President Obama faces both a Republican House and Senate, potentially reducing significantly his power over the legislature. Could the increasingly unpopular Obama still exercise some degree of influence through his State of the Union address? Using more than 60 years of data on Congressional policy agendas and the State of the Union John Lovett, Shaun Bevan, and Frank Baumgartner find that the president is more able to influence congressional committees soon after the State of the Union, when they share the same party, and when the president is popular. They also find that this influence is greater over the House than the Senate.

President Obama faces both a Republican House and Senate, potentially reducing significantly his power over the legislature. Could the increasingly unpopular Obama still exercise some degree of influence through his State of the Union address? Using more than 60 years of data on Congressional policy agendas and the State of the Union John Lovett, Shaun Bevan, and Frank Baumgartner find that the president is more able to influence congressional committees soon after the State of the Union, when they share the same party, and when the president is popular. They also find that this influence is greater over the House than the Senate.

- This article was first published on November 11th, 2014.

With both House in the United States Congress to return to Republican control for the first time since 2007 in the wake of this year’s midterm elections, one would wonder to what extent President Barack Obama will be able to influence Congress to focus on his priorities. The new reality of a Republican-controlled Congress, something President Obama has not faced in his time in the Oval Office, seemingly could mean a body that simply ignores the president’s priorities entirely. However, it may also be the case that the control may not matter for attention: Obama, a president with middling approval, may be ignored regardless of who controls Congress.

In new research, we use the president’s State of the Union (SoU) address to assess whether the president’s issue priorities influence changes in the attention Congress gives to presidential priorities. We find that the president’s power to influence congressional committees depends on four factors: 1) whether the president and Congress share the same party; 2) the president’s public approval level; 3) the amount of time that has passed since the speech was given; and 4) whether we are discussing the House or the Senate.

First, a president who shares the party of the majority of the congressional body (united government) will be more successful at influencing Congress than a president of the rival party. The president, as leader of their party, will be giving directions to their members of Congress, and that influence will lead to similar priorities. A president acting under united government then will be more successful at influencing Congress than one who acts under divided government. No surprise there.

Second, popular presidents will generally have a more effective bully pulpit than unpopular presidents. Members of Congress will want to accede to the priorities of a popular president, knowing that following a president’s priorities may help advance their own ambitions. More popular presidents will then be more successful at getting congressional attention than unpopular presidents. In fact, unpopular presidents have no effect, no matter which party they are from; they are simply irrelevant to Congressional priorities, in united or divided government.

Third, a speech’s influence will wane over time. As new priorities and new events enter the sphere of congressional attention, older events will fade and committees will move onto the new topics. The result is that the effects of a president’s speech on congressional attention will dissipate over the course of the rest of the year. Even a popular president with partisan control of Congress has little impact over the long-term.

Finally, the two bodies should act differently, with the House generally more likely to focus on presidential attention than the Senate. The House and its adherence to the power of the majority should respond more forcefully to a president’s priorities, while the Senate’s more independent nature leads to decreased effects.

To test these factors, we compiled data on the State of the Union and congressional hearings using data from the Policy Agendas Project. We employ topic identifiers used by the Policy Agendas Project to test changes in attention to different topics over time. Our dependent variable is the proportional change in congressional hearings, and our main independent variable is the percent of space a president gives to a specific topic in the SoU. We also employ a series of interactions to test the effects between the SoU and presidential approval at the time of the SoU as well as the SoU and divided government, as well as controls on media and public opinion.

Our model employs a time series cross-sectional design, testing in terms of 19 Policy Agendas Project topic areas over a 53 year period (1953-2007). Separate models are used to test on the House and Senate. In addition, we also run separate models to test the proportional change in the number of hearings 3 months following the SoU (February-April), the remaining 8 months of the year (May-December), as well as for the entire year. The result is 12 models depending on variation in body, government, and time.

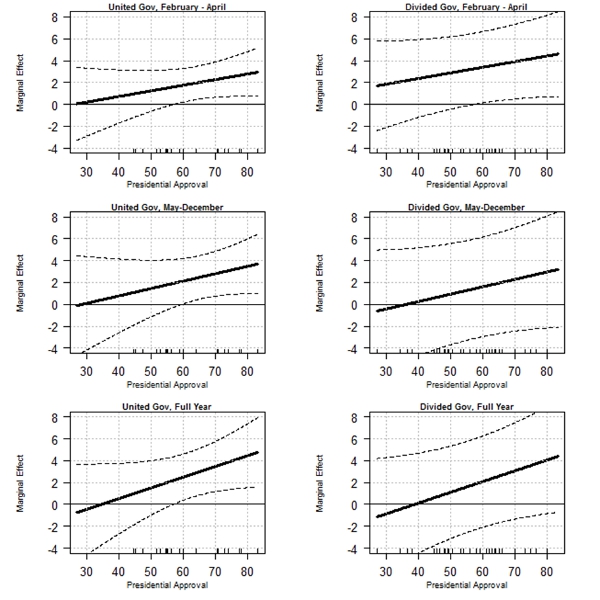

In Figure 1, we present results from the House models. The results are presented as marginal effects graphs, which show the effect a 1 percent increase in the space a topic is given in the SoU has on the proportional change in committee attention to that topic. The effect is graphed across the level of presidential approval. Each graph represents a separate model, with the columns representing united and divided government, and the rows representing different times of year. 95% confidence intervals are used to track significance across each graph. Finally, we use a rug plot to represent actual presidential approval numbers.

Figure 1 – Predicted Effects on Congressional Attention by Approval, Divided Government, and Time, House

The results show support for the conditional role of approval, especially early in the year, when effects are strongest. A president with a high level of approval will be able to influence congressional committees to commit attention to a president’s priorities. An unpopular president, on the other hand, will have no effect on committee attention to issues. Popular presidents can influence committee attention, while unpopular presidents are simply ignored.

These effects also outweigh the effects of united and divided government, as we find significant effects for both united and divided government at high levels of presidential approval, as members of both parties want to see themselves as dealing with the issues of a popular president. We do however see these effects dissipate in the divided government case, giving credence to the differences between united and divided government. Finally, we find support for the dissipation of effects in divided government, but do not find effects for united government, as presidents seem to be effective at keeping their own party’s attention to their topics throughout the year.

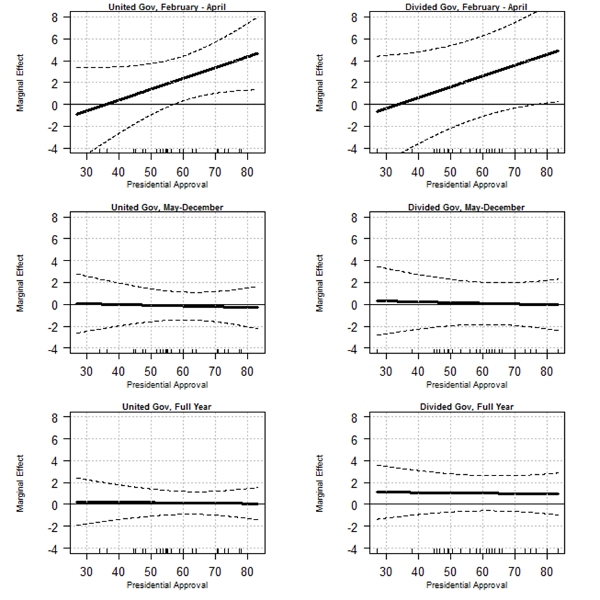

Next we turn to the Senate, which is presented in Figure 2 in the same format as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 2 – Predicted Effects on Congressional Attention by Approval, Divided Government, and Time, Senate

Unlike Figure 1, we find significant effects in the first three months for united government starting around 60%, while in divided government we only find effects at the highest possible levels of approval. In both, we also find effects dropping off entirely following the first 3 months, implying that the Senate’s nature as an independent body takes over after a brief period, and that as a result a president’s SoU has limited power, regardless of presidential approval.

The results here show conditional relationships between presidential and congressional attention. A popular president will have the ability to influence the House and Senate to orient attention toward the president’s priorities early in the year, while an unpopular president will simply be ignored. However, as the year goes on, new priorities take over and the president’s SoU will have decreasing impact. President Obama will give his seventh State of the Union in 2015. With his current approval hovering in area around 40 percent, it is likely that control of Congress will not change the amount of attention his SoU receives from committees. As a president with middling approval, he will simply be ignored regardless of which party controls Congress.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Popular Presidents Can Affect Congressional Attention, for a Little While’ in the Policy Studies Journal.

Featured image credit: The White House.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1u5wbOI

_________________________________

John Lovett – University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

John Lovett – University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

John Lovett is a graduate student at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, specializing in American Politics. His dissertation focuses on the notion of party branding and rebranding, and what conditions cause political parties to shift their issue priorities.

_

Shaun Bevan – Mannheim Centre for European Social Research

Shaun Bevan – Mannheim Centre for European Social Research

Shaun Bevan is a Research Fellow at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES) at the University of Mannheim. Shaun’s research interests focus on American, British and Comparative Politics, as well as Political Methodology. Some of his specific interests include agenda-setting, public policy, interest groups, public opinion, time series analysis, event history analysis and measurement.

Frank R. Baumgartner – University of North Carolina

Frank R. Baumgartner – University of North Carolina

Frank R. Baumgartner is the Richard J. Richardson Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the co-author of Agendas and Instability in American Politics and other works.