Despite the often loud rhetoric of those who are opposed to measures to mitigate climate change and sustainability in general, almost 65 percent of America’s large cities have put in place explicit sustainability initiatives. How and where sustainability is administered within a city’s bureaucracy is important as it can affect its functioning and performance. In new research which analyzes data from over 400 cities, Rachel M. Krause finds that sustainability administration and coordination is most often headquartered in public works or environmental services departments. The location of a city’s sustainability administration is not influenced by a city’s form of government or the support of local interest groups, but how city council members are elected can be important.

Despite the often loud rhetoric of those who are opposed to measures to mitigate climate change and sustainability in general, almost 65 percent of America’s large cities have put in place explicit sustainability initiatives. How and where sustainability is administered within a city’s bureaucracy is important as it can affect its functioning and performance. In new research which analyzes data from over 400 cities, Rachel M. Krause finds that sustainability administration and coordination is most often headquartered in public works or environmental services departments. The location of a city’s sustainability administration is not influenced by a city’s form of government or the support of local interest groups, but how city council members are elected can be important.

Sustainability – being a relatively new, cross-cutting, and at times even frustratingly comprehensive public objective – does not fit neatly into most governments’ existing administrative structures. With the stated ideal of achieving and balancing environmental, social, and economic well-being, sustainability functions can be – and indeed are – located all over the organizational map. This placement matters. Where a function is headquartered and how it is structured can shape bureaucratic priorities, processes, performance, and responsiveness. In new research, my colleagues and I analyzed over 400 cities to determine where sustainability administration is headquartered within city bureaucracy and why. We find that larger cities with a more mature commitment to sustainability are more likely to have dedicated units, but also that the form of local government and support of local interest groups seems to have little effect.

Over the past two decades, local governments have (somewhat surprisingly) emerged as policy leaders and innovators in sustainability and climate protection. In the United States, where federal legislation has languished, approximately 65 percent of cities with populations over 50,000 have explicit sustainability initiatives.

While it may be an exaggeration to say that each of these almost 450 cities utilizes a different structure to administer sustainability, considerable variation does exist between them. In some locales, sustainability is headquartered in the mayor or managers’ office and in others it is placed in one of several line departments. Some cities have specialized offices or divisions for sustainability management, whereas others have simply added it to an existing unit’s list of responsibilities. No structure or location has emerged as either the dominant or most effective administrative approach for the implementation of sustainability functions in local government.

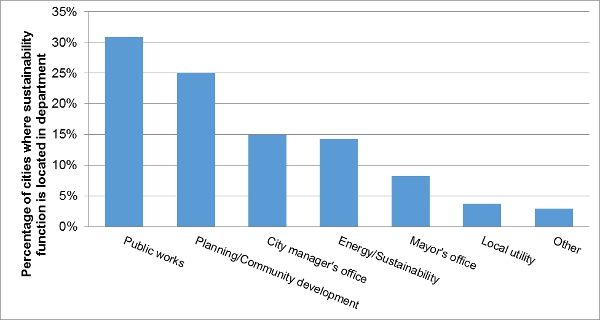

What patterns do exist? Among this sample of US cities, sustainability administration and coordination is most often headquartered in public works or environmental services departments. As Figure 1 illustrates, approximately 30 percent of cities have designated its primary responsibility to one of these units. Departments of planning or community development lead sustainability efforts in another 25 percent of cities. Sustainability is structured as an executive branch initiative approximately 23 percent of the time, with placement in the mayor’s or city manager’s office in 8 percent and 15 percent of cities, respectively. Municipally owned utilities direct local sustainability efforts approximately 4 percent of the time. Finally, about 15 percent of cities have created an independent office or department of sustainability that is not a sub-unit of any other department. This arrangement often reflects the highest level of local support and prioritization.

Figure 1 – Distribution of where US cities headquarter sustainability initiatives

The consequences of these administrative arrangements are meaningful and carry implicit programmatic emphasis or bias. However, a lack of systematic understanding about them leads to assignments that often appear to be made based on managerial personalities or budgetary conveniences rather than as part of a larger strategic plan.

What factors explain the variation in the placement of primary responsibility for sustainability in local government? Results of a statistical analysis run on the 400+ cities suggest that those with mature commitments to sustainability, larger overall populations and more resources are more likely to have specialized sustainability units that are either independent or headquartered in the executive. This conforms to expectation. More surprising is the lack of consistent impact that either form of government or the support of local interest groups has on placement. Also interesting is the significant and rather large effect that the make-up of city council – whether members are elected by district or at-large – has on how sustainability is structured. With every additional council member that is elected by district, the likelihood that a city has a specialized sustainability unit increases. Considering the known incentives of district-based representatives, this result may suggest that local sustainability efforts have distributive characteristics and generate project-based benefits that are specifically and geographically felt.

The logical next step for research on sustainability is to systematically assess the impact that administrative arrangements have on the types of actions pursued and their likelihood of success. Thus far, assumptions about the implications of placement are based on theory or anecdotes and have not been empirically evaluated. For example, theory suggests that sustainability efforts located in the executive branch, particularly a mayor’s office may be more responsive to community needs (or, from a less charitable perspective, they may be more susceptible to political pressures). The degree to which this plays out in practice is unclear.

A second example comes from discussions with sustainability coordinators who offer conflicting perspectives about their placement in terms of facilitating buy-in from other city departments. Some state that having direct administrative ties to the chief executive raises the issue of sustainability in the city hierarchy and results in better cooperation from line departments because it is seen as a directive from “the boss”. The experience of others, however, leads them to assert that sustainability initiatives are more successful when they are integrated into departments rather than being seen as coming from above.

These ideas and anecdotes are not enough to draw generalizable conclusions about the effect of sustainability’s administrative structure on outcomes. It is well known that organization can shape policy priorities and implementation, but how that occurs with city sustainability is not well understood. Research is underway to evaluate these implications and at some point in the (near) future, we expect to have developed a systematic and empirically-based menu of effective administrative arrangements that can be matched with specific combinations of community needs, capacities, and priorities.

This article is based on the paper ‘The Administrative Organization of Sustainability Within Local Government’, in the Journal of Public Administration Research.

Featured image credit: edibleoffice (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1wslumh

_________________________________

Rachel M. Krause – University of Kansas

Rachel M. Krause – University of Kansas

Rachel M. Krause is an assistant professor at the University of Kansas’s School of Public Affairs and Administration. Her research focuses on municipal climate protection, urban sustainability, and the adoption and diffusion of innovative environmental policies and technologies. She is involved in the development of the Integrated City Sustainability Database (ICSD) and authored the article “The Administrative Organization of Sustainability within Local Government” with Richard Feiock and Christopher Hawkins, which is published in the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory.

Very interesting research and findings. We notice the growing discrepancy between national and local governments when visiting places for the Sustainability Leaders project (http://sustainability-leaders.com).

The main issue is that the concept of sustainability doesn’t fit any functional unit or specific department within local administration. Lord Mayor’s office is perhaps the best place to watch over sustainability as a meta strategy. Sustainability comprises many different aspects, which need to be managed from the very top of the organization.