One major effect of the recent US government shutdown has been the delay of the annual State of the Union, the President’s set-piece speech before a joint session of Congress. John Lovett writes on the history and meaning of the President’s address, reminding us that the US Constitution offers little specific guidance on the format and timing of the State of the Union. While the State of the Union is usually aimed at influencing Congress, he argues, unpopular presidents – like Donald Trump is now – often have their agendas largely ignored.

One major effect of the recent US government shutdown has been the delay of the annual State of the Union, the President’s set-piece speech before a joint session of Congress. John Lovett writes on the history and meaning of the President’s address, reminding us that the US Constitution offers little specific guidance on the format and timing of the State of the Union. While the State of the Union is usually aimed at influencing Congress, he argues, unpopular presidents – like Donald Trump is now – often have their agendas largely ignored.

On January 25, 2019, after weeks of back-and-forth between President Trump and newly-installed Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, the partial shutdown of the United States government begun the previous year ended with the president agreeing to sign a continuing resolution to reopen the government. This agreement did not include funding for his main immigration policy desire, a wall on the border between the United States and Mexico. The debate between Republicans and Democrats (though in particular Trump and Pelosi) highlighted a variety of issues within American politics. In particular, the showdown highlighted the limits of presidential power for an unpopular president, as the president, after five weeks of negotiations and debate, was unable to get his primary priority despite for at least part of the period having control of both houses of Congress.

In addition to the end of the shutdown, one important concession the president was unable to gain from Congress and Speaker Pelosi was on the State of the Union speech. The State of the Union, the central policymaking address given to Congress, is normally given by the president in January, with the fiscal year budget first introduced by the president on February 15. After initially scheduling the State of the Union for January 29, Speaker Pelosi first suggested moving the State of the Union to after the shutdown due to security concerns, and then, after President Trump attempted to continue to go ahead with the speech, formally disinvited the president to speak until after the end of the shutdown.

That being said, the debate over timing of the State of the Union is one that does allow us to ask some questions. First, who actually has control over the timing of the State of the Union itself, and second what is the overall purpose of the State of the Union?

Congress is in Control

The Constitution offers us some guidance on the first question in terms of what it does not say. Article II, Section 3 notes “He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” While this section does note that the president shall from time to time give a sense of priorities to Congress, it does not say how the State of the Union shall be given, or when, or even where. While the president is supposed to relay these priorities from time to time, it does not mean it has to be live in front of Congress. Theoretically, the president could deliver the speech in any manner he wishes: from the Oval Office, from the Rose Garden, on Twitter, or through the broadcast of CBS’ coverage of the Super Bowl with commentator Tony Romo predicting what the president says next.

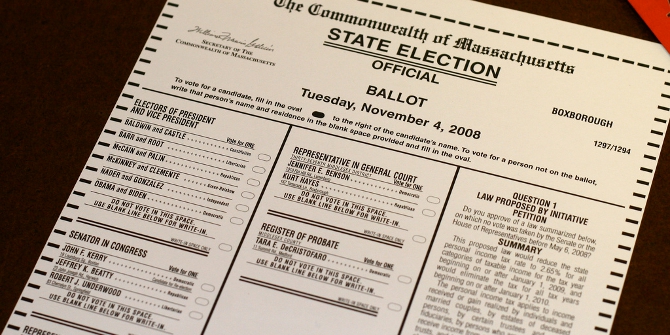

“State of the Union” by The White House is Public Domain.

As the Constitution offers little guidance on how, when, or where it is given, we much look to history for the developed tradition of the speech. After Thomas Jefferson ended the practice in 1801, started by George Washington of giving the address in person to the House, presidents up to 1912 simply sent a letter to the House, which was then read by a clerk. The tradition of coming to Congress only returned with the election of President Woodrow Wilson in 1913, with the speech not being televised until Harry Truman’s 1947 speech. Today, the speech receives significant coverage, as 45 million people watched the speech in 2018, a number only topped in 2018 by NBC’s broadcast of Super Bowl LII.

In addition, it is up to the Speaker of the House to determine when the president can give the speech and allow for the usage of the House chamber and technology related to giving the speech. As part of the process for the speech, the House and Senate pass concurrent resolutions to allow the president to speak in the chamber. While the president would have been able to enter both Congress and get onto the House floor, parliamentary rules would likely have restricted his ability to give a speech without expressed consent from Congress.

A speech to get things done, but presidential popularity is a key factor

We have a good understanding of what the speech is and some of the history, but what is the purpose of this speech? Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution can offer us more insight, with its mention of “recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” Simply, the president presents his governing priorities to the nation. Yet, should Congress care? As I (with my co-authors Shaun Bevan and Frank Baumgartner) have discussed previously here, presidential success at influencing Congress using the State of the Union depends on two main factors: presidential approval and the time since the speech given. Popular presidents get things done and move Congress to hold hearings on topics of importance to the president, while unpopular presidents are unable to move Congress. In addition, these effects are fleeting, with other priorities eventually overriding initial presidential priorities.

While our data analysis ended in 2007, we can at least take the lessons from this work and apply them to the modern day, in particular the question of approval. Generally speaking, President Donald Trump is an unpopular president. President Trump’s opinion numbers currently average out at 39.4 percent as of January 27 according to FiveThirtyEight’s analysis, and even in the poll that consistently gives Trump the most positive ratings, Rasmussen Reports, he has not topped 50 percent total approval in polling since December 7 and the latest polling puts him at 45 percent approval. Considering that we find that a president likely needs to have an approval of around 60 percent to influence Congress to focus hearings on a president’s priorities, it is unlikely that the president’s statements will have any effect on the activity of either the House or Senate.

In general then, why all of this discussion over a speech when it will have little influence on Congress or the general public? Why not simply submit the letter and be done with it? For one, the tradition of giving the State of the Union to a national audience is hard to break: it’s as expected in American politics as the conventions, the debates, and other measures that may feel like relics of history. Equally important is that this president is uniquely interested in media coverage. Trump’s renewed popularity was born from media (in the form of the NBC series The Apprentice) and he has used media to promote himself and his thoughts throughout the last decade. The opportunity to be seen in millions of houses is one that this president would likely not miss, regardless of how many or few of his priorities Congress decides to take on.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2G3o5CN

About the author

John Lovett – Merrimack College

John Lovett – Merrimack College

John Lovett is a Visiting Lecturer of Political Science at Merrimack College as of the fall of 2018, having most recently been a Visiting Lecturer of Political Science at the University of Richmond. His work primarily focuses on the interaction between members of Congress and the political media, and in particular how these interactions relate to public policy discourse.

I don’t know where you get your poll’s from but it’s not from rural areas. We love our (and your) President. Thanks for the great job President Donald Trump…