While food insecurity in America is by no means a new problem, it has been made worse by the Great Recession. Now, about 49 million people in the U.S. are living in food insecure households, and nearly 47 million receive assistance from national food banks. Looking at the results of Feeding America’s Map the Meal Gap study, Elaine Waxman, Amy Satoh & Craig Gundersen write that unemployment is a major driver of the food insecurity which exists in every county in the U.S. They argue that food insecurity can be addressed through improving people’s participation in federal food assistance programs, especially among children.

While food insecurity in America is by no means a new problem, it has been made worse by the Great Recession. Now, about 49 million people in the U.S. are living in food insecure households, and nearly 47 million receive assistance from national food banks. Looking at the results of Feeding America’s Map the Meal Gap study, Elaine Waxman, Amy Satoh & Craig Gundersen write that unemployment is a major driver of the food insecurity which exists in every county in the U.S. They argue that food insecurity can be addressed through improving people’s participation in federal food assistance programs, especially among children.

Addressing the challenge of hunger in a wealthy, developed nation like the United States requires a thorough understanding of the complexities of the problem. In September of 2014, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) released its most recent report on food insecurity, indicating that approximately 49 million people in the United States are living in food insecure households, nearly 16 million of whom are children. Food insecurity has persisted at this high level since the Great Recession, and in August 2014, the nation’s largest domestic hunger organization, Feeding America, reported that it is now serving 46.5 million people annually through its nationwide network of food banks. While the magnitude of the problem is clear, national and even state estimates of food insecurity can mask the variation across the country. In the absence of meaningful local data, it is difficult to educate the public and policymakers on the existence of hunger or to target services efficiently based on unique local conditions.

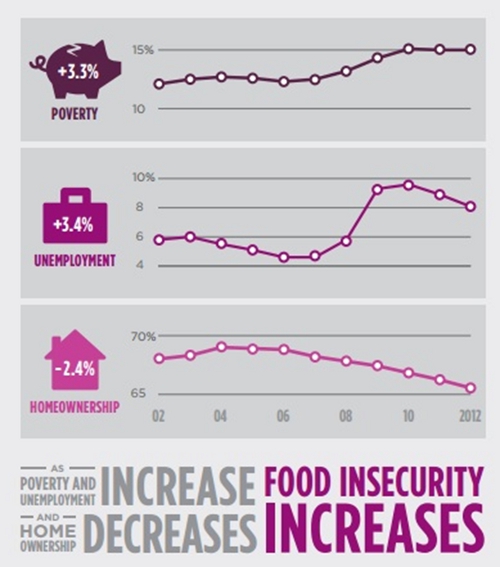

Prior to the inaugural Map the Meal Gap (MMG) release in 2011, Feeding America used state and national level USDA food insecurity data to estimate the need and food banks often turned to county-level poverty data in an effort to estimate the demand for charitable assistance in their local communities. However, poverty statistics alone are an insufficient proxy for food insecurity – more than half of all food insecure households in the country have incomes above the federal poverty level. While poverty is an important underlying factor in food insecurity rates, results from Map the Meal Gap 2014 indicate that across all 3,143 counties, unemployment is the primary driver in variation in food insecurity, as Figure 1 shows. A one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to a 0.51 percentage point increase in food insecurity, while a one percentage point increase in the poverty rate leads to a 0.19 percentage point increase.

Figure 1 – Food insecurity, poverty, unemployment and homeownership

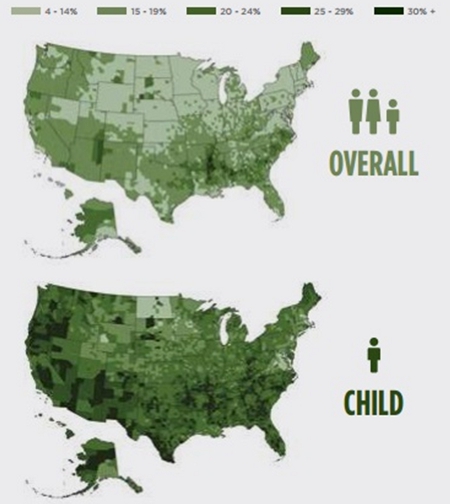

MMG generates four types of community-level data: food insecurity estimates, child food insecurity estimates, a food price index, and a food budget shortfall. More accurate assessments of food insecurity within our service areas assist the Feeding America network in strategic planning for charitable services, as well as inform the public policy discussion on vital federal nutrition programs.

Figure 2 – Percentage of people per county who are food insecure

Among the key insights from the report is that food insecurity exists in every county across the country, ranging from a low of four percent in Slope County, North Dakota to 33 percent in Humphreys County, Mississippi. Even within a single state, county level food insecurity rates may vary widely: for instance, food insecurity rates range from five percent to 26 percent in Virginia and from seven percent to 30 percent in Louisiana.

Additionally, by estimating the income resources of the food insecure population at the local level, MMG supports communities in assessing potential strategies that can be used to address hunger. For many households, the first line of defense can be federal nutrition programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and child nutrition programs like the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) or the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). Income eligibility for these programs is tied to multiples of the federal poverty line (FPL). State-specific eligibility ceilings for SNAP range from 130-200 percent of FPL, while WIC and reduced price lunches are typically not available for children in households with incomes above 185 percent of poverty.

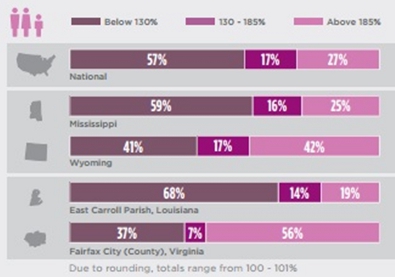

In 2014, the federal poverty guideline for a family of four in the lower 48 states was a pre-tax income of $23,850 – at 130 percent of gross income, the SNAP ceiling would be $31,005. However, as Figure 3 shows, approximately 26 percent of all food-insecure people in the United States in 2013 lived in households with incomes above 185 percent of the poverty line and thus, were likely ineligible for most food assistance programs. For these families, charitable organizations are typically the primary resource available beyond the help of family and friends. Indeed, across the country, there are 141 counties where the majority of food-insecure people are likely ineligible for government assistance programs based on their household income, and most states have counties where the majority of food-insecure people are likely SNAP eligible alongside counties where the majority of food-insecure people are likely ineligible for any federal nutrition assistance. By illuminating these income disparities, MMG underscores the critical role of charitable assistance and the need to strengthen anti-hunger programs and policies in order to address food insecurity in America.

Figure 3 – Overall food insecurity and income level variation

Existing federal nutrition programs could do more to address food insecurity simply by improving outreach to and participation of those who are currently underserved. For instance, SNAP, which is the key component of any effort to reduce food insecurity in the United States. Despite the proven ability of SNAP to reduce food insecurity, over one-in-five eligible households do not participate.

The National School Lunch Program is also an important component of efforts to reduce food insecurity, as is the School Breakfast Program. As with SNAP, there is room for improvement in participation rates in the School Breakfast Program in particular. Although more than 21 million children received free or reduced-price lunches in 2013, only 11 million received breakfast. In addition to encouraging efforts to increase participation during the school year, extension of food assistance to school children during the summer is also critical asonly 2 million children received food assistance during the summer.

Recent evidence has also found that WIC leads to reductions in food insecurity. Participation is high among infants – 83 percent of eligible infants receive WIC benefits – but it is not nearly as high among eligible children aged one through four (54 percent), and participation rates are especially low among older children. Efforts to increase participation, including changes in the structure of the program to make it more appealing to older children, are encouraged.

Improved program access and innovative delivery models can also help improve participation. There are only about 43 summer food sites for every 100 school lunch programs nationwide. In addition to increasing the number of summer feeding sites, flexibility in implementing alternative summer delivery models can also increase program reach, e.g. strategies such as delivering meals directly to low-income neighborhoods rather than requiring families to find transportation to a summer site or allowing families to pick up a week’s worth of meals to eat at home rather than requiring children to travel to the site each day can help communities better reach those in need.

The Map the Meal Gap research is intended to shed light on the issue of food insecurity as a problem that exists in all localities across the United States. We encourage others to examine how local-level food insecurity data relates to other indicators of community well-being, such as health data, housing costs, and other economic measures. It is our hope that better local data can more effectively equip policy makers, program administrators, business leaders and concerned citizens to strengthen the fight against hunger in the United States.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Map the Meal Gap: Exploring Food Insecurity at the Local Level’in Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy.

Featured image credit: Anna Vallgårda (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1BICxoR

_________________________________

Elaine Waxman – Feeding America

Elaine Waxman – Feeding America

Elaine Waxman is Vice President of Research and Nutrition at Feeding America, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief charity. She has over 20 years of experience in public policy research and consulting and oversees numerous studies on food insecurity, client coping strategies, and charitable food assistance. Dr. Waxman received her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration.

Amy Satoh – Feeding America

Amy Satoh – Feeding America

Amy Satoh is a Manager of Social Policy Research and Analysis at Feeding America, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief charity. Her research projects are focused on food insecurity and related coping strategies of low-income populations including federal nutrition programs and charitable food assistance. She received her master’s degree from the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration.

Craig Gundersen – University of Illinois

Craig Gundersen – University of Illinois

Craig Gundersen is the Soybean Industry Endowed Professor of Agricultural Strategy in the Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics at the University of Illinois and Executive Director of the National Soybean Research Laboratory. Gundersen’s research is primarily focused on the causes and consequences of food insecurity and on evaluations of food assistance programs.

2 Comments