlines the origins of the new political elite (who are mostly once exiled Iraqis), and the design of the Iraqi constitution. This background frames subsequent discussions of the rise of al-Maliki and his return to sectarian-style politics after 2010. The remainder of the book, however, is aimed at readers interested in an in-depth look into the thinking and actions of the key actors, the working of the newly established government and its ministries, and the events that took place within the last decade.

A central contention of the book is that while an increasing number of Iraqis complained about the government’s performance and poor services, Iraq’s ruling class used sectarianism to consolidate their positions of power and to place their members in senior positions in society. Thus sectarianism became the foundation of the country’s political order. The Struggle for Iraq’s Future should not be seen simply as a critique of al-Maliki’s policies. Al-Ali addresses a wide range of issues that led to the political crisis in Iraq, from the ineptitude of the political elite, the extent of corruption, and the incorrect assumptions and ignorance of the international involvement. The focus on issues with utility services such as electricity and water, and on a deteriorating environment and health is very insightful and provides a fresh and realistic understandings of Iraq today as opposed to most writings on Iraq that solely focus on politics and security.

Al-Ali also illustriously demonstrates the inability of the occupying forces and the new political elite to build on the existing institutional structures and experience. He argues that the removal of experienced technocrats and bureaucrats for various futile reasons, the incompetence of the new members of the administration and the political cadre, corruption and a lack of accountability at all levels of politics, immensely contributed to the troubles experienced in Iraq. Vivid descriptions of the extent of violence and low quality of life that became part of everyday life in Iraq are remarkable and give the reader a much closer understanding of what Iraqis, especially in Baghdad, have been going through. This scene is further illuminated by the accounts of individuals and their reaction to the transformation of their lives since the intervention. The author’s personal account of his experience and observations working and living in Iraq makes the book an interesting read.

The Struggle for Iraq’s Future is driven by Al Ali’s frustration with the Iraqi political elite, the massive mistakes made by the occupying forces, and the suffering of the Iraqi people both before and after 2003. Having worked as a legal adviser to the United Nations in Iraq from 2005 to 2010, gives the author privileged insights into the drafting of the constitution and the reasons behind seemingly small individual decisions that had huge impact. The depth of detail provided in the book and the forensic analysis of constitution-making process and Iraqi politics cannot be faulted and are largely illuminating and insightful. Yet, as with any heavily descriptive and in-depth analysis, the reader gets lost at times in the scattered and slightly disorganised information, and the structure can leave readers yearning for a more thematic and organised read.

The slightly difficult and intense chapters do not detract from the biggest strength of the book, however, which is the way in which it conveys how sectarian divisions increasingly dominated all aspects of political life in Iraq from the prime-ministerial elections to the organisation of administration and the daily lives of the individuals. For Al-Ali such divisions emerged from artificial arguments about the historical persistence of sectarianism in Iraq and the profoundly destructive impact of the adoption of sectarian rhetoric by the new Iraqi political elite and international actors. Through comprehensive descriptions and anecdotes, Al-Ali draws on a compelling array of evidence to show how non-sectarian affiliations were increasingly replaced by sectarian, ethnic and religious affiliations. As such, Al-Ali’s insightful account fills a gap in the literature by providing an important critique of the bad decisions made along the way in rebuilding the Iraqi political system and of the argument that history of sectarianism is inevitable.

This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1sASDgb

——————————————–

Zeynep Kaya – LSE Middle East Centre

Zeynep Kaya – LSE Middle East Centre

Dr Zeynep Kaya is a Fellow at the London School of Economics. She completed her PhD in International Relations at LSE on the interaction between international norms and ethnicist conceptions of territorial identity with a focus on the Kurdish case. She is currently working on her book titled The Idea of Kurdistan: International Norms and Nationalism for the University of Pennsylvania Press. Read more reviews by Zeynep.