When disaster strikes, governments tend to be held accountable whether it is an economic disaster, such as the recent financial crisis, or a terrorist attack. In new research, Ryan E. Carlin, Gregory J. Love and Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo use data from Latin America to examine the effects of unified and divided government on how citizens ascribe blame when terrorism and negative economic outcomes occur. They find that because the executive shares responsibility with national and international factors for the state of the economy, citizens are more forgiving when government is divided. After terrorist attacks, on the other hand, citizens blame their leaders even if government is divided as they see their leaders as having near sole responsibility for issues of national security.

When disaster strikes, governments tend to be held accountable whether it is an economic disaster, such as the recent financial crisis, or a terrorist attack. In new research, Ryan E. Carlin, Gregory J. Love and Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo use data from Latin America to examine the effects of unified and divided government on how citizens ascribe blame when terrorism and negative economic outcomes occur. They find that because the executive shares responsibility with national and international factors for the state of the economy, citizens are more forgiving when government is divided. After terrorist attacks, on the other hand, citizens blame their leaders even if government is divided as they see their leaders as having near sole responsibility for issues of national security.

The recent terrorist attacks in Paris—as well as high-profile terrorist attacks in other democratic countries, including Argentina, Spain, the U.S., and India—raise important questions about the causes of terrorism and about how it can be prevented in the context of democratic politics. The attacks and the protests that have followed them also raise the question of whether leaders in democratic systems are likely to suffer political consequences—including the potential of being kicked out of office—for what citizens perceive as substantial security failures.

Much of what we know about how the public metes out blame or credit for policy outcomes comes from the field of political economy. One of the most common hypotheses in this field states that the public is more likely to hold leaders accountable for economic performance when “clarity of responsibility” is high. Under unified government (when one party controls both the executive and the legislature), for example, citizens will be more likely to blame or credit the executive (president, prime minister, etc.) for economic policy, which they see as reflecting the executive’s vision and priorities. The perception that the economy’s fate rests in the executive’s hands makes it difficult for leaders to shift blame for failures but easy to take credit for successes. In such circumstances, when the economy roars leaders ride a wave of popularity. But when it tanks so does their public approval.

If unified government illuminates who is responsible for economic performance, divided government obscures it. When the opposition controls the legislature, economic policy must bear both the opposition’s and the government’s stamp of approval. The perception that political actors share responsibility for crafting economic policy makes citizens less likely to think executives are solely responsible for the economy – and less likely to credit or blame executive leaders for economic outcomes – under divided government.

Although this hypothesis has a good track record of explaining patterns of accountability for economic outcomes, it does not explain when citizens will hold executives accountable for terrorism and security outcomes. In our recent research, we argue that there are two central reasons for this: first, there are important differences in who citizens perceive to be responsible for economic and national security outcomes. Second, security and economic policy failures present different opportunities for executives to create a narrative frame that benefits them. We explain each of these reasons below.

First, in most countries executives share responsibility for economic policy with other domestic and international political actors — and citizens know this and take it into account when assigning credit or blame for economic outcomes. But citizens, and most constitutions, place responsibility for terrorism and national security squarely on the shoulders of the executive. This makes it hard for leaders to shift blame for security breakdowns. Claiming that their hands were tied strains credulity. In addition, security failures create a bully pulpit from which the opposition can roundly criticize the executive and, since they share no responsibility, gives them a cheap way to score political points.

Second, although it is extremely difficult to put a positive spin on economic crises, security policy failures produce different options for executives. Under unified government, sitting executives can blame the violence on the attackers rather than on their government’s failure to prevent the attack. Threatening and evocative media coverage reinforces this frame and helps executives rally the public to their side and in support of their policy response. Thus, while unified government makes it more likely that the executive will get blamed for economic failures, it makes it less likely that terrorism and security crises will hurt executives’ public support.

Under divided government, by contrast, opposition leaders have enough resources at their disposal – speakerships, committee chairmanships, better access to the media, etc. – to allow them to counter-frame and, thus, challenge the executive’s narrative. This back and forth hurts the ability of the executive to impose its preferred narrative. As a result, when it comes to security and terrorism, divided government makes it more likely that citizens will blame the executive for a policy failure or crisis.

When it comes to terrorism and security policy, then, the classic “clarity of responsibility” hypothesis, developed to explain accountability for economic outcomes, seems to function in reverse. The contrast between presidents Alan Garcia of Peru and Alvaro Uribe of Colombia provides a good example. In mid-2007 García was faced with withering criticism from Peruvian opposition leaders in Congress and a 7.1 percentage point drop in approval following a Sendero Luminoso (a Maoist guerrilla group) attack that killed 60 people. In contrast, Uribe enjoyed a united government that allowed him to shape the narrative more easily and to escape blame following attacks that killed or wounded 196 people in 2002.

To explore this idea empirically, in our research we look at how acts of terrorism influence executive support in 18 Latin American democracies in the context of either unified or divided government. We use historical data that covers the period from 1980 to 2007. For terrorism casualties we use data from START’s Global Terrorism Database; data on clarity of responsibility come from Witold Henisz’s Political Constraints Database; presidential approval data come from our own Executive Approval Database; economic data are taken from the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean’s CEPALSTAT; and controls for level of democracy are from the Center for Systemic Peace’s Polity IV Project. If our argument is correct, terrorist attacks should reduce presidential approval less under unified government than under divided government.

This is exactly what we observe.

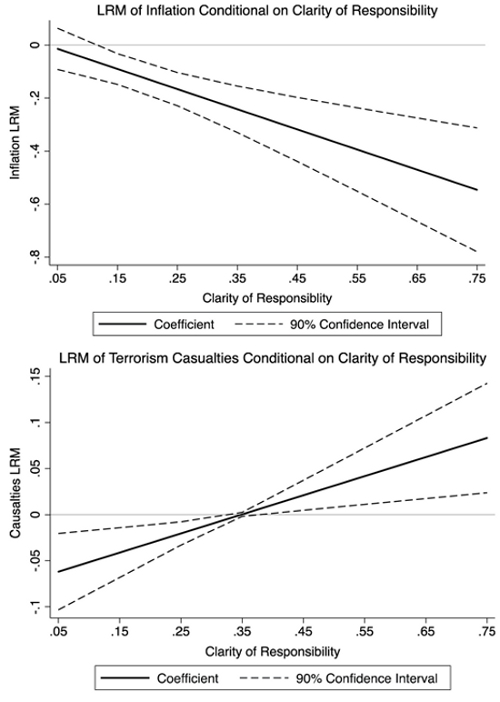

Figure 1 – The Effects of Inflation and Terrorism on Presidential Approval Conditional on Clarity of Responsibility.

Note: LRM= long run multiplier. Source: Carlin, Love & Martinez-Gallardo forthcoming.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between inflation (top panel) and casualties attributed to terrorism (bottom panel) and presidential approval at different levels of clarity of responsibility (or the degree to which government authority is divided). The Figure highlights our main finding: while presidents facing an opposition congress (low clarity of responsibility) can somewhat avoid blame for a failing economy, executives under the same circumstances are likely to be punished for security failures. In other words, the consequences of an economic crisis for executives’ approval are worse under divided government, when voters have a hard time deciding whom to blame for policy outcomes. In contrast, security crises are more likely to dent executives’ approval when the government is unified because they cannot credibly shift blame.

The conditionality of accountability we examine in this research and in a previous paper focused on political scandals, highlights the challenges involved in understanding democratic accountability. Our work suggests it is important to look not only at the political environment – whether the government is unified or divided—but also at the nature of the particular policy issue. By taking both factors into account, performance accountability can be viewed as a complex relationship between issue ownership, blame shifting, and the effectiveness of executive and opposition narratives. In particular, the issue ownership executives have over security policy is clearly a blessing and a curse. Executives can often feel emboldened and less constrained by the legislature when dealing with matters of national security and physical safety. However, when a country suffers a security failure, executives find it hard to shift blame onto an opposition legislature, and instead face vocal criticisms that tend to lower their public support.

This article is based on the paper ‘Security, Clarity of Responsibility, and Presidential Approval’, in Comparative Political Studies.

Featured image credit: J E Theriot (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1xy0Scr

_________________________________

Ryan E. Carlin – Georgia State University

Ryan E. Carlin – Georgia State University

Ryan Carlin is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Georgia State University. His main research field is comparative political behavior, especially in Latin America. His other research interests include natural disaster politics, social preferences, rule of law, and political institutions.

_

Gregory J. Love – University of Mississippi

Gregory J. Love – University of Mississippi

Greg Love is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Mississippi. He specializes in the politics of Latin America and developing countries broadly. One of his specific research interests is how political careers develop and change in transitional democracies and how these changes affect the quality of governance. He has conducted extensive field research in Mexico and Chile for this and other projects.

_

Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Cecilia Martinez-Gallardo is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her teaching and research interest are in Latin American political institutions, especially government formation and change. Her work focuses on the political and institutional factors that affect coalition politics in these countries. She has also worked on government formation and stability in Western Europe and as well as policy reform in Latin America.