Over the past decade, same-sex marriage has grown in acceptance, and is now legal in 35 U.S. states. But how favorable are Americans towards same-sex couples? In new research that examines attitudes towards formal rights and informal privileges for same-sex couples, Long Doan, Lisa R. Miller, and Annalise Loehr find that while most Americans are supportive of same-sex couples having partnership benefits such as family leave and inheritance rights, this support does not extend to more informal privileges such as public displays of affection. They also find that many of those who support partnership rights for same-sex couples do not support their right to be married.

Over the past decade, same-sex marriage has grown in acceptance, and is now legal in 35 U.S. states. But how favorable are Americans towards same-sex couples? In new research that examines attitudes towards formal rights and informal privileges for same-sex couples, Long Doan, Lisa R. Miller, and Annalise Loehr find that while most Americans are supportive of same-sex couples having partnership benefits such as family leave and inheritance rights, this support does not extend to more informal privileges such as public displays of affection. They also find that many of those who support partnership rights for same-sex couples do not support their right to be married.

Americans’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays have become increasingly favorable over the past few decades. These and other related claims are based on research that has largely focused on issues of civil rights and legal protections for lesbians and gays, but what about Americans’ attitudes toward non-legal issues? In new research using nationally representative data, we make the distinction between views toward these more legalistic issues, which we call formal rights, and views toward more subtle, everyday interactions with lesbians and gays, which we call informal privileges. Our data show that Americans often have conflicting views toward formal rights and informal privileges. In fact, these conflicting attitudes are key to understanding how Americans view issues like same-sex marriage.

In our study, we provide participants with one of three stories describing an unmarried heterosexual, gay, or lesbian couple that has been in a relationship for about three years and has lived together for about two years. Key to the study design is that the couple is described in the exact same way with the only differentiating factor among them being their sexual identity, which we signal using their names. After reading the story, participants are asked to answer a series of questions about their views toward partnership benefits for the couple (part of the formal rights concept), their views toward the couple expressing affection in public (part of the informal privileges concept), and their views toward the couple getting married. In the study, we oversample lesbian and gay participants so that we can more reliably examine their views as well. All the items are measured on a one to four scale where one is strong disapproval and four is strong approval.

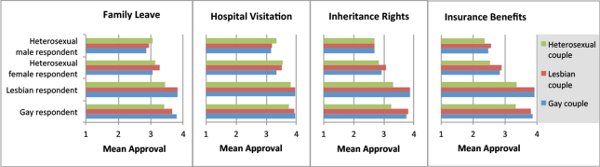

Figure 1 – Mean Approval of Formal Rights Items by Respondents’ Sexual Identity and Sex

Note: 1 = Low level of approval, 4= High level of approval.

Figure 1 shows average responses for each of the formal rights items broken down for heterosexual males, heterosexual females, lesbians, and gays. The green bar represents participants’ views toward the heterosexual couple, the red bar represents their views toward the lesbian couple, and the blue bar represents their views toward the gay couple. For both heterosexual males and females, the three bars do not differ much from each other, meaning that heterosexuals on the whole are equally as supportive of formal rights for the heterosexual couple as they are for the lesbian and gay couple. Sometimes, like with heterosexual females’ views toward insurance benefits for the lesbian couple, they are even more supportive of formal rights for the same-sex couple than for the heterosexual couple. Importantly, the study includes a heterosexual comparison group so that we can contextualize the relative support for formal rights for same-sex couples.

Lesbians and gays differ quite a bit from their heterosexual counterparts on these items. Not surprisingly, lesbians and gays are significantly more supportive of all of the formal rights items for the same-sex couples than for the heterosexual couple. Interestingly, they are also more supportive of formal rights for the heterosexual couple than even heterosexuals are. In other words, lesbians and gays are more supportive of formal rights for all couples, but especially for same-sex couples. We will return to this finding when we discuss views toward marriage.

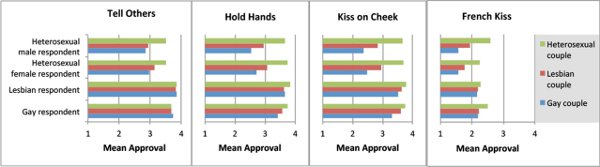

Figure 2 shows average responses for the informal privileges items. Despite having egalitarian views toward formal rights, heterosexuals are significantly less approving of same-sex public displays of affection (PDA) than of heterosexual PDA. This includes minor displays like the partners telling other people that they are a couple to more risqué displays like French kissing in public. Note that the approval drops substantially for French kissing across the board compared to other items – that is where people seem to draw the line for acceptability for all couples. However, even in that case, there is significantly more approval for the heterosexual couple French kissing in public than either same-sex couple.

Figure 2 – Mean Approval of Informal Privileges Items by Respondents’ Sexual Identity and Sex

Note: 1 = Low level of approval, 4= High level of approval.

Somewhat surprising to us is that gays and lesbians are sometimes less supportive of the same-sex couples’ PDA compared to that of the heterosexual couple. We suspect that this is because they are keenly aware of the verbal harassment and violence that may result if lesbian and gay couples express affection in public. Part of the reason for this interpretation is that unlike heterosexuals, who are disapproving across the board of informal privileges, lesbians and gays are only less approving of the visible PDA items, like holding hands and kissing in public, not of telling people they are a couple. This suggests caution rather than internalized prejudice to us.

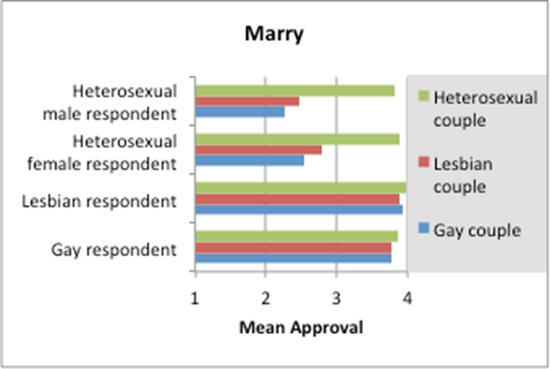

Figure 3 shows average responses for the couple getting married. The interesting pattern here is that it looks a lot like the graphs for the informal privileges items even though most people think of marriage as a formal, legal right. Heterosexuals are significantly less approving of the same-sex couple getting married compared to the heterosexual couple. Although heterosexuals indicate a preference for equality in terms of formal rights, somewhat paradoxically, they are relatively opposed to the very policy that would grant same-sex couples these formal rights. Past research, especially research on racial inequality, calls this the “principle-implementation gap,” where people support equality in principle, but they do not support the implementation of the policy that leads to the realization of that principle. Indeed, heterosexuals do not seem to be thinking of marriage in terms of rights, but instead in more symbolic, informal terms.

Figure 3 – Mean Approval of Marriage by Respondents’ Sexual Orientation and Sex

Note: 1 = Low level of approval, 4= High level of approval.

The patterns for lesbians and gays are also interesting. Earlier, we mentioned that lesbians and gays were significantly more approving of formal rights for same-sex couples than for heterosexual couples. Despite this, they are equally (and almost universally) as supportive of marriage for all couples. Together, these findings suggest that lesbians and gays think that everyone should be able to get married, but because same-sex marriage is still not available everywhere in the U.S., same-sex couples should have the partnership benefits that come with marriage instead.

Our findings raise important questions about how we tend to gauge equality. Scholars, the public, and the mainstream gay movement alike have had a tendency to think that the arrival of marriage and legal rights will result in sexual minorities finally reaching equality. Yet, our findings again show that support of legal rights is not the same thing as complete acceptance of lesbians and gays, and Americans often hold conflicting views toward same-sex couples. This suggests that the public needs to be having a broader conversation about what equality would look like in practice.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Formal Rights and Informal Privileges for Same-Sex Couples: Evidence from a National Survey Experiment’, in the American Sociological Review.

Featured image credit: Guillaume Paumier (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1DppV9x

_________________________________

Long Doan – Indiana University

Long Doan – Indiana University

Long Doan is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at Indiana University. He is broadly interested in how emotions motivate behavior and maintain inequality. His current projects examine (1) the role of emotional attributions in explaining differences in heterosexuals’ willingness to grant formal rights and informal privileges to same-sex couples and (2) how emotions and power affect third-party interventions in conflict.

Lisa R. Miller – Indiana University

Lisa R. Miller – Indiana University

Lisa R. Miller is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at Indiana University. She specializes in the sociology of gender, sexualities, social psychology, and race/class/gender. Her research in these areas specifically investigates the nature and consequences of prejudice and discrimination against LGBTQ individuals. Lisa’s dissertation research examines how women navigate dating and sexual partnerships throughout the life course.

Annalise Loehr – Indiana University

Annalise Loehr – Indiana University

Annalise Loehr is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at Indiana University. Her primary areas of interest include social psychology, gender, sexualities, deviance, and the scholarship of teaching and learning. Current research projects examine prejudice against gay and lesbian couples. One such project considers whether contact facilitates more positive attitudes toward same-sex couples, even when controlling for possible selection bias.